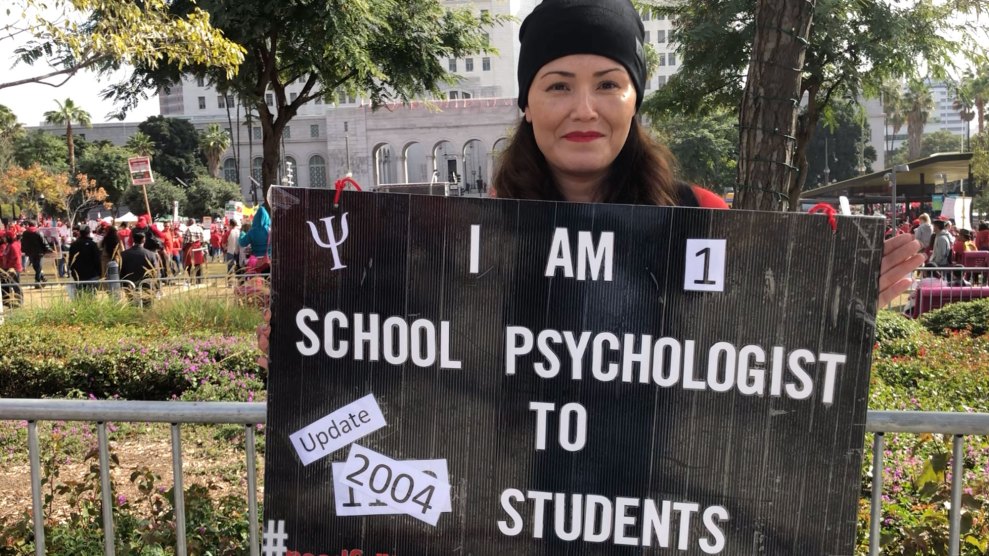

Alejandra Gurrola travels between three elementary schools in Los Angeles to work with students. Edwin Rios/Mother Jones

At a rally Friday afternoon outside Los Angeles City Hall, Alejandra Gurrola stared out at a sea of teachers and supporters clad in red. She used to be one of them. Now, she had a related but different concern, as spelled out on the sign she held: “I am 1 school psychologist to 2004 students.”

Gurrola started working in Los Angeles schools in 1995 as a teacher’s assistant. She later became a teacher at a middle school in Boyle Heights for seven years. During that time, she noticed that funding cuts had slashed programs like art courses and electives. “A lot of things that back then we took for granted have now been cut,” Gurrola says.

She became a school psychologist and now jumps between three different K-5 elementary schools 25 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles. “I saw the need in our students, so I looked at what else I can do besides being the caring teacher,” Gurrola says.

What about when you have a school psychologist at a school? How about three? Here’s Alejandra Gurrola, who moves betweeen three elementary schools in San Fernando Valley and works with 2000+ students. pic.twitter.com/ZXpMcSwqfd

— Edwin Rios (@Edwin_D_Rios) January 18, 2019

The weeklong teachers’ strike—which appears set to soon come to an end after the district and union announced a deal Tuesday—concerned many objections from teachers, ranging from too low of pay to high class sizes. But one of the most frequent concerns I heard at Friday’s rally and talking to teachers along picket lines was that the school district had not devoted enough money to hiring support staffers like counselors, nurses, and school psychologists.

Gurrola hoped that the district and teachers could agree on a “fair contract” and called for more funding to address the need. She hoped the district could eventually hire enough staffers for schools to reduce her caseload to 750 students for every school psychologist. For her, that would mean concentrating on students at one school. “We are spread among multiple schools. That’s unacceptable,” Gurrola says. “It interferes with our quality of work because we don’t have enough time to serve as many students as we could.”

The deal announced Tuesday addresses some of those issues. According to the union’s summary of the tentative deal, the district would retroactively increase teacher salaries by 6 percent and eliminate a provision that gave the district more authority to raise class sizes under certain circumstances. Under the deal, the district would also hire at least 17 counselors by October 2019, keeping a counselor to student ratio of 500:1, and hire at least 300 nurses, enough to have a full-time nurse stationed at each school for a week in the next two school years. The district would also hire at least 80 librarians.

In the nation’s second-largest school district, where nearly three-quarters of students are Latino, Gurrola noted that beyond cramped classrooms and academic demands, one of the biggest stressors among the students she works with has been the uncertainty of life under President Donald Trump’s strict immigration policies, particularly for undocumented families. “We have had a lot of students just stressed out about it. They come to school and they’re crying or they’re just constantly worried. Their anxiety levels are so high, and it’s all because that’s what they’re thinking about,” Gurrola says. “How could they concentrate on their studies if they are thinking about mom and dad?”

“What if a student is having an emotional crisis on a Tuesday and I’m not there because I’m assigned to another school?” she asks. “Then the resource for that student is not there for that day.”