Reducing illegal immigration is one of President Donald Trump’s best known policy goals. But President Donald Trump has also insisted that curbing legal immigration must be a part of an immigration deal. Efforts to pass a bipartisan immigration bill have repeatedly stalled in Congress, with Trump rejecting any deals that do not address restrictions on legal immigration and provide funding for a border wall.

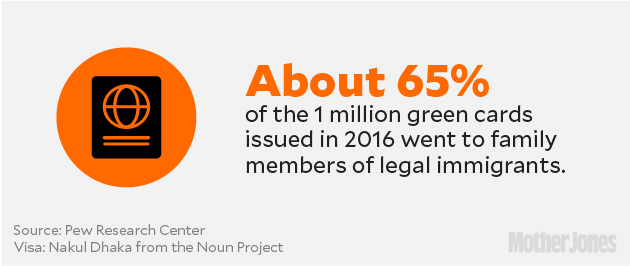

The White House’s immigration plan would put significant limits on legal family-based migration. Under the plan, legal immigrants could only sponsor their spouses and their minor children for legal permanent residency, the first step toward gaining citizenship. Citizens would no longer be able to sponsor their parents, grown children, or siblings for legal residency. Current green card holders would no longer be able to sponsor their adult children. The proposal draws heavily from the RAISE Act, legislation proposed last February by Republican senators Tom Cotton of Arkansas and David Perdue of Georgia. The changes would be applied “prospectively, not retroactively,” according to the White House, likely meaning that current applications would still be processed, but future applications would be blocked.

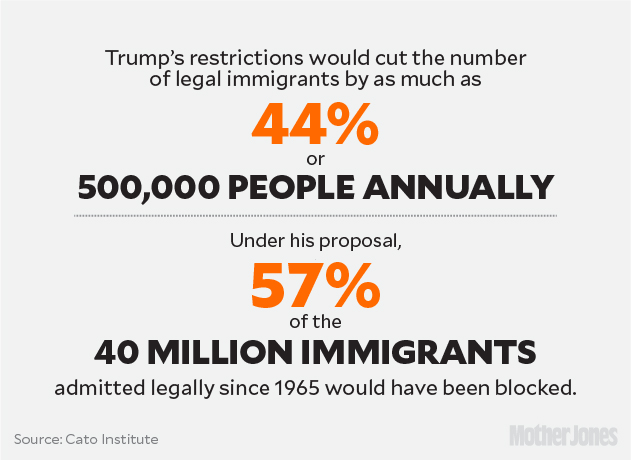

Trump’s proposal would be the largest policy cut to to legal immigration since the 1920s, and the largest immigration policy shift since 1965, according to the libertarian Cato Institute.

Anti-immigration activists have pushed for reducing family migration for years, often referring to the process as “chain migration.” Demographers first used the term in the ’60s to describe migration trends, but it has since become a politicized buzzword. The Trump administration has misleadingly characterized “chain migration” as a source of low-skilled immigrants who are admitted without limit or sufficient vetting.

“It conjures up this idea of a process that’s out of control, that draws people into the country without limitation,” says Julia Gelatt, an analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, a think tank in Washington, D.C. that studies immigration and refugee policies. Ignoring the term “family,” Gelatt notes, makes it easier to foster opposition to the policy. “It’s hard to argue against family reunification,” she says.

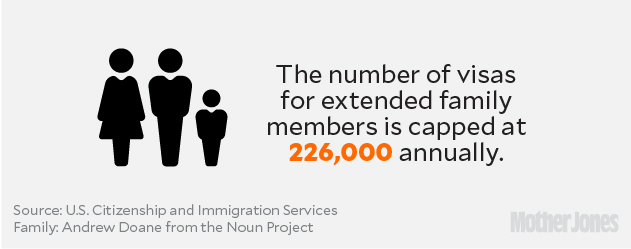

Family-based migration isn’t unlimited, and there are already a number of restrictions in place—including strict caps on the numbers of visas that can be issued in each country. As there are currently nearly 4 million people on the waiting list for visas, some family sponsorships can take up to 20 years, making it difficult to actually build a lengthy chain of relatives.

To apply for these visas, family members must to go through extensive background checks, medical screenings, and, in some cases, in-person interviews. Family-based migration has been a part of US immigration policy since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. It’s likely that First Lady Melania Trump’s parents, legal permanent residents who are in the process of obtaining citizenship, benefitted from the family sponsorship process, according to immigration lawyers interviewed by the Washington Post.

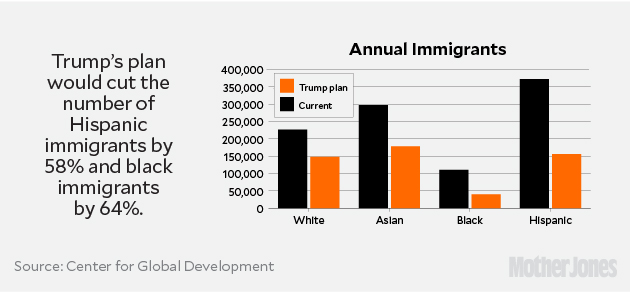

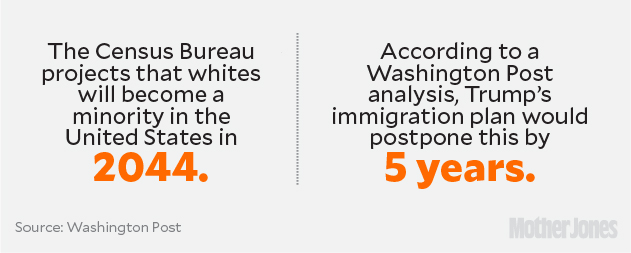

Trump’s immigration plan would also affect the demographics of immigrants coming into the country, according to analyses from the Center for Global Development, a think tank based in Washington, D.C., and the Washington Post.