Larry Marano/Rex Shutterstock/ZUMA

You’ve likely heard by about the Uranium One story—a much-hyped Washington controversy promoted by conservatives, led by President Donald Trump, who are accusing Hillary Clinton of handing over US uranium to Russia as part of a pay-to-play scheme. At issue is the 2010 sale of a Canadian company called Uranium One, which had extensive holdings in the United States, to a Russian entity. The deal allowed a subsidiary of Russia’s government-owned Rosatom to gain control of 20 percent of US uranium—which is used for nuclear energy facilities, not nuclear weapons. Criticism of this transaction is not new, and it isn’t accurate, either. The high-volume complaints from the right have been repeatedly picked apart by fact checkers.

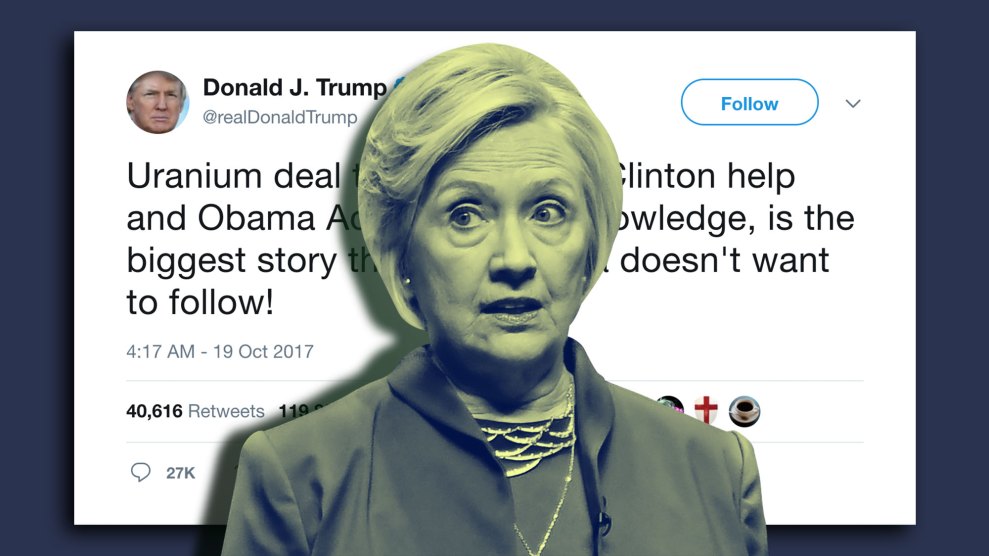

Still, the issue has been thrust onto the political-media landscape by conservatives and Republicans looking to distract from the Trump-Russia scandal. Republican-led committees in the House and Senate have loudly launched investigations of the deal. Trump called it a “modern age” Watergate. He tweeted about the case again over the weekend in what looked like an effort to draw attention away from impending indictments of his campaign staffers. Fox News has breathlessly covered the story in recent weeks, as if it were some new hot-scoop revelation. (It isn’t.) And Rush Limbaugh even speculated that “one of the objectives” of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russia’s covert intervention in the 2016 election “is to protect anybody and everybody that had anything to do with this Clinton-Obama-Russian uranium deal.”

Uranium deal to Russia, with Clinton help and Obama Administration knowledge, is the biggest story that Fake Media doesn't want to follow!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 19, 2017

None of this is accurate. The uranium story is based on a series of false claims and flawed assumptions. And it has been used by conservatives to convince the public that there is another Russia-related scandal offseting Mueller’s probe. But the conservative political-media machine will not be letting go of this anytime soon. So here’s what you should know about the Uranium One story.

Where does the Uranium One story come from?

Two words: Steve Bannon. In 2012, Bannon and Peter Schweizer, a conservative author, established a tax-exempt nonprofit organization called the Government Accountability Institute. They used funding from the family foundation of hedge funder manager and conservative mega-donor Robert Mercer. Bannon, of course, took over Trump’s presidential campaign in August 2016 and was ousted this summer from a post as a top White House aide. The institute was separate from but closely linked to Breitbart News, where Bannon and Schweizer also worked. Schweizer wrote a book, Clinton Cash, which portrayed Bill and Hillary Clinton’s charitable foundation as a corrupt scheme and cited the Uranium One deal as a primary example.

Schweizer’s biggest achievement was to get some of his claims into the the New York Times. The Times, eager to show it was serious about investigating Hillary Clinton, entered what it called an “exclusive” agreement to base a reporting project on Schweizer’s work. The result was an April 23, 2015, article headlined: “Cash Flowed to Clinton Foundation Amid Russian Uranium Deal.” According to the story, Schweizer “provided a preview of material in the book to The Times, which scrutinized his information and built upon it with its own reporting.”

What was the crux of the Times article?

The Times article reported that nine people linked to Uranium One—principally Frank Giustra, whose company Uranium One purchased in 2007, and Ian Telfer, a big investor in Uranium One—had made or pledged nearly $145 million worth of donations to the Clinton Foundation before a US government body approved the sale of Uranium One to the Rosatom subsidiary 2010. Clinton, as secretary of state, officially held a seat on this body, known as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). As a result of the deal, the Russian government-owned company now would control 20 percent of uranium production capacity within US borders. The article said the sale raised concerns about “American dependence on foreign uranium sources, since the United States imports most of the uranium it uses for nuclear power plants.”

So does that mean Hillary Clinton was bribed?

No. Neither Schweizer nor the Times offered any evidence suggesting the donations influenced Clinton. The reports actually contained ample evidence to the contrary. The Uranium One sale was unanimously approved by CFIUS, which is made up of representatives from nine separate federal agencies and chaired by the Treasury Department. The State Department was just one of the member agencies. By all accounts, Clinton’s role was nominal. In practice, Jose Fernandez, then the assistant secretary of state for economic, energy and business affairs, represented the State Department on CFIUS. He told the Times that Clinton “never intervened with me” on any matter the panel considered. It’s not even clear if Fernandez briefed Clinton about the uranium deal. And Giustra, the Clinton Foundation donor at the center of the Times story—who was responsible for $140 million of the $145 million in reported contributions—said he had sold his share of Uranium One three years before the Russian deal. Giustra said he never mentioned the deal to Clinton, whom he met at charity events. And why would he? He had no stake in it.

The 2010 approval, which allowed Rosatom to acquire a controlling stake in Uranium One, was actually one of two approvals the foreign investment committee gave related to Uranium One. In 2013, the panel okayed the Russian firm buying the remaining shares of Uranium One. That green light came after Clinton had left the State Department. This certainly undermines the suggestion that without Clinton’s supposed intervention, the original deal wouldn’t have been approved.

Perhaps more significantly, the sale had no evident effect on the availability of uranium within the United States. While the deal made Rosatom the owner of one-fifth of American uranium deposits, the company cannot export US-produced uranium without a license. Before and after the deal, a shipping company that worked with the firm and holds such a license shipped some of the uranium mined by Uranium One in the United States to Canada for processing. A Uranium One spokeswoman told the Times that most of that uranium returned to the United States for use in nuclear facilities, and 25 percent went to Western Europe and Japan. In other words, the company’s uranium continued to move under the same regulatory and market forces it had before the sale. It was not, and cannot be, handed over to the Kremlin, as Trump has suggested.

Does it matter if Russia owns a lot of US uranium?

Not really. The alarming coverage of sale seems to be based on confusion over how uranium is used. Uranium is a heavy metal that can be mined and enriched through an elaborate process to serve as fuel for nuclear power plants, which produce electricity. It requires far more enrichment to be usable for nuclear weapons. But neither the United States nor Russia needs more highly enriched uranium for bombs. Each country has more than 4,000 stockpiled nuclear warheads, more than enough firepower to destroy each other.

The United States, like Russia, also “already has all the highly enriched uranium we are ever going to need,” says Owen Cote, associate director of the Security Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. With a surplus of highly enriched uranium, both countries stopped making it in the 1960s, Cote notes. (Since 1993, the United States has also purchased highly enriched uranium from decommissioned Russian nuclear weapons as part of a nonproliferation effort. Those ongoing purchases are more significant for nuclear safety than the ownership of Uranium One.) It is not access to raw uranium that makes countries dangerous, but rather the technical capability to enrich it into weapons-grade material and build missiles capable of delivering warheads. “It really doesn’t matter where uranium comes from,” Cote said. “This does not seem like a national security issue.”

The uranium at stake in the deal does form a piece of the supply chain used to generate power in the United States. But critics of the sale have not offered any coherent arguments that the uranium could be diverted to Russia, or that such an outcome would even have any effect on America’s energy supply. In other words, CFIUS appears to have unanimously approved the Uranium One sale because there was no reason for it to object, not because of donations to the Clinton Foundation.

Didn’t this all come up during the campaign?

Yes. The Times report drew a detailed response from Clinton’s campaign, follow-up stories in other publications and fact-checks. And not surprisingly, it formed the basis of Trump campaign ads claiming Clinton handed uranium over to Russia. “Remember that Hillary Clinton gave Russia 20 percent of American uranium and, you know, she was paid a fortune,” Trump told supporters at an October 2016 rally, according to the Washington Post. “You know, they got a tremendous amount of money.”

So why is this story coming up again now?

The immediate reason the Uranium One story is back is a recent report in the Hill newspaper detailing the federal government’s investigation and subsequent conviction of Vadim Mikerin, an official with a different Rosatom subsidiary, for attempted payment of bribes and receipt of kickbacks in dealings with a US trucking company that transported uranium. The Hill story, shifting the focus from Clinton to the former Attorney General Eric Holder, who also sat on CFIUS, suggests that Holder and the Obama-era Department of Justice erred by failing to cite the Mikerin prosecution as a reason to block the Uranium One sale.

What’s wrong with this new account?

For one thing, it’s mostly not news. The case was reported on in major publications as the Justice Department publicly prosecuted and convicted Mikerin in 2015. The Hill bizarrely accuses the Justice Department of treating the case with a “lack of fanfare,” despite the department issuing press releases announcing the charges against Mikerin, his plea deal, and his sentencing. The story asserts the case was part of an effort “to grow Vladimir Putin’s atomic energy business inside the United States.” But that phrasing confuses the transactions involved. The bribery case involved the sale of commercial uranium sold by a Russian firm to US nuclear power plants. The Uranium One deal involved the purchase of US uranium deposits by another Russian firm. If Russia buying US uranium is bad for national security, might the United States buying Russian uranium then be good?

Was there anything new in the Hill article?

The Hill story does quote an attorney for a former FBI informant who claimed her client “witnessed numerous, detailed conversations in which Russian actors described their efforts to lobby, influence or ingratiate themselves with the Clintons in hopes of winning favorable uranium decisions from the Obama administration.” That claim gave GOP lawmakers an opening to press the Justice Department to lift a gag order restricting the informant from talking to them. In an indication of Republican interest in promoting the issue, Trump personally pressed subordinates to remove the gag order, CNN reported. The Justice Department, moving quickly, announced last Thursday that it had indeed lifted the order. Critics called Trump’s reported involvement inappropriate, a politically driven intervention in a criminal matter.

What is the real reason the story is back?

The story is back in the news now because Trump and his congressional allies want to distract from the real Russia scandal, critics say. Democratic lawmakers and staffers see the Uranium One fracas as the latest mini-tempest ginned up by the GOP in hopes of minimizing the focus on the spiraling scandal surrounding the Trump campaign’s interactions with Russia. “It’s a partisan effort aligned with what the White House has been urging, and Fox and Breitbart,” House Intelligence Committee ranking member Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) said last Wednesday on MSNBC.

What’s happening now on Capitol Hill?

Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and House Intelligence Committee chairman Devin Nunes (R-Calif.) both announced investigations of the Uranium One deal in the wake of the Hill article. Grassley had already sent letters requesting information from people involved in approving the deal; his focus on the matter has helped contribute to a breakdown in his committee’s once-bipartisan Russia investigation. Last week, Grassley went so far as to call for a special counsel to examine the matter. On Tuesday, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly seemed to echo that call.

Whoever in DOJ is capable w authority to appoint a special counsel shld do so to investigate Uranium One "whoever" means if u aren't recused

— ChuckGrassley (@ChuckGrassley) October 25, 2017

Both Grassley and Nunes in the past have eagerly used the ongoing congressional Russia investigations to target Democrats rather than Trump associates. “They’ve been throwing a lot against the wall and seeing what sticks,” said one senior Senate Democratic aide. “I think they are pretty happy with themselves and their ability to muddy the message.”