Alabama state senator Trip Pittman had always sort of questioned whether nursery schools were worth the investment. Pittman, a conservative Republican, figured the kinds of things you’re supposed to learn before kindergarten—washing your hands, tying your shoes, minding your manners—might best be taught by parents and grandparents at home. Conservatives often argue that kids who attend preschool fare no better than those who don’t. So in 2013, when a proposal came before the Legislature to expand a state preschool program for four-year-olds, Pittman was on the fence.

The folks from the Alabama School Readiness Alliance, a group backing the proposal, were persistent, though. They were sure they could win the senator over if only he would come see the program in action, and so one day he did. Pittman visited a preschool in Prichard, a small, long-struggling city near Mobile, and came away captivated. “I watched the interaction between the teachers and the students,” he recalls. “It seemed remarkable, the fact that you could assimilate children into a classroom environment—raising their hands, going down the hall, being inquisitive. It was really impressive the way the teachers interacted with kids.” The team also showed him data on outcomes for children living in poverty: Sixth-grade preschool alums scored about 9 percent higher on state tests than those who hadn’t attended, and third-grade alums scored 13 percent higher than their peers. “The results I saw,” Pittman says, “were dramatic.”

By many measures, the people of Alabama aren’t doing well. It’s one of the poorest and sickest states in the nation, with high rates of hunger, obesity, heart disease, and deaths from cancer. Test scores are much lower than the national average. In 2017, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a child advocacy group, ranked the state’s educational system 42nd in the nation. But its preschools have been an oasis on that dismal landscape. In 2013, just 7 percent of Alabama four-year-olds participated in the program, which is open to all. By 2017, almost one-quarter did, and Alabama was one of only three states to meet all 10 of the nationally recognized benchmarks for preschool quality, outperforming even states like Massachusetts that are known for great public education.

In the six years that Alabama has collected data on the program, its graduates have consistently outperformed their fellow students. “People look at Alabama and they don’t think of it as No. 1 in anything,” says Allison Muhlendorf, who heads the School Readiness Alliance. “But we’re very proud to be No. 1 in pre-K quality.”

This success has implications well beyond Alabama’s borders. It is the first real test, in the reddest of red states, of the notion that investing in early education can improve not only children’s outcomes, but entire economies. For years, many Republicans have argued that any preschool gains fade by the third grade—and they have used this claim to try to dismantle public preschool programs. In 2014, Rep. Paul Ryan famously charged that Head Start, the federal program that provides free preschool to poor families, was “failing to prepare children for school.” Alabama’s results fly in the face of such arguments. And its program never would have been possible without the support of a committed group of businesspeople and lawmakers—many of them as conservative as they come.

During the first few years of life, the human brain grows with incredible speed, from about a quarter of the size of an adult’s at birth to 90 percent by age six. Some regions undergo particularly dramatic changes—namely the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for complex reasoning, decision making, and navigation of social relationships, says Laurel Gabard-Durnam, a postdoctoral fellow who studies brain development at Boston Children’s Hospital. “What looks like casual play is actually this incredibly complicated set of cognitive processes that all work together to improve the way that you think and regulate yourself.”

Teacher Elise Parker with preschool students at Pintlala Elementary School

William Widmer

It would thus stand to reason that preschool would have a profound impact on how children learn. But over the last decade, some widely publicized research suggested the opposite. For a 2015 paper, researchers at Vanderbilt University followed about 1,100 Tennessee children from pre-K through third grade. By the end of kindergarten, they observed, the benefits of preschool seemed to wear off. And then, shockingly, the preschool grads actually began to fare worse than their peers. The study created a stir, and Gov. Bill Haslam said he would reevaluate preschool funding.

But lost in the shuffle was the fact that Tennessee’s program had issues. Its preschools were overenrolled and underfunded, with no system in place to make sure classrooms followed the guidelines. The study acknowledged as much, noting, “The idea that pre-k can be scaled up quickly, cheaply, and without professional support or vision is certainly bound to be incorrect.”

Abundant research, on the other hand, shows that high-quality preschools—with small class sizes, low student-teacher ratios, and robust teacher pay, training, and oversight—can have dramatic and lifelong benefits. Consider the Perry Preschool study, which in 1962 began tracking 123 African American three-year-olds from low-income families in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Throughout their lives, the 58 children randomly assigned to a top-notch preschool program have outperformed the kids who didn’t attend. At age five, more than two-thirds of the preschoolers scored 90 or better on an IQ test, compared with 28 percent of the non-preschoolers. Three-quarters of the preschoolers graduated from high school, versus 60 percent of the others. At 27, more than a quarter owned homes, compared with just 5 percent of the non-preschoolers. And by 40, nearly half of the non-preschool group had been arrested at some point for violent crimes, while less than one-third of the preschool group had.

A more recent study, from 2016, tracked 1,700 children, some of whom attended Head Start in Tulsa, Oklahoma. In middle school, the attendees had higher math scores and lower truancy than students who didn’t attend. That same year, James Heckman, a Nobel Prize recipient in economics, analyzed preschool data from North Carolina and concluded that states that invest in quality early childhood education stimulate their economies with higher-achieving workers and spend less money than they would have on remedial education, health, and criminal justice. Overall, he calculated, states could see annual returns of up to 13 percent. “Early education is one of the best investments we can make,” President Barack Obama noted in a 2014 speech. “Not just in a child’s future, but in our country.”

Such thinking is catching on. According to the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at Rutgers University, 16 states now serve more than one-third of their four-year-olds, up from just three states plus DC in 2002, and state preschool expenditures have more than doubled to $7.6 billion. But spending per child (a data point that correlates closely with program quality) has declined. And preschool budgets vary dramatically from place to place: In 2017, Washington, DC, invested nearly $17,000 per child. Nebraska spent less than $2,000. Seven states spent nothing at all.

The federal government plays an important role in all of this—it funds Head Start, for one. But in a recent op-ed, NIEER founder Steven Barnett noted that Head Start’s 2018 budget was so small that it had to delay plans to expand beyond an average of three and a half hours per day of instruction. (The Trump administration has proposed further cuts.) The White House also administers the Preschool Development Grants Program, which contributed more than $230 million to state preschools during the 2016-17 school year, according to NIEER. The Trump administration has targeted this program for elimination.

How did Alabama, of all places, end up with some of the nation’s most effective preschools? It wasn’t by accident. Much of the credit goes to the program’s key architect, a quiet powerhouse named Jeana Ross.

As a young teacher in a poor, rural part of the state during the 1970s, Ross noticed that her students learned better through play and experiences than from a teacher droning on. When she realized most of them had never been to a beach, she thought, “Well, I can’t bring them to the beach, but I can give them a sense of the beach by bringing in sand and letting them taste salt water.”

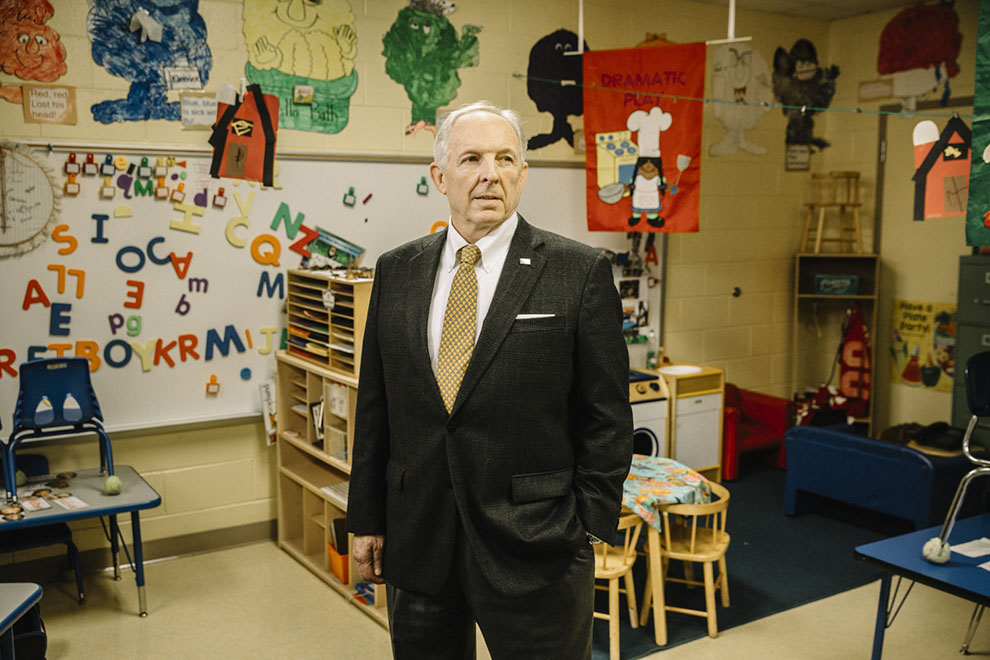

Jeana Ross, Alabama’s secretary of childhood education, in a preschool classroom at Pintlala Elementary

William Widmer

She eventually quit teaching to raise her own children. After they were grown, in the late 1990s, some friends persuaded her to join them in starting a rural preschool. Ross was put in charge of curriculum, “so I looked at the kindergarten standards and asked myself, ‘What do they need to know?’” Impressed, her supervisor asked her to develop a preschool curriculum for the entire county. Over the next 15 years, she worked in school systems across the state, leaving behind “a sprinkling” of preschool programs that helped spawn what Alabama calls its First Class Pre-K program.

Ross, now the state’s secretary of early childhood education, always knew preschool was powerful. Kindergarten teachers loved it, because preschool grads arrived ready to learn. But to expand the state program, Ross and others would have to convince lawmakers it made fiscal sense. For that, they would need the help of Alabama’s most powerful influencers: its businesspeople.

Bob Powers runs a successful insurance and real estate agency in Eufaula, in the southeastern part of the state. He also co-chairs an education committee for the Business Council of Alabama and is a board president of the School Readiness Alliance Task Force, a coalition of activists, businesses, and educators behind the preschool push.

A dozen years ago, Powers told me, businesses were “clamoring for better workers.” They wanted to see high school graduates with better training and more technical competence. Then, in 2007, he attended a presentation in Colorado that changed the way he viewed the problem. The presenter talked about the work of Heckman, the Nobel laureate. If businesses really wanted better workers, Heckman’s research suggested, their best bet was to get involved before kindergarten. Fascinated, Powers shared the findings with the business council.

Backed by a $100,000 grant from the Pew Charitable Trusts, the council spread the gospel to fellow businesspeople. Among them was Michael Luce, a Republican donor, vice chair of a Birmingham-based investment firm, and an early member of the School Readiness Alliance Task Force. “When I read the statistics about the return on investment when you put kids in really good pre-K, I couldn’t believe it!” he told me.

Alabama businessman Bob Powers at the Early Education Center in Eufaula

William Widmer

Luce and other leaders decided to pony up cash for a comprehensive evaluation of the preschool program—he footed half the bill himself, and the Birmingham Business Alliance kicked in the rest. The alliance then teamed up with Ross to promote an ambitious legislative proposal that read like a business plan. It proved convincing. In 2012, the Alabama Legislature voted to boost preschool spending by about $9 million, a 47 percent bump. During the 2016-17 school year, the state spent almost $100 million on the program.

It seems to be paying off. By third grade, a 2016 analysis showed, preschool participants scored significantly higher than non-preschoolers on state math and reading tests. Low-income kids showed double-digit improvements, and black kids saw the biggest gains of all: up 16 percent in math and 20 percent in reading compared with black children who didn’t attend. “We hoped that quality preschool would benefit the most at-risk students,” Muhlendorf told me. “It’s surpassed our expectations.”

One Tuesday morning last fall, I visited a preschool in the rural community of Pintlala, outside Montgomery. Roughly half the students were black, and half were white. At least 40 percent of them came from low-income families.

If you don’t know what to look for, preschool classrooms can all seem pretty similar. I saw many of the same trappings in Pintlala that I noticed in my two-year-old’s day care center: art supplies, blocks, a play kitchen. But as I toured the space with Muhlendorf and a team from the state’s early childhood department, I began to see how much thought had been put into every space. The goal was to tempt kids into initiating lessons themselves rather than passively absorbing information from a teacher.

I also noticed thoughtful displays and activities designed to help kids develop social skills and emotional awareness. A banner with movable Velcro-backed photos laid out the day’s schedule, imparting a sense of structure and routine. A poster showed children’s chores for the week. One job was “helper,” and the dress-up corner included costumes for “community helpers”: firefighters, police officers, doctors. The playacting can spark conversations about how different jobs contribute to a community. There was also a quiet corner where kids could catch a break if they felt overwhelmed or upset, a strategy meant to head off discipline problems before they arise. Research shows that kids who attend preschools that focus on social and emotional growth—things like learning to manage strong emotions and be sensitive to others—have higher achievement and fewer behavior problems down the road. “Anyone can learn their ABCs and 123s in any sham of a pre-K program,” Muhlendorf told me. “It’s the soft skills that lead to the better outcomes. We had to have outcomes if it was going to fly in Alabama.”

While a traditional pre-K might use worksheets to teach numbers and letters, the Pintlala classroom offered paper and crayons, dry-erase boards, chalkboards, and Magna Doodles to entice kids to form letters. Play areas had writing materials, too, so teachers could use fun activities to spark impromptu word lessons. The math corner was full of neat things to count: colorful toy bears, plastic geometric shapes, interlocking blocks. In the nature and science corner, the team pointed out a box full of objects of different textures collected from the outdoors—pinecones, shells, branches.

Before a free-play session, the two teachers herded the class into a circle and asked each child to make a plan: Did she want to play with blocks? Feed a doll? Do an art project? After play began, the teachers walked around and asked each one about his or her activities. When the circle reconvened, the kids took turns talking about their choices. Did they stick to their plan or try something else? These planning and reviewing steps are meant to help children hone their language abilities and set the stage for time management skills they will need later on.

Such rich interactions only happen when the teachers are excellent. Alabama encourages this in several ways: It has at least one teacher for every 10 kids. And while many states don’t require preschool teachers to have a degree and don’t pay them as much as elementary school teachers get, Alabama hires only credentialed preschool teachers and gives them elementary school salaries. What’s more, the teachers, who reflect the ethnic diversity of their students, meet regularly with trained coaches and spend at least 20 hours each year on professional development.

During one such workshop at the state’s early childhood education headquarters in Montgomery, I watched as a group of teachers learned to use everyday conversations as an opportunity for language development. If a child said she had eaten spaghetti for dinner, for instance, one natural response might be to talk about that day’s lunch menu—a conversation stopper, the instructor warned. Instead, she said, teachers should probe deeper: Did you help Dad make dinner? What were the ingredients? It sounds like you used a colander. That’s the thing you use to drain the hot water from the noodles. Can you find me a colander in the play kitchen?

Skills aside, such workshops show teachers the state considers their work important. Pintlala teacher Christi Self confesses that when her principal moved her from first grade to pre-K, “I was upset because I was thinking that this was just a babysitting job, and I have two degrees.” But “I quickly learned that this is not a babysitting job,” she adds. “This is where the natural learning process begins.”

Teacher Christi Self supervises Pintlala preschool students at outdoor playtime.

William Widmer

Should any lawmakers grouse about the expense, Luce is prepared to remind them that not paying for preschool will cost a lot more. “We’re not just trying to get kids to go to pre-K,” he says. “We’re positioning them to graduate from high school and beyond.” NIEER’s Barnett hopes more states will catch on—but good luck with that if President Donald Trump keeps targeting preschool funding. “A really good program requires a robust budget to get off the ground,” Barnett says.

Alabama has that. When Gov. Kay Ivey learned of the program’s recent successes, she put out a press release: “Now we must work to take the methods of instruction in Pre-K and implement them into kindergarten, first, second and third grade classrooms.” That could be doable, Muhlendorf says: “The coaches and the regional staff that support the teachers in the classroom—I think that’s something that could be replicated in K-12.”

Back in Pintlala, I watched as Self visited each area of her classroom, asking questions and encouraging the children as they played. In the writing area, one little boy had his head down on a desk. An early childhood staffer there for my visit scooped the boy into her lap. “Are you tired?” she asked. “Do you need some quiet time?” Children notice when you recognize how they’re feeling, Self told me. After relaxing for a few minutes, the boy made his way back to the writing table. Self joined him and they picked up where they’d left off. “I can see you’re ready to learn,” she said.