Jeff Chiu/AP; Mikolajn/Getty

The low-profile prosecution of a 22-year-old Canadian hacker may offer clues regarding how US intelligence officials learned about Russia’s efforts to disrupt last year’s election—and it could offer a lot more clues if the case goes to trial.

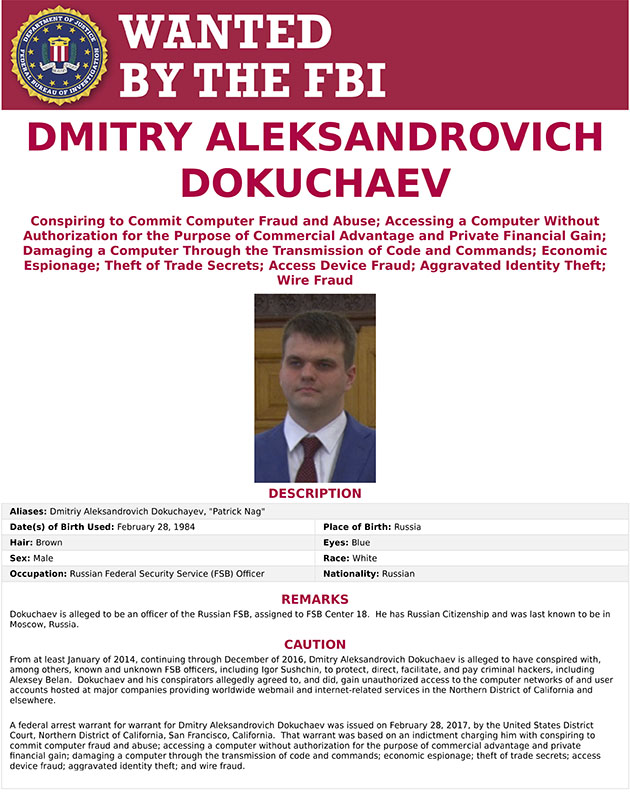

Last month in US District Court in San Francisco, Karim Baratov, a Canadian citizen born in Kazakhstan, pleaded not guilty to multiple felonies related to his bit part in the cyberattack that compromised 500 million Yahoo accounts starting in 2014—and that nearly derailed Yahoo’s acquisition by Verizon. Of the four men indicted, Baratov is the only one in US custody. The others include an internationally wanted Latvian hacker and two members of a cyber unit within Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB for short). They are the first FSB operatives American authorities have charged in any hacking case.

One of the FSB guys, Dmitry Dokuchaev, is part of a group of Russian intelligence officials reportedly jailed in Russia last December for treason. According to Russian media reports, Dokuchaev and an FSB superior, Sergei Mikhailov, stand accused of passing information about Russia’s election hacking to US intelligence agencies. The Russian news service Interfax reported that the two men were “accused of breaking their oath and working with the CIA.”

Another publication, Novaya Gazeta, reported that Russian authorities believe Mikhailov alerted American officials to the role of a server-rental firm called “King Servers,” which US cybersecurity sleuths say was used by the Russian hackers suspected of penetrating election systems in Arizona and Illinois in 2016 and voting systems in Germany, Turkey and Ukraine.

While these reports, attributed to unnamed officials, might be disinformation, the February Yahoo indictment suggests, as some cyber experts have speculated, that Dokuchaev was indeed a double agent. This is because the indictment details communications between Dokuchaev and Igor Sushchin, the more senior FSB official charged in the Yahoo case—a possible indication that Dokuchaev provided information to the United States. It also contains extensive information about Dokuchaev’s interactions with the hackers charged with assisting the FSB in the Yahoo attack. That may be another sign Dokuchaev was in contact with US intelligence. The fact that he was indicted in the United States might be read to mean he was not a US intelligence asset—would the government indict an overseas spy it had recruited? But a former Justice Department official notes it would be a logical for the feds to do just that in order to provide cover.

If Dokuchaev was a double agent, he may have supplied the CIA with far more information about Russian hacking than has come to light in the Yahoo case. According to David Hickton, a former US attorney who oversaw a case in which members of the Chinese military were indicted for hacking American corporations, it’s a “reasonable assumption” that the information revealed in the indictment is the tip of the iceberg. “You can assume there is more to this,” Hickton said. “This is a very important case.”

In a January 2017 report, US intelligence agencies, without naming their sources, concluded with “high confidence” that Russian President Vladimir Putin had “ordered an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at the US presidential election” that included an effort “to denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency” while benefiting Trump. The apparent penetration of the FSB’s cyber unit by American intelligence may have contributed to the agencies’ conclusions. (Russia’s arrests of Dokuchaev and Mikhailov were part of a larger purge, suggesting that US intelligence may have had sources deep inside Russia’s cybersecurity unit.)

“The Russians are almost certainly right that Dokuchaev provided sensitive information to the Americans,” says Dave Aitel, a former NSA employee and head of Immunity, a computer security company. “You can’t assume it was election-related, but it’s possible.”

In addition, cybersecurity analysts have concluded that the FSB used freelance hackers to influence the US presidential election. The most notable Russian hacking group was Cozy Bear (a.k.a. APT 29), one of the shadowy groups accused of mounting intrusions into the Democratic National Committee, the White House, the State Department, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Any FSB personnel compromised by US intelligence might have information on the agency’s myriad hacking activities, Aitel says. “The FSB isn’t that big.”

Baratov, one of the accused Yahoo hackers, was extradited to the Unites States last month to be prosecuted. With discovery underway, prosecutors are obligated to share their evidence with the defense. But District Court Judge Vince Chhabria has signed an order barring attorneys from releasing any pretrial materials that prosecutors deem sensitive due to privacy or national security concerns.

But if Baratov ends up standing trial, the prosecutors may have to reveal in open court how they built their case—and whether they relied on information from Dokuchaev. If the case does reach, much of this sensitive information “should be public,” says Andrew Mancilla, an attorney representing Baratov. Neither the Justice Department nor the US attorney’s office prosecuting the case responded to requests for comment.

The Yahoo indictment does not address election-hacking directly. But it does indicate that US officials have detailed knowledge of activities of Russians who may also have been involved in election-related efforts. The document asserts that Dokuchaev, working under Sushchin and other unnamed FSB officials, oversaw a scheme in which the Latvian hacker named in the case—Alexsey Belan, known in the cyber world as “Magg”—stole information from at least 500 million Yahoo users.

With this data, prosecutors charge, the conspirators accessed other email accounts of people the FSB wanted to spy on, including American and Russian officials, Russian journalists, a Russian cybersecurity firm, and executives in the finance, transportation, and technology industries. The targets included two American cloud-computing firms. Belan also allegedly profited by searching the stolen Yahoo accounts for credit and gift-card information and by manipulating Yahoo search traffic to score commissions from a company that sold erectile dysfunction products.

Baratov, the Canadian, is charged with a smaller role. The indictment says Dokuchaev sent him data from the Yahoo hack—which Baratov is not accused of participating in directly—to help him break into more than 80 additional email accounts belonging to FSB targets. Dokuchaev allegedly paid Baratov $100 per account.

Dokuchaev is central to the scheme described in the Yahoo indictment. He reported to Sushchin and oversaw Belan and Baratov. The indictment describes two email exchanges in which Dokuchaev sent Sushchin “a minted cookie”—a small file with information about a specific account—along with instructions on how to break into that account.

Overall, experts say, the Yahoo case provides an unusually detailed look at how Russian intelligence officials interact with freelance hackers. These relationships help Russian intelligence maintain a level of deniability and enhance their capabilities. “It’s a really interesting picture of how the whole system is put together,” Aitel remarks.

The Kremlin, not surprisingly, denies any connection to the Yahoo case. In March, Russian spokesman Dmitri Peskov declared, “We have repeatedly stated that there can be absolutely no question of any official agency, including the FSB, in any unlawful actions in cyberspace.”