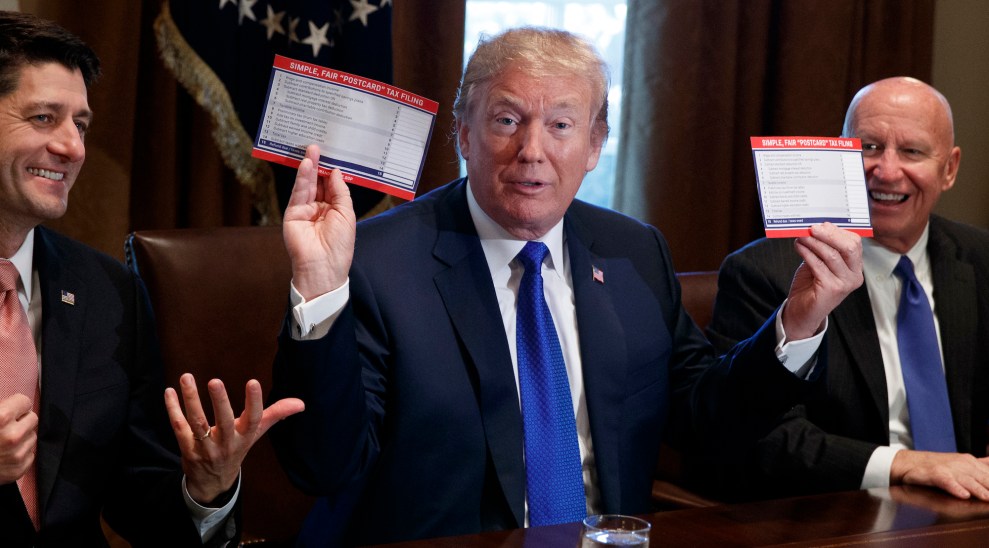

President Donald Trump holds Republicans' "postcard" tax form during a November meeting at the White House. Evan Vucci/AP

The initial analyses of House Republicans’ new tax cut bill are out, and they’re not looking good for the middle class. In the past few days, two think tanks, as well as Congress’ nonpartisan tax committee, have found that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would raise taxes on millions of Americans to help pay for corporate tax cuts that overwhelmingly benefit the wealthiest Americans. Even with 18 percent of households paying more to the government, the plan would still cost at least $1.5 trillion over 10 years.

A report released Sunday from the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) finds that about 45 percent of the Republicans’ tax cut would go to households making more than $500,000 per year—fewer than 1 percent of tax filers. Another report, released Monday by the the Institute on Taxation on Economic Policy (ITEP), a liberal think tank, also finds that nearly half the benefits would go to the top 1 percent.

The reports come as President Donald Trump sells his tax cut as a “big, beautiful Christmas present” to the American people. While it has been clear for months that the GOP’s proposal will disproportionately help the rich, the new estimates are the first to use the actual text of a Republican bill, rather than the general framework GOP leaders released in September. Tax experts now have enough detail to project that millions of families would end up paying more in taxes under the bill. On Sunday, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) maintained that everyone in the middle class will get a tax cut.

ITEP estimates that the top 1 percent of Americans would get a tax break of nearly $50,000 next year as a result of the legislation. By contrast, the group projects that the average middle-class taxpayer would get a $750 tax cut in 2018. That’s partly because a new $300-per-adult tax credit would still be in effect. After that proposed credit expires in 2023, the official estimate from Congress’ nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation predicts that the average household making between $20,000 and $40,000 per year would actually pay more taxes. (A preliminary estimate from the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center came to similar conclusions, but it was retracted Monday evening due to an error in its analysis of the bill’s child tax credit.)

The average middle-class family would still get a tax cut after the $300 credit expires, but not everyone in the middle class would benefit—despite top Republicans’ claims to the contrary. In fact, ITEP finds that about 1-in-5 middle-class households would pay more taxes in 2027 under the House bill. The GOP plan would also raise taxes on about one-third of well-off households that fall between the 80th and 95th income percentiles. The tax hikes are not evenly distributed across the country; they’re concentrated in areas with high state and local taxes, which are disproportionately affected by Republicans’ plan to gut deductions for state and local taxes. In Maryland, for instance, ITEP found that 62 percent of these well-off families who aren’t in the top 1 percent would pay more in taxes. At the same time, far wealthier Maryland families—those who do fall in the top 1 percent—will receive 93 percent of the benefits from the tax bill.

Republicans are likely to push back against these numbers, but to do so, they’d be admitting their bill relies on deceptive accounting. Under the budget resolution passed by the House and Senate, Republicans can add only $1.5 trillion in deficit spending over 10 years. But they’re in a bind over how to do that and still have room for their top policy priority: a permanent $100 billion per year corporate tax cut. To get around their self-imposed deficit limit, House Republicans are phasing out their new $300-per-adult tax credit after 5 years. Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Texas), the bill’s author, says the credit “will never go away” because Congress will renew it in five years—substantially increasing the cost of the tax cuts. The $300 credit is likely to be one of the most popular aspects of the plan, and the bill’s authors are counting on the fact that lawmakers will feel tremendous pressure to renew it when it expires. Critics of Brady’s accounting gimmick, such as the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, argue that a permanent $300 credit should be included in the bill’s cost if Republicans plan to keep it indefinitely.

David Kamin, a law professor at New York University who worked on tax policy in the Obama administration, writes that Americans shouldn’t be so sure Republicans will extend the credit. When it expires in 2023, Kamin projects that the budget deficit will be $1.2 trillion per year—up from about $700 billion today. With such a high deficit, Kamin says Republicans may balk at the prospect of taking on even more debt.

What’s easy to forget is that Republicans eventually hope to pay for the cuts by slashing funding for Medicare and Medicaid. On Sunday, House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) made that clear. “We’re just going to keep going at entitlement reform all the way down the road,” Ryan told Fox News’ Chris Wallace. Ryan said that will mean revisiting a 2017 House Budget proposal that would have decreased Medicare funding by almost $50 billion per year. Overall, Ryan’s budget would cut funding for programs that help working-class Americans by $2.9 trillion over the next decade.

Republicans such as Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin have tried to avoid talking about Ryan’s proposed entitlement cuts by saying the tax cut will pay for itself. Virtually no credible economists believe this. Even the Tax Foundation, Republicans’ favorite tax group, says the bill will cost almost $100 billion per year short after taking into account the growth Mnuchin is promising.

Update: A study released on Tuesday by the Joint Committee on Taxation finds that 25 percent of middle-class taxpayers would pay higher taxes in 2023, while 36 percent would receive more than $500 in tax cuts.

By 2027, 53 percent of all taxpayers would either be paying higher taxes or receiving less than $100 in tax cuts. Two-thirds of taxpayers making more than $1 million per year would get at least $500 in tax cuts—more than any other group.