Mother Jones illustration; Getty, Virginia Memory, New York Public Library

Jill Lepore has a problem with the way Americans talk about their history. “The United States is founded on a set of ideas,” the Harvard professor and New Yorker staff writer argues in her new book, These Truths. But “Americans have become so divided they no longer agree, if they ever did, about what those ideas are, or were.”

Over the last decade, the famously prolific Lepore has written book-length examinations of Wonder Woman, Greenwich Village gadfly Joe Gould, and the rise of the tea party, all while writing regularly about the nexus of history and politics for the New Yorker.

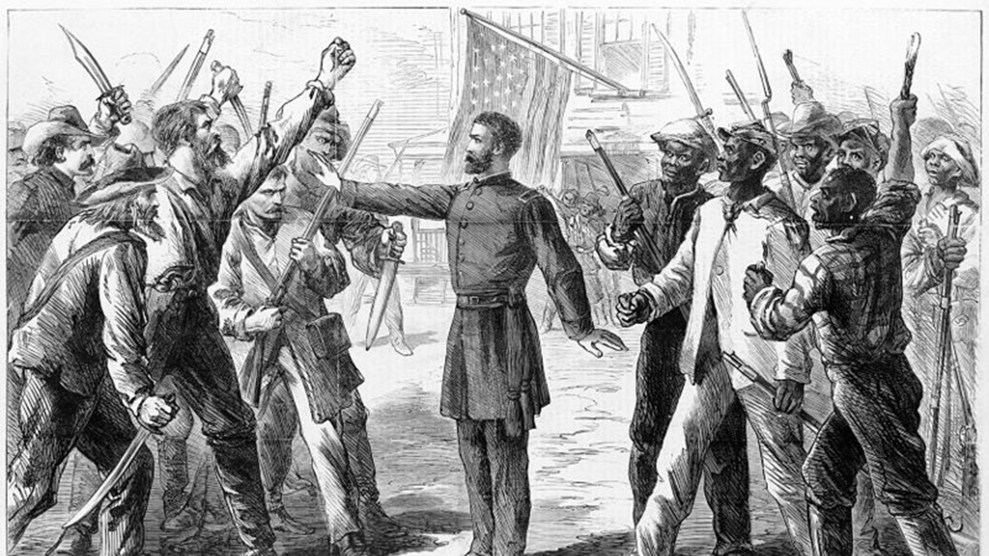

These Truths, out earlier this month, is an attempt to repackage American history into something resembling coherence. It is neither a Great Man history nor a full-on people’s history. We spend time with George Washington, but also his slave Harry. Ben Franklin is in here, but there’s even more about Jane, his sister who was the subject of yet another Lepore book. Lepore’s latest follows familiar contours, from Columbus to Trump, while hewing closely to some of her favorite themes: the evolution of the technology of communication, the lost-and-found nature of the historical record, and the endlessly shifting ways in which Americans have tried to make sense of a revolutionary system of government.

I reached out to Lepore to discuss the document hunt, Drunk History, and the less-than-glamorous personal lives of early Supreme Court justices.

Mother Jones: US history is not exactly untrampled ground. What did you think still needed to be said?

Jill Lepore: I was asked to write this book, but I agreed to do it in part because of the reporting I did on the tea party movement in 2009. I was teaching the American Revolution here at Harvard to undergraduates, and then in the evening I would ride my bike to Boston and go to a meeting of the tea party. The gap between the two versions of the American Revolution was remarkable and a bit troubling. I felt like that was the historical profession’s fault, honestly, for not doing enough to bring the rich scholarship of academic research to the wider public. It just seemed to be poisonous politically, that gap.

We live in a very polarized world, but the past seemed to be extremely polarized as well. So it seemed worthwhile to write an American history designed in some ways to address that gap.

MJ: You talk a lot in the book about the historical record—what survives and what doesn’t. Is there any missing source you wish you could get your hands on?

JL: There’s not a thing I write about where I don’t find something I was hoping to find or didn’t know existed that explained something in a new and fresh way. For me, that’s what gets me out of bed in the morning, those discoveries. I tend to write about stuff that puzzles me. And when something puzzles me, the last thing I’m interested in is my opinions about it. What I’m interested in is what the archive has to tell me about it. So that’s where I go looking.

There is actually a lot of archival stuff here I’ve found over the years that really means a lot to me. One story I tell in the 20th century chapters is about the birth of political consulting, which starts in 1932-33 in California with this company that has a wonderful name—Campaigns Inc.—run by a couple that later marries.

MJ: The Lie Factory!

JL: Yeah. The corporate records of Campaigns Inc. only enter the archives in maybe 2009. I was working on a story for the New Yorker and I just became obsessed with these people, because they invented the modern political campaign and left a very abundant paper trail explaining what they thought was important to do to win a political campaign. [Those records] filled in a lot of missing pieces for me in the giant jigsaw puzzle that is American political culture and how it is that politics became a business. It’s a real turning point. And it also explains how much political transformation, how much energy, is coming out of the state of California and out of political conflicts in California, and especially—by the time you get to the 1950s—how much of the modern conservative movement has to do with the politics of California.

MJ: You write about James Madison’s notes from the Constitutional Convention and the anticipation surrounding their release. Did people really think the publication of those journals would settle questions about the Constitution?

JL: I think people hoped they would find fodder for their political positions in Madison’s account of the Constitutional Convention. A lot of what I do in the book is try to explain what history is. What historical investigation, historical method, historical analysis consists of. What the historical record is and what it isn’t. What it tells us and what it doesn’t tell us. And so I linger for a long time at the outset over Columbus’ diary. What is that? Where is it? What does it mean? Should we believe anything that’s in it?

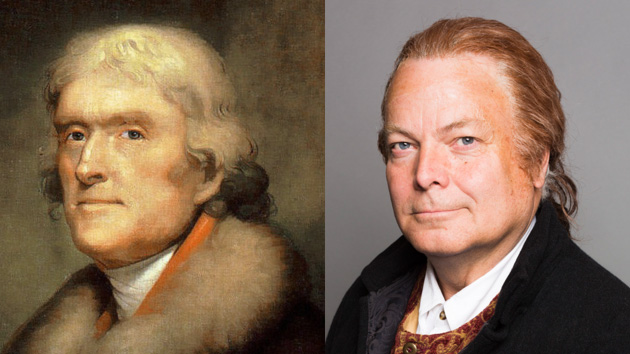

And I linger for a long time over the writing of the Constitution. It’s a sort of baffling document in many ways, especially for its first 50 years, because the delegates to the Constitutional Convention take a pledge to not reveal the contents of their deliberation for half a century, and Madison is the last one to die—and he also kept the best notes.

There’s a terrific book called Madison’s Hand about how he compulsively edited his notes year by year. He just couldn’t keep his mitts off them! He was the kind of writer that would want to be constantly revising, but also, the world was changing an awful lot and I think he maybe thought the historical record should be slightly different than it actually was. I’m not trying to nail James Madison, but it’s important to think about what that means and the power of actually being a witness to the writing of a whole frame of government—and then the power of keeping that secret for 50 years.

MJ: Did the 2016 election force you to change your mind about the more recent arcs in American history?

JL: When I’d begun writing, a big question for me was where to end. Historians, as a guild, don’t tend to like to write about the near present. I write a lot about the present—but we’re really told not to. There’s a beautiful book by John Gaddis called The Landscape of History. His lovely metaphor is that you need to be at the very top of a mountain, quite distant from the horizon, to get sufficient perspective on what’s going on.

But I was writing a slightly different book, and I felt I should take it up closer to the present. I will end on Inauguration Day 2009, the inauguration of Barack Obama—not for any partisan reason, but just as a great ending. It’s a kind of coming to terms with a long history of slavery and Jim Crow and the civil rights struggle.

And then Trump was elected, and I thought, “Oh, well, I can’t end with 2009.” It just seemed like a dereliction of duty. It was such an important election, a realigning and transformative moment in American political culture and in the larger history of the West. And that’s a different place to end. It’s like any narrative history; you have to have enough things seeded early on so the plant comes to bloom on Election Day.

It needed to be explained and also not over-explained. You don’t want the book to read as though the inevitable result of the march of American history is the election of Donald Trump.

MJ: Have you ever watched Drunk History?

JL: No.

MJ: Who or what have you read on American history recently that made you jealous—that was so good you wish you had done it?

JL: It’s a little bit like your question about Drunk History. This is my job. Like, if I was a NASCAR driver, I wouldn’t be spending my evenings test-driving cars and reading automotive magazines. I’d still be doing something else. There are a lot of historians whose work I love and admire, but when I’m doing my pleasure reading or my viral-watching or whatever the description of the Drunk History thing would be—

MJ: So do you try not to read US history in your off time?

JL: I read scholarship all the time. That’s what I do all day. I don’t know, do you read magazine journalism in your free time?

MJ: It’s usually a mix of some sort, yeah.

JL: I tend to read poetry and fiction. And I watch a lot of television.

MJ: Has the nostalgia for the founders always been as strong as it is these days? And has the divide between how people think about the founders ever been this strong?

JL: With the exception of the Hamilton musical, I don’t think it’s at some great peak right now. I think it was at a peak in the ‘90s, early 2000s. You don’t see a lot of either conservatives or liberals quoting 18th century thinkers. I can’t think of the most recent occasion of such a thing, whereas it was quite commonplace during the tea party moment. I mean, I guess there was that moment when Alex Jones told Donald Trump he was just like George Washington.

I was once at a dinner party in Canada—I don’t know why, it’s not like I’m a person who goes to dinner parties. One of the people there had been on a committee that drafted Canada’s current constitution, and he was a fantastic conversationalist. He thought it was very funny; it was sort of at the height of the originalist sensibility in popular culture, where intellectuals were trying to puzzle out like, what does originalism really mean?

He said, “There’s just no chance anybody in Canada would ever think, like, 200 years down the line, I was divinely inspired. It doesn’t matter how much time will pass.” He was besmirched because he was like any public figure of the early 21st century and just ineligible for canonization in a way the framers of the Constitution are immune to.

MJ: You mentioned Hamilton. Who else do you think is ripe for Broadway treatment?

JL: I didn’t think Hamilton was ripe for it.

MJ: [Laughs.]

JL: Like, people we would be better if we knew more about? That’s an endless list. People that would make good stories? That’s a different list. It seems to me worse than death to be the subject of a Broadway musical.

MJ: I think there are some people you hear their story and immediately think, “Oh, that’s a movie!” Lin-Manuel Miranda heard this story and thought he’s got to make a musical.

JL: You know the last song, where Hamilton’s widow talks about “Oh, how sad it is that history has forgotten Hamilton”? History never forgot Hamilton.

There’s a lot of new work going on. And new publications with the old work, including the memoirs of Pauli Murray, who’s really important. David Blight’s new biography of Frederick Douglass is coming out. There are tons of people I wish people knew more about.

MJ: You can only pack so much into 791 pages. What was the hardest thing to cut?

JL: Something I spent a lot of time on because it belonged and doesn’t happen to be naturally woven through most American history books is the history of technology and communication, the history of science. So there’s a lot in here on what the telegraph, the photograph, the radio, the early mainframe computer, personal computing did to American politics. I spent a lot of energy on the groundwork for an understanding of the intersection of technology and politics, so when we get to the near-present it doesn’t seem as though, suddenly, now technologies of communication affect political culture. That has been the case from the beginning—from the technology of speech, from the technology of writing.

MJ: I was especially interested to read about the early Supreme Court, which sounded like a really bad job. There was something about a justice trying to drown himself?

JL: It was a terrible job, partly because the Federalists so heavily undersold it. At the time of the ratification debates, there was a strong anti-Federalist sentiment that involved a particular critique of the powers accorded to the Supreme Court. There had been a long and hard-fought colonial opposition to the power the Crown had given justices in the colonies; they were appointed for life and too often had no legal training whatsoever. They just came in and issued these rulings and served “during the King’s pleasure”—a lovely term of art. So when the drafters of the Constitution come up with this new frame of government and have a fully equal third branch of government—this is a court that doesn’t exist under the Articles of Confederation. There is no federal judiciary before that. And then they serve for life.

So the wonderful, amazing (I actually adore Alexander Hamilton, nothing to do with the musical) Hamilton writes in Federalist No. 78, “Oh, but don’t worry, because the Supreme Court’s not gonna have any power; they’re the weakest branch—I mean, you really shouldn’t be worrying about the Supreme Court.” He talked it down so much that nobody really wants to belong to it.

People forget, but the Supreme Court was also a circuit court. You have to travel half the year and travel [then] was really hard—really, really hard. It takes a really long time to get anywhere. It’s physically quite uncomfortable. And then when you get there, you stay with like five other guys in a boarding house, all crammed into a bed together, and you’re far from your family.

So people just keep saying no when Washington asked them if they’ll serve on the Supreme Court. John Jay just quits and says, like, “My wife’s having a baby; I’m going home.” And when [Washington, DC] becomes the capital, the Supreme Court doesn’t have its own building; they meet in, like, somebody’s basement. It’s really not until John Marshall becomes Chief Justice that the court has considerably more dignity and decorum. They stop riding circuits. Marshall has everybody stay at the same boarding house in Washington.

MJ: Like a dorm?

JL: Yeah, like a hostel, so they can confer in some kind of secrecy. The court is the branch of government that changes the most. We tend to think of it as timeless because its current mystique is so powerful. The history of the Supreme Court is full of tragedy—but it’s also kind of hilarious.

MJ: It seemed like a point of emphasis that the court is not this static thing. John Roberts used the analogy that it was an umpire calling balls and strikes and that there’s a defined strike zone. Has that version of the Supreme Court ever really existed?

JL: It has existed as an aspiration. Aspiration is important and cynicism is for the dogs. There have been some incredible jurists who served on that bench with daunting distinction and integrity. And there have also been some incredibly low moments. It has always been a struggle for that court to have independence from the other branches and, late in the 19th century, to have independence from business interests. Whether it really has a coherent understanding of the law as a body is, I think, a question that has been continuous.

But I’m going to circle back to your earlier question: Why did I write the book, what was I trying to correct that has been left out? The book is not an indictment of other people’s accounts, but I do think we probably haven’t paid enough attention in our teaching of American history to basic manners of civics and the histories of democratic institutions. So everything we’ve seen as unprecedented and baffling or ruinous—there’s a weird shortsightedness of how we understand political institutions that can account for an inability to perceive their fragility and, paradoxically, can account for an artificial sense they’re much more fragile than they are.