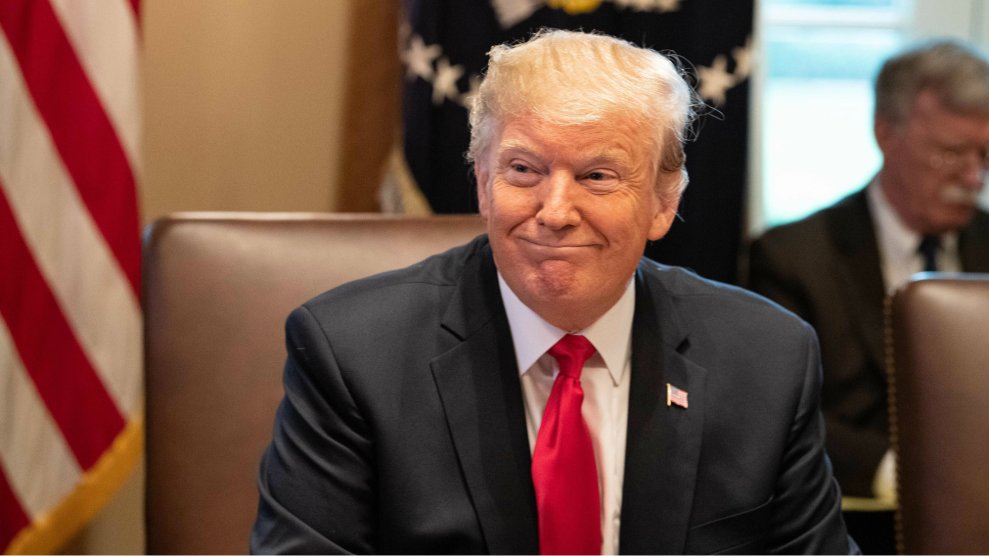

Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images

President Donald Trump’s tenuous relationship with the military he commands took another awkward turn last week when he ordered the Pentagon to block the publication of independent reports that have been harshly critical of reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan.

“What kind of stuff is this?” he asked during a televised meeting with his Cabinet, suggesting that information released by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) could be a security risk. “The enemy reads those reports; they study every line of it…. I don’t want it to happen anymore, Mr. Secretary. You understand that.”

Over the past 11 years, SIGAR has probed the management of the more than $130 billion spent in Afghanistan, holding the United States and its Afghan partners accountable for embezzlement and waste in what has became the most expensive reconstruction effort in American history. By its own estimation, the office has recovered more than $951 million from fines and settlements. Its most recent report, released in October, contained the startling conclusion that Afghan government forces now control the least amount of territory of any point in the past three years.

While nearly every federal agency has an inspector general, an auditor who investigates claims of misconduct and, on occasion, refers matters to the Justice Department for prosecution, Congress set up SIGAR to be more independent. Even though many of its staffers are drawn from the Department of Defense, it is run separately from the Pentagon. However, acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan has the legal ability to order its reports classified, according to Mandy Smithberger of the Project on Government Oversight. The organization sent a letter to Shanahan last week urging him to reject Trump’s order, warning of an “an unprecedented and dangerous attempt to silence these important watchdogs.”

The president’s demand at the Cabinet meeting that future investigations “should be private reports and be locked up” is consistent with other steps his administration has taken to limit government transparency and accountability, from cracking down on leakers to withholding information on the number of American troops in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

“Those reports do have intelligence value,” says Andrew Bacevich, a military historian at Boston University who has been critical of US actions in Afghanistan and Iraq, though not the sort of sensitive information the president suggested he was concerned about: “Cumulatively, they emphasize—it’s really irrefutable—we don’t know how to rebuild this country.”

Trump’s comments came during a week in which several top Pentagon officials departed and Shanahan, a historically inexperienced acting secretary, took over. Defense officials did not rush to provide a public reaction, and the Pentagon did not respond to a request for comment. SIGAR spokeswoman Lauren Mick told Mother Jones that the office “has not released a statement and has no comment.”

Since taking charge of SIGAR in 2012, Special Inspector General John Sopko has generated waves of publicity for a series of reports lambasting Pentagon officials for inefficiently managing resources in Afghanistan. Attention-grabbing details from the reports—$6.1 million to import nine Italian goats, $43 million to build a single gas station—have featured in news stories, but drawn questions for lacking broader context. For example, the $43 million figure was later challenged by a senior DOD official, who said the entire project only cost $5.1 million. And those goats created “hundreds” of jobs, according to a Politico story on Sopko’s record, which quoted a detractor deriding him as “the Donald Trump of inspectors general.”

While Shanahan’s predecessor, retired general James Mattis, rarely contradicted his commander in chief publicly, he demonstrated a willingness to bury undesirable White House proposals in red tape. While Trump has so far praised Shanahan—and even indicated that he might leave him running the Pentagon indefinitely—his willingness to comply with the president’s request represents an early, and fast-approaching, test of their relationship: SIGAR’s next quarterly report is set to be released on January 31.