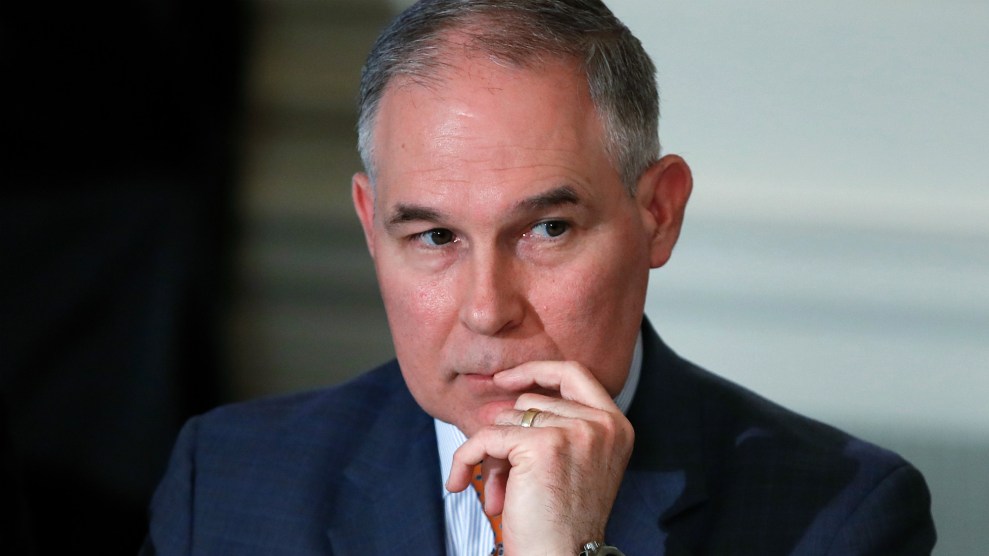

(AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Environmental Protection Agency administrator Scott Pruitt is under fire in Washington for his lavish travel expenses and for bunking in the townhouse of an energy lobbyist, but he also faces an ongoing controversy in Oklahoma connected to an allegedly corrupt buyout program to compensate residents of a catastrophically polluted mining town.

Tar Creek, in the northeastern corner of Oklahoma, once sat on one of the world’s largest deposits of lead-zinc, but the mining eventually petered out, leaving an environmental disaster in its wake. As old mine shafts collapsed, the land crumbled under residents’ homes. The town was declared a Superfund site in 1983, and the EPA embarked on cleanup effort that has cost more than $176 million. Meanwhile, a state program was launched with federal funding to purchase the homes of Tar Creek residents so they could relocate.

As Oklahoma’s attorney general, Pruitt investigated that program, which some residents contended doled out sweetheart deals to certain Tar Creek homeowners while offering a pittance to others. In 2014, he commissioned an audit that raised flags about the buyouts. Instead of prosecuting, Pruitt determined that the audit should be sealed from public scrutiny—a move the auditor himself described as “baffling.” The secrecy struck some Oklahomans as suspicious especially because Pruitt’s political ally, Sen. Jim Inhofe, helped to engineer the buyout program. Pruitt’s successor as Oklahoma’s attorney general, Mike Hunter, has maintained Pruitt’s position that the audit should not be released.

The Campaign for Accountability (CFA), a DC-based watchdog group, has been seeking the release of the audit. Last fall, it filed suit to force the state to release the report, litigation that is still pending. And on Thursday it filed suit against the EPA to find out whether Pruitt may have used his position with the agency to keep the audit—and any wrongdoing it may have uncovered—from seeing the light of day. The new suit contends that the agency has failed to respond to Freedom of Information Act requests for documents concerning whether Pruitt’s agency may have coordinated with Oklahoma officials to keep the audit under seal—and whether EPA officials may have leaked a 2013 report by the agency”s inspector general that downplayed allegations of wrongdoing in connection with the buyout program. In February, several news outlets obtained copies of the report.

Dan Stevens, executive director of CFA, says his group wants to know if Pruitt and his team have coordinated with Hunter back in Oklahoma, as well as whether EPA officials played any role in releasing the IG report.

“I don’t know for sure that it came from EPA—maybe someone out in Oklahoma had a copy of it lying around somewhere. But we definitely want to find out if Pruitt or his advisers released the IG report to the media,” Stevens says.

A spokeswoman for the EPA did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the lawsuit.