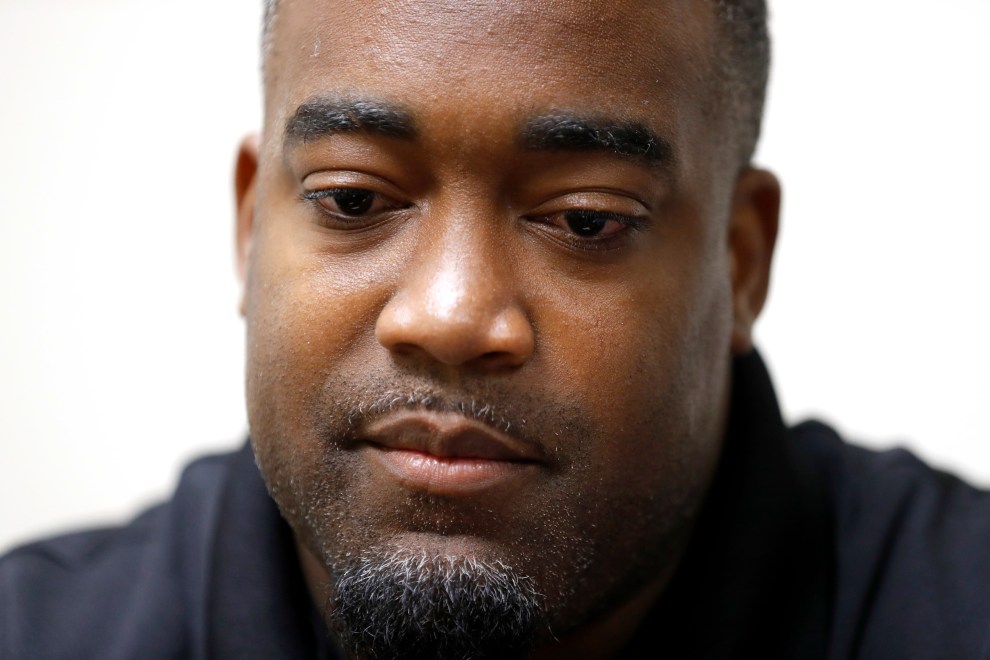

Dallas Police falsely labeled Mark Hughes, a legal gun carrier, as a cop-killer suspect.Eric Gay/AP Photo

Millions of Americans watched Philando Castile die in his car. The 32-year-old was driving in a Minneapolis suburb last July with his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, and Dae’Anna, their four-year-old daughter, when they were pulled over for a broken taillight. Castile told the officer that he had a legally permitted firearm, but when he reached for his wallet, his girlfriend said, the officer panicked and opened fire. Demonstrating remarkable composure, Reynolds livestreamed the aftermath on Facebook, capturing Castile’s final moments, as the cop screamed, “I told him not to reach for it! I told him to get his head up!”

“He had!” Reynolds countered. “You told him to get his ID, sir. His driver’s license. Oh my God, please don’t tell me he’s dead!”

Castile was just one in a long line of black gun owners to be misconstrued as a deadly threat. From fatal to merely inconvenient, the incidents are telling: Clarence Daniels walked into a Florida Walmart only to be tackled by a white Samaritan who’d spotted the holstered (and legally permitted) gun under Daniels’ jacket and assumed he was up to no good. Alton Sterling was shot dead by Baton Rouge, Louisiana, police while pinned facedown on the pavement, his gun in his pocket. Mark Hughes openly carried his rifle, as Texas law allows, to a Dallas Black Lives Matter protest the day after Castile’s death. When a sniper at the demo started shooting cops, Dallas Police tweeted out Hughes’ photo, falsely naming him as a suspect. Death threats followed. And Hughes faced a hostile interrogation after he dutifully handed over his weapon.

Prior to the ’90s, concealed handgun permits were doled out sparingly—14 states banned them entirely. But thanks to the National Rifle Association—which relentlessly hawks the notion that a good citizen is an Armed Citizen—all 50 states now offer a pathway to concealed carry. Permits ballooned from 1 million in 1990 to more than 13 million in 2014, and 12 states have adopted “constitutional carry” policies, which allow people to pack heat without any kind of permit or safety training. New Hampshire joined that club recently. On Friday, President Donald Trump addressed the NRA’s annual convention, declaring that the “eight-year assault” on gun ownership had come to a “crashing end”—a laughable statement, given that gunmakers enjoyed a historic boom under President Barack Obama but have seen sales slump since Trump was elected.

The right to self-defense has become similarly sacrosanct, fueling the spread of Stand Your Ground laws to more than half the states. First passed in 2005 in Florida, these laws allow us to use lethal self-defense without retreating, wherever we feel threatened. (Read Mother Jones‘ 2012 story on how the NRA and its allies helped spread the idea.) The Florida Legislature may be on the brink of passing a law that could be described as Stand Your Ground on steroids: SB 128 would shift the burden of proof in pretrial immunity hearings so that prosecutors have to disprove a defendant’s self-defense claim beyond a reasonable doubt before a case can go to trial. (Normally, a defendant has to present pretrial evidence to convince a judge that the self-defense claim is warranted.)

In addition to encouraging more violent-crime defendants to claim self-defense, Florida’s “fix” would make it significantly easier for certain people to get away with murder—and therein lies the catch. Because while all the laws that govern gun rights and self-defense are equitable on their face, statistics and everyday experience tell a different story: that a black man (or boy) who carries a gun (or almost anything that might be mistaken for one) faces a disproportionate risk of being viewed as a criminal threat. In 2014, Cleveland police gunned down Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old with a toy pistol who was sitting by himself in a park, threatening nobody—the officer who shot him walked.

Over the past two years, the Washington Post has amassed a database of deadly shootings by police officers. Last year’s numbers, adjusted for population, show that black men were three times more likely than white men to be killed by police. Academic researchers who independently vetted the Post’s data concluded that “police exhibit shooter bias by falsely perceiving blacks to be a greater threat than non-blacks.”

For a study out in March, psychologists showed facial photos of young black men and young white men to 951 study participants. The black men were consistently judged to be bigger and stronger than the white men, even though all were roughly the same size. In addition, nonblack participants in the study judged the black men as “more capable of causing harm in a hypothetical altercation and, troublingly, [believed] that police would be more justified in using force to subdue them, even if the men were unarmed,” explained the study’s lead author, Montclair State University researcher John Paul Wilson. Darker-skinned men and those with more stereotypically black features “tended to be most likely to elicit biased size perceptions,” he added.

Similar biases are evident in the spread of the Stand Your Ground laws. According to a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, gun-related homicides in Florida have increased by 32 percent since its law was enacted. When the Urban Institute‘s John Roman crunched FBI stats from 2005 through 2010, he found that white-on-black homicides in SYG states were 11 times more likely to be ruled justified than black-on-white homicides. “Even with no racial animus, the black/crime association remains,” Stanford psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt told the American Bar Association’s National Task Force on Stand Your Ground Laws (whose report is well worth reading). “It creeps in, infecting how we see the world, how we act upon it.”

Our biases enter the equation long before a case reaches the courtroom. SYG laws offer protection to killers who “reasonably” claim to have acted in self-defense, but what’s reasonable is a highly subjective determination—George Zimmerman wasn’t arrested and charged until weeks after he’d killed Trayvon Martin in Florida. To some observers, a pair of roadside homicides in Louisiana last year underscored the racial double standard: Police took four days to arrest a white man with a history of road-rage violence who’d fatally shot former NFL player Joe McKnight. Yet the black suspect in the road-rage killing of another pro footballer, Will Smith, was taken into custody right away. Both men had claimed self-defense.

None of the above should come as a surprise, given our nation’s tortured history. Consider District of Columbia v. Heller, the 2008 Supreme Court case that affirmed an individual’s right to “keep and carry weapons in case of confrontation.” The late Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, relied on his “originalist” interpretation of the Second Amendment, ignoring the fact that in 1791, when the amendment was adopted, the term “law-abiding citizen” applied to white, property-owning men who carried rifles not just to defend “hearth and home,” but to assert their dominance over enslaved labor and land seized from Native people.

After slavery was formally abolished in 1865, whites resisted by trapping free blacks into criminality. Ava DuVernay’s remarkable documentary, 13th, shows how that amendment’s ban on “involuntary servitude” exempted “punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Vagrancy laws criminalized blacks who could not prove “lawful employment” and, well into the 20th century, black Americans were imprisoned for minor infractions, like spitting on the sidewalk, and forced to labor indefinitely under inhumane conditions. (African Americans are nearly six times as likely to be locked up as whites.)

The so-called Black Codes also prohibited black people from defending themselves against white supremacist violence. Mississippi’s Penal Code stipulated that “no freedman…not in the military service of the United States government…shall keep or carry firearms of any kind.”

States eventually purged the explicitly racist laws from their books, but the discrimination continued. In 1927, for example, Michigan gave counties sole discretion in the issuance of firearms permits—a means of reducing black gun ownership in heavily black counties. The legislation was inspired by the previous year’s acquittal of Ossian Sweet, a black physician who had used firearms to protect his home and family from a white mob that tried to drive them out of a white Detroit neighborhood.

In 1967, after Black Panther Party members began carrying rifles openly in public, California Gov. Ronald Reagan (with the NRA’s blessing) signed a repeal of the state’s open-carry law, insisting the rollback “would work no hardship on the honest citizen.” In 1968, the federal Gun Control Act updated a 1934 law by prohibiting all former felons, not just those convicted of violent crimes, from owning and bearing arms.

The criminalization of black men has also hinged on pernicious fallacies about their uncontrolled desires for white women, lies that were used to justify what the Equal Justice Initiative calls “racial terror” and the lynching of an estimated 4,000 black people. Newspapers in the postbellum South regaled readers with stories of “Negro Rapists” and “Lustful Brutes,” guilty of heinous crimes against white femininity—never mind that black women and girls had far more to fear from white men.

As I argue in my new book about the history of lethal self-defense, the myth that white women need protection against dark strangers remains lodged in our national psyche, allowing contemporary supporters of gun carry and Stand Your Ground laws to invoke racial fears without ever mentioning race. Indeed, a recent study found that the most vocal supporters of gun rights tended to imagine criminals as black, while envisioning “law-abiding” citizens as white.

The fear of a black stranger helps the NRA peddle its Refuse to be a Victim seminars, yet the self-defense laws the group champions were never designed to protect women against violent husbands and boyfriends—even though, according to the Violence Policy Center, nearly two-thirds of the women slain by men in 2013 were intimately involved with their killers. And the nonprofit Correctional Association of New York found that two-thirds of the women imprisoned in 2005 for killing someone close to them were abused by the person they killed. “Most battered women who kill in self-defense end up in prison,” Rita Smith, the executive director of the National Coalition on Domestic Violence, noted in 2013. “There is a well-documented bias against women [in these cases].”

The NRA doesn’t disclose its ethnic breakdown, but when Detroit firearms instructor Rick Ector, who is seeking to join the group’s board of directors, attended the group’s 2012 conference in St. Louis, he spotted only 12 other black people in a gathering of more than 70,000. “I may have missed a few but not many,” he wrote on Ammoland.

And what to make of the NRA’s silence when black gun owners are harassed or killed for exercising their Second Amendment rights? Within hours of five cops being slain in Dallas, CEO Wayne LaPierre released a statement expressing the “deep anguish all of us feel for the heroic” police officers, but he offered no support for Hughes, the black gun owner misidentified as a cop-killer. In the wake of the back-to-back killings of Sterling and Castile that week, the NRA had no comment. Only amid criticism from its own members, two days after Castile’s death, did America’s most powerful gun rights group concede that “the reports from Minnesota are troubling.”

Yes, troubling indeed.