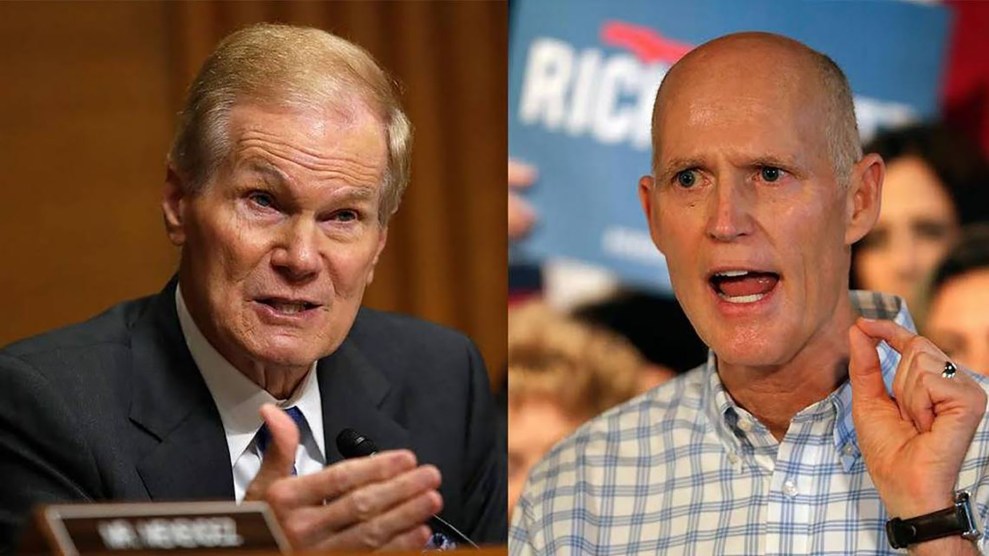

Democratic Sen. Bill Nelson and his Republican challenger, Florida Gov. Rick Scott. Miami Herald/TNS via ZUMA

The lawsuit phase of the Florida election recount has officially begun. While the national focus remains on the recount effort, particularly in Broward County, legal challenges from candidates and outside groups could alter the course of the race for US Senate, where .15 percent of the vote separates the candidates.

As was the case 18 years ago in the 2000 Florida recount, there remains a possibility that the election could be determined in court rather than at local election offices. Judges are reticent to insert themselves into the political process and pick winners, but the Senate race is close enough that a lawsuit to get thousands more ballots counted could change the outcome.

Gov. Rick Scott, the Republican candidate for Senate, currently leads incumbent Democrat Bill Nelson by 12,562 votes out of more than 8.2 million cast. In the governor’s race, also headed to a recount, Republican Ron DeSantis leads Democrat Andrew Gillum by 33,684 votes.

More than 50 lawsuits were filed in the month following the 2000 presidential election. In the week since the 2018 midterms, the number is likewise quickly multiplying. The Scott and Nelson campaigns, a Republican candidate for state agriculture commissioner, political parties, and outside groups have all filed lawsuits over elements of the election.

Nelson’s easiest route to victory is through the Broward County recount process, where his campaign has suggested there may be thousands of uncounted votes for Nelson that the tabulating machines are not picking up. A hand recount is likely to begin on Thursday in that race, and it could validate ballots that the machines excluded. But if the votes are not there, there are two lawsuits that could shift the election results in his favor. Since recounts very rarely change the outcome of elections, legal challenges—even longshot ones—could end up being Nelson’s last hope.

Listen to reporter Pema Levy report from outside the Broward County supervisor of elections’ office, as she awaits the results of Florida’s dramatic recount, on this week’s episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

Two days after the election, the Nelson campaign filed a lawsuit over Florida’s signature-match law, which requires local canvassing boards to evaluate the envelopes that contain vote-by-mail and provisional ballots and decide whether voters’ signatures match the ones on record with the elections office. This unscientific process results in thousands of discarded ballots every election cycle. Nelson’s case, filed in federal court in Tallahassee, seeks to require the Florida secretary of state to count these rejected vote-by-mail and provisional ballots, which disproportionately belong to Democratic-leaning populations, including young and African Americans voters.

It’s unclear how many votes Nelson might gain if he wins this case. The total number of absentee ballots rejected for signature issues is about 10,000. It’s likely that more than half were cast for Nelson, but that’s still not enough to erase his deficit. The number of provisional ballots rejected for signature problems is unknown.

Nelson also may have challenged the law too late. The judge could decide that the suit, filed after the election, can’t be used to change the process in this race. The signature-match issue may become part of the fight over the next election, rather than this one.

On Monday, the progressive nonprofit VoteVets, the Democratic National Committee, and the Senate Democrats’ campaign arm filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking to force the state to accept mail-in-ballots that arrived after the deadline. In many states, absentee ballots simply have to be postmarked by a certain date, but under Florida law, election officials can only count ballots that are received by 7 p.m. on election night, or 10 days later for oversees voters. The lawsuit argues that it is unconstitutional to disenfranchise voters through uncontrollable factors like delayed mail delivery.

“A Floridian who is in Paris, France, gets to have their ballot postmarked the day before the election, and if that ballot is received up to 10 days after the election, that ballot counts,” election attorney Marc Elias, who is representing the groups filing the suit, said on a Monday conference call with reporters. (Elias is also representing the Nelson campaign in its legal challenges.) But “if they live in Miami-Dade and they cast their ballot on the same day and it doesn’t get there till the day after the election, it doesn’t count. This doesn’t make any sense.”

Like the other lawsuit, this one could suffer from being brought after the election rather than before. But there’s a chance the case could resonate with the federal judge on the case, Mark Walker. On the eve of the 2016 election, Walker ruled on a case with clear parallels. At the time, Florida law gave voters who failed to sign their absentee ballot envelopes a chance to fix the issue but did not offer a remedy to voters whose signatures were found not to match. Walker ruled it unconstitutional to treat these two groups differently. “It is illogical, irrational, and patently bizarre for the state of Florida to withhold the opportunity to cure from mismatched-signature voters while providing that same opportunity to no-signature voters,” Walker wrote at the time.

Other lawsuits have been more administrative and symbolic. Days after the election, Scott’s campaign sued the Broward County elections supervisor, Brenda Snipes, for failing to comply with open records requests in a timely fashion. It also sued the supervisor of elections in Palm Beach County, Susan Bucher, for mishandling the processing of absentee ballots. Judges issued orders favorable to Scott in both cases, but neither was expected to alter the vote count.

Scott’s campaign filed new complaints against both counties on Sunday, asking the courts to seize ballots and election equipment to prevent fraud. But on Monday, a judge in Broward County rejected Scott’s request, finding that the campaign had produced no concrete evidence of a security risk. The Scott campaign’s complaints appeared aimed in part at shaping the public narrative that there is fraud in these two Democratic counties, a claim Scott himself has made in seeking to wrap up the counting process and declare victory.

Hours after Monday’s hearing, two watchdog groups filed a lawsuit against Scott to force him to recuse himself, as governor, from all involvement in the election. Their case alleges that Scott has demonstrated bias that makes his continued role in the election—including his official role in certifying the results—unconstitutional.

Scott has shown a willingness to use the governorship to influence the outcome of the race, the suit alleges. Last Thursday, as his lead narrowed as more votes were counted, Scott held a campaign news conference on the porch of the governor’s mansion and accused the Broward and Palm Beach county supervisors of “rampant fraud.” That location is generally reserved for state business, not campaign speeches. In the same speech, Scott asked the Florida Department of Law Enforcement to investigate fraud in the counting effort, which Democrats viewed as an abuse of his power as governor. (The head of the department responded that there was no evidence of fraud to investigate.) The event blurred the lines between Scott the candidate making campaign allegations and Scott the governor, who oversees Florida’s law enforcement and election officials.

The lawsuit cites this press conference, as well as Scott’s unsubstantiated talk of voter fraud, as evidence that he “has demonstrated actual bias in the conduct of his office with respect to the administration of the state’s 2018 elections.” The suit is unlikely to sway the outcome of the election, but a forced recusal would send the message that Scott has crossed a line in his dual role as candidate and governor. “Using his governor’s authority, he has tried to literally send in the police,” Elias said. “I think that it ought to cause the people of Florida to be concerned that the governor is not thinking clearly in executing his authority as governor.”

The Florida recount debacle in 2000 spurred election reform in Florida and around the country. Though lawsuits over this recount may fail to change the outcome of the race, they have already brought attention to numerous problems with election administration, inefficiency, laws that disenfranchise voters, and the conflict of interest that comes when the people on the ballot are also in charge of the election.