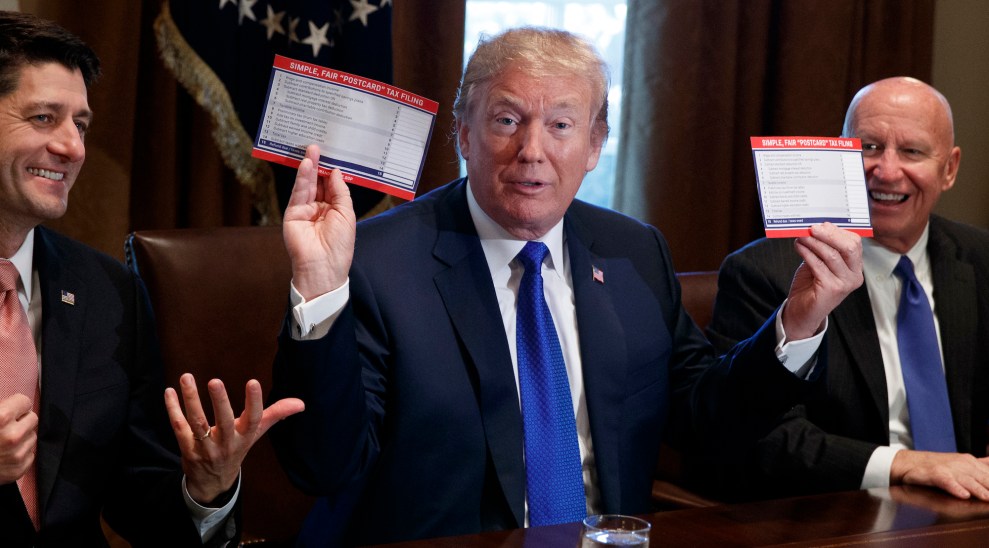

patrickheagney/Getty

On Thursday, Senate Republicans released a tax cut plan that closely tracks the business-friendly bill introduced last week in the House. But that bill has little chance of becoming law in its current form thanks to a Senate rule that requires 60 votes for legislation that adds to the deficit beyond 10 years.

In the past five days, three different studies have found that the House bill would provide nearly half of its benefits to the top 1 percent of Americans, while raising taxes on tens of millions of middle-class families. The Senate bill generally sticks to that approach.

Both the Senate and House bills, each named the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, would cut the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent, though the Senate bill would not make the switch until 2019. For individuals, the Senate bill would also create seven tax brackets ranging from 10 percent to 38.5 percent, compared to four brackets between 12 percent and 39.6 percent in the House.

Like the House bill, the Senate plan would lead to far more people taking the standard deduction, instead of itemizing their tax returns. But it gets there by a different route. Senate Republicans are keeping the current $1 million cap for deducting mortgage interest, while the House bill reduces it to $500,000. The Senate also broke with the House by keeping the deduction for medical expenses and student loan interest.

To offset the cost of keeping those deductions, Senate Republicans want to completely repeal the deduction for state and local taxes, instead of keeping it for up to $10,000 of property taxes. That is likely driven by political differences between the two chambers. In the House, Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) needs the votes of blue-state Republicans whose well-off constituents disproportionately use the state and local deduction. In the Senate, there are no Republicans representing the coastal states with higher taxes, such as California or Maryland, that benefit the most from the deduction. The Senate bill would also double the threshold for taxes on inheritances to $11 million per person, as opposed to eliminating it entirely as the House bill envisions. The Senate bill is still a major handout to the children of the rich since a more generous estate tax would only benefit about 1-in-500 of the richest Americans.

Despite those differences, both bills closely track the framework endorsed by President Donald Trump in September. That is likely to pose a procedural problem in the Senate. Both bodies have adopted budget resolutions that prevent them from adding more than $1.5 trillion of deficit-spending over the next 10 years. In the Senate, a parliamentary procedure known as the Byrd rule requires 60 votes for any legislation that adds to the deficit outside that 10-year budget window. If Republicans need 60 votes, the bill has virtually no chance of passing.

House Republicans are not even close to complying with the Byrd rule. On Monday, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton business school projected that their bill would add $2.6 trillion of deficit spending between 2028 and 2040. The Senate may not be in much better shape. Republican Senate staffers say they will need to change the bill to make it comply with the Byrd rule, the Wall Street Journal reports. That could require Republicans to make the corporate tax cuts temporary, which they’ve fought to avoid so far.

Corporations have appreciated that approach. On Wednesday, Trump’s economic council director Gary Cohn told CNBC’s John Harwood that, when it comes to Trump’s tax plan: “The most excited group out there are big CEOs.”