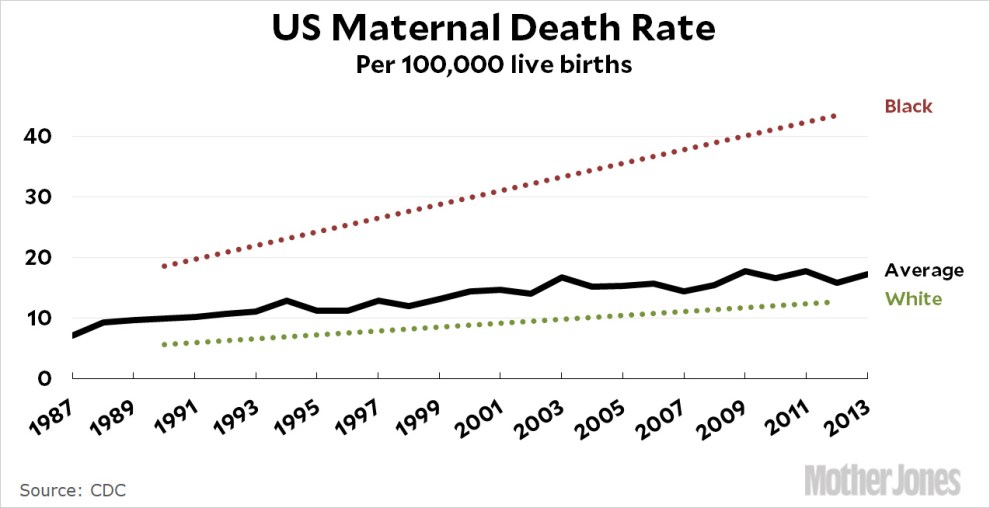

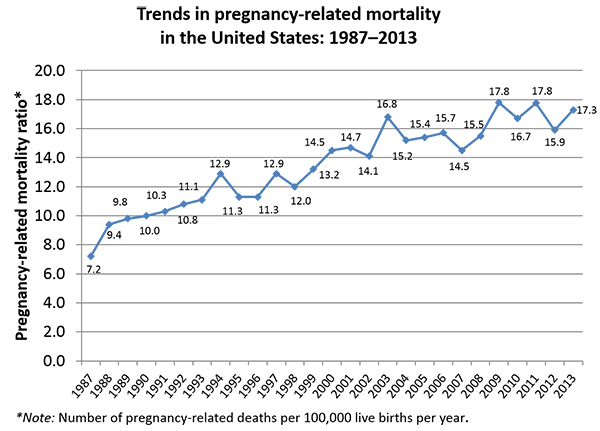

The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate of any developed nation. Every year, hundreds of American women still die in childbirth—and that number has increased over recent years.

Within these grim statistics, for certain groups, giving birth is especially dangerous: Black mothers die at three times the rate of their white counterparts.

So this week, women’s health advocates are meeting with lawmakers in Washington, DC, trying to persuade them to pass a suite of bills aimed at keeping mothers safe during labor, delivery, and the postpartum period. “Our aim is that in five years, this is going to change,” Ginger Breedlove, the founder of the maternal health nonprofit March for Moms, told Mother Jones.

The current round of federal legislation has two major goals: the first is to equip hospitals and state public health departments to better monitor mothers’ pregnancies, and the second is to bolster state and federal record keeping of maternal mortality rates.

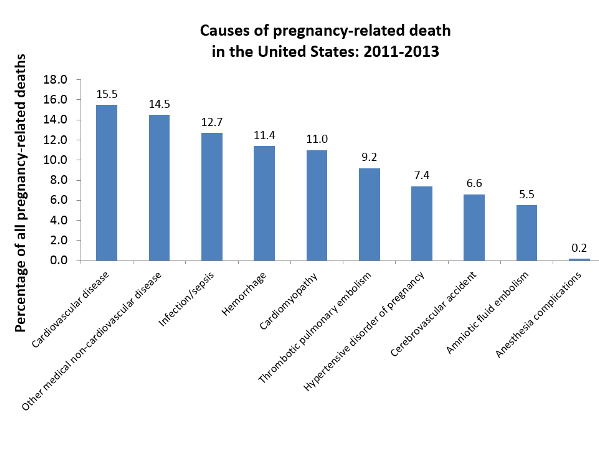

More than half of maternal deaths are considered preventable—and with adequate staffing, clinics could better identify women who have conditions that put them at risk for serious complications of childbirth. One of the bills would require the Health Resources and Services Administration to send maternity professionals—like obstetricians and midwives—to places where there’s a shortage, in order to provide better prenatal and labor and delivery care.

Two other bills would open up funds from the Health and Human Services Department for states to form or improve existing committees to record and analyze any deaths associated with childbirth and report them to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While 28 states currently have or are creating such committees, the processes by which they gather and report information has never been standardized. “There is no reason the United States should be the only industrialized country where maternal deaths are on the rise,“ said Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND), in a press conference last year when she introduced the legislation. “That’s unacceptable, and we need to get to the bottom of why that’s happening—and fast—and find solutions.”

The advocates hope that the bills, all three of which have bipartisan support, will be signed into law before Mother’s Day. “The health of a country comes from the health of its mothers and babies,” says Breedlove. “It’s devastating for those of us who are caregivers to think that these problems are being swept under the rug.”