Mother Jones illustration; Mbsydor/Wikimedia

In the first days of the #MeToo movement in October 2017, journalist Moira Donegan opened a Google spreadsheet, titled it “Shitty Media Men,” and shared it with female friends and colleagues, asking them to add the names rumored or alleged sexual abusers or harassers—and to keep it secret from men. By the time Donegan took it down 12 hours after sharing it, more than 70 men had been named, and copies were preserved elsewhere on the internet.

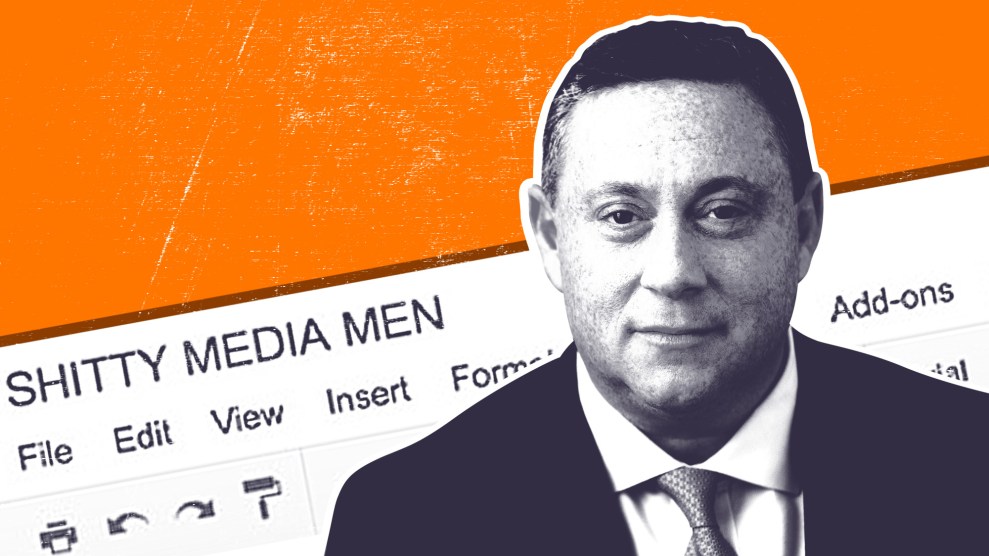

The list started such a firestorm of discussion about misogyny and sexual misconduct in the publishing world that Donegan was eventually compelled to publicly identify herself as its creator. And now one of the men named on the list, author Stephen Elliott, is suing Donegan and the list’s anonymous contributors for defamation and infliction of emotional distress.

According to Elliott’s complaint, filed Wednesday in a New York federal court, his inclusion on the document next to allegations of rape, harassment, and coercion (which he denies) contributed to low book sales and fewer business opportunities, loss of friends and social-media followers, and psychological suffering. His lawsuit accuses Donegan of maliciously publishing uncorroborated allegations against him because she hates men, and it cites statements she’s allegedly made on social media, like “the problem is men” and “I hate all men,” as evidence of her bad intentions. (For her part, Donegan has long maintained that the spreadsheet was an attempt to help women warn each other and protect themselves; as she wrote in January, “I only wanted to create a place for women to share their stories of harassment and assault without being needlessly discredited or judged.”)

Representing Elliott in his lawsuit is Andrew Miltenberg of Nesenoff & Miltenberg, a New York City lawyer who until several years ago had a modest reputation for business litigation, including defamation and First Amendment cases. But it’s Miltenberg’s more recent work that makes him a noteworthy choice: He’s spent the last five years making a name as one of the foremost defenders of male college students accused of sexual violence.

According to The Cut, in 2013, a former associate at Miltenberg’s firm brought him a new kind of client—a man who had been expelled from Vassar College for an alleged sexual assault—and an idea: Use Title IX, the federal law banning gender discrimination in education, to sue Vassar for discriminating against men accused of sexual violence. The Vassar case failed, but since then, Miltenberg has become the go-to lawyer for students facing allegations of sexual misconduct, representing them in code-of-conduct hearings that never make it to a real court, and filing lawsuits arguing that colleges are violating the due-process rights of the accused. As of late 2017, he’d been hired to represent about 150 students in college disciplinary hearings and lawsuits against nearly 50 schools, he told the New York Times. Business seems to be booming: Last year his firm opened an office in Boston dedicated to handling campus cases.

“This really can be looked at as it has nothing to do with men or women,” Miltenberg told Mother Jones in 2016. “The ramifications to an allegation of sexual assault or sexual misconduct are very severe…there have to be certain due processes in place in regard to why and how we hear these matters.”

Perhaps Miltenberg’s most famous client is Paul Nungesser, a former Columbia University student accused of sexual assault by Emma Sulkowicz, who became famous for protesting the school’s handling of her case by carrying around the mattress she claimed Nungesser assaulted her on. (Columbia’s investigation found Nungesser not responsible for sexual misconduct, and the university settled his lawsuit confidentially last year.) But the list of students Miltenberg has represented also includes a carefully selected plaintiff named Grant Neal, a former football player at Colorado State University-Pueblo, who was suspended for an encounter he claimed was consensual. (Neal and his university also settled last year, with neither admitting wrongdoing).

Neal’s case was Miltenberg’s first bid to broaden his litigation strategy and go after what many saw as the source of the problems with campus sexual assault proceedings: the landmark 2011 guidance issued by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, which laid out expectations for how federally funded schools should respond to reports of sexual violence. Campus sexual assault activists saw the guidance as the muscle survivors needed to get their schools to take their claims seriously and protect their right to an education without fear of violence. Yet in Neal’s case and in at least one other, Miltenberg asked federal judges to declare the Obama-era guidelines void, arguing that they were biased against men and had been improperly imposed on universities.

The lawsuits were part of a larger backlash—involving a loose coalition of law professors from schools like Harvard, organizations such as the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and fringe groups including SAVE: Stop Abusive and Violent Environments (which the Southern Poverty Law Center has identified as promoting misogyny)—against the increasing use of Title IX to protect student sexual assault victims. Last fall, these groups got their wish when Education Secretary Betsy DeVos rescinded the Obama administration’s Title IX guidance. (According to leaked draft regulations, DeVos is now planning to enact new rules that are much friendlier to accused students and put less pressure on universities to act when a student reports a sexual assault.) Federal courts have likewise handed several recent wins to accused students, including a September ruling in the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit that said universities must give accused perpetrators or their representatives a chance to directly cross-examine their alleged victims in campus hearings.

This successful effort to reverse the movement for campus survivors’ rights now seems like an omen for the broader #MeToo movement—especially after the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh despite multiple sexual assault allegations. (Kavanaugh’s supporters pleaded, Miltenberg-style, for “due process.”) But with his $1.5 million lawsuit, Elliott has gone a step further—claiming that allegations against him were not the fault of a survivor’s mixed-up memory, or of a misunderstanding, but of women like Donegan who, he claims, fabricate accusations out of hatred for men. The same idea animates the worst claims of the #HimToo backlash: that women, wanting to ruin men’s lives, will frequently lie about sexual assault, and that any man is vulnerable to a false allegation.

In college cases, Miltenberg found ways to turn these concerns about anti-male bias into powerful legal strategies. Perhaps it’s no surprise that he’s now levying the same arguments beyond campus boundaries.