Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call

The field of Democratic candidates running for president in 2020 is still taking shape, but so far the contenders have agreed on one policy: Cash from corporate political action committees (PACs) is bad. That’s not an entirely new idea—in 2008 and 2012 Barack Obama rejected donations from corporate PACs, though Hillary Clinton didn’t repeat that pledge in 2016—but it’s quickly becoming an early litmus test for presidential contenders when it comes to campaign finance.

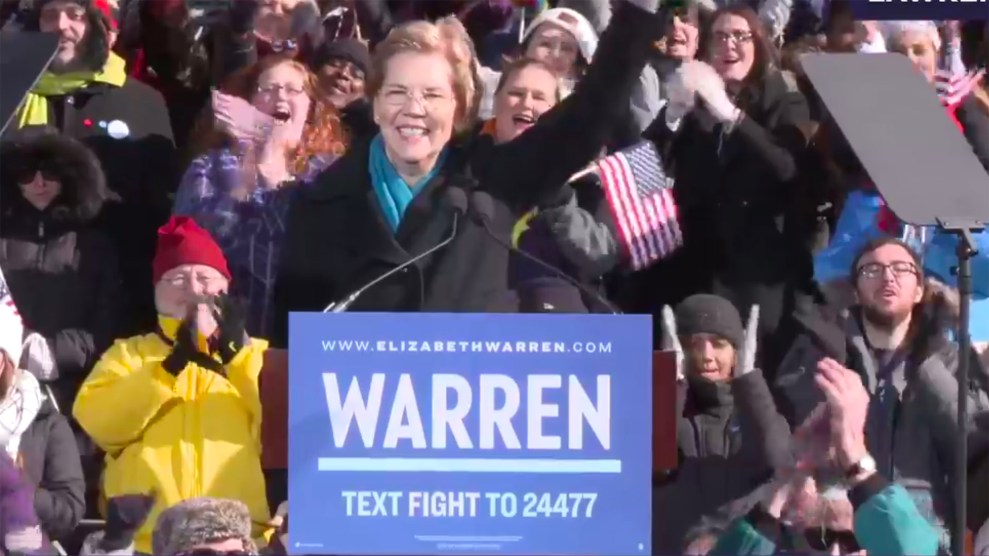

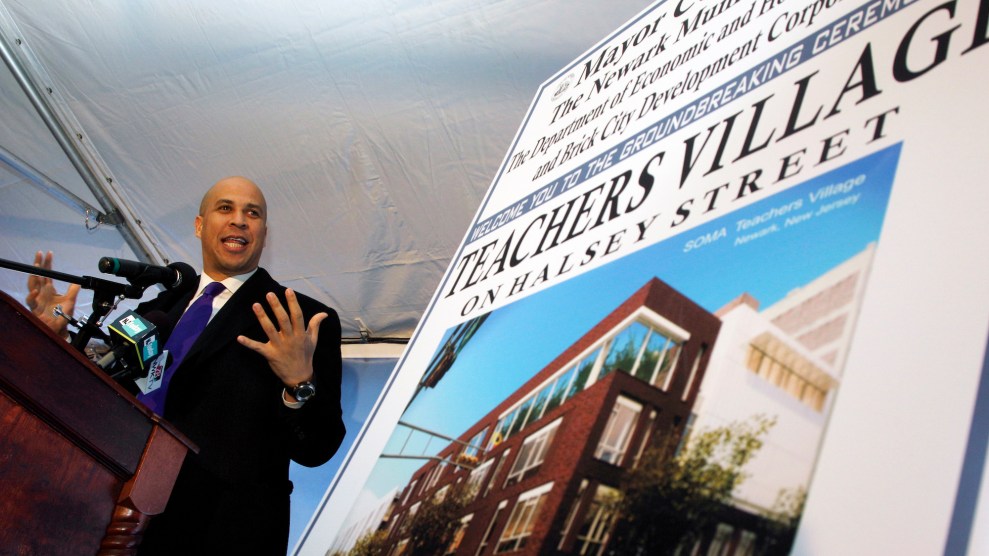

To date, Sens. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), and Kirstin Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), as well as Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii) and former San Antonio Mayor Julian Castro, have all vowed not to take corporate PAC dollars for their 2020 campaigns, attempting to portray their independence from corporate influence. “I don’t believe democracy should be for sale to billionaires and giant corporations,” Warren said during a campaign event last month.

There’s no legal definition for what exactly is and is not a corporate PAC, though it’s generally considered to be any donation directly to a candidate—or to the politician’s leadership PAC, a separate fund that can be used to redistribute money to other candidates—that comes from a political action committee that is directly connected to a for-profit business.

Corporate PACs aren’t big players in the campaign finance world for presidential elections, so most candidates aren’t really giving up that much money. “I think the corporate PAC pledge is basically a signifier for how a candidate approaches the broader issue of money in politics,” says Daniel Weiner, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. “In that regard, it is not without value, but the practical significance of refusing these particular donations is not that great.”

The PACs are capped at donating a maximum of $10,000 to each candidate for the 2020 election, a comparatively small sum in the age of super-PACs that can spend unlimited amounts on messaging and advertisements. And corporate PACs tend to not be especially ideological, mainly supporting incumbents from both parties or donating to both candidates in the same races to benefit themselves regardless of who wins. PAC money in general from corporations or other groups has played a very small role in recent presidential campaigns, with less than 1 percent of all contributions for any major party nominee coming from PACs in the last four presidential elections, according to data from the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

“The amount of money that candidates are leaving behind isn’t huge,” says Michael Beckel, head of research and policy at Issue One, a nonprofit advocacy group that wants to reduce the influence of big money in politics. “But it’s a step that shows voters they want to be serious about campaign finance reform and making Washington work for the people, not special interests. It’s a small step, but a symbolic one that could resonate with voters.”

It has become increasingly common to run without the help of corporate PAC funds. In the House, 50 Democrats and two Republicans have said they won’t accept corporate donations, with individual small-dollar donors propelling most of the challengers in the 2018 midterms.

That’s carried over to Democrats who want to be on the top of the ticket in 2020. Gillibrand, for example, announced last February that she would no longer accept corporate PAC money while she was running for reelection in 2018. “I believe the flood of special interest and secret money into campaigns is corrosive and leading to corruption both hard and soft in Congress,” Gillibrand said at the time.

Prior to the past year, though, many of the 2020 candidates didn’t shy away from corporate dollars. Corporate PACs donated more than $506,000 to Gillibrand between 2013 and 2018, according to an analysis by MapLight, a nonprofit that tracks money in politics. In the past six years, Gillibrand received thousands of dollars in corporate PAC donations from Wall Street (Citigroup, New York Life Insurance, UBS) and the tech sector (Facebook, Google, Sony), among others. “Senator Gillibrand will not accept federal lobbyist or corporate PAC money in her run for president in 2020, and she does not think candidates should have individual Super PACs,” Meredith Kelly, Gillibrand’s communication director, told Mother Jones in an email.

Harris announced last year that she would no longer take corporate PAC money. Between 2013 and 2018, Harris received $203,532 from corporate PACs, with thousands of dollars in part from her home state’s tech sector (Cisco, Google, Sony). Booker also fell in line by vowing not to take donations from corporate PACs early last year. However, he has taken over $1.3 million from corporate PACs in the past six years, including during his 2014 Senate campaign. Booker received thousands of dollars from Wall Street (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase & Co.), the tech sector (Amazon, Facebook, Google), telecommunications (AT&T, Comcast, Verizon), and the pharmaceutical industry (Pfizer, Merck).

Warren has been one of the most vocal candidates against corporate PAC money, particularly in the past few weeks since she announced her presidential campaign. “I don’t take corporate PAC money. Shoot, I don’t take PAC money of any kind,” she said at a campaign stop in Iowa. She has also called all Democratic candidates in the 2020 primary to disavow super-PACs and not self-fund (which mostly pertains to billionaire candidates). Warren pledged to reject all PAC money of any kind in an anti-corruption speech in August and said she would stop taking corporate PAC money in the first half of last year, which had never been a big part of her fundraising strategy. She received a little over $22,000 from corporate PACs between 2013 and 2018.

While corporate PACs may have never been the biggest source of outside money, outside groups that push campaign finance reform say that these pledges could affect their approach to 2020. “At minimum, the corporate PAC pledge will be a major factor in our decision-making process on who to support in the 2020 election,” says Adam Bozzi, communications director of End Citizens United, a group that supports the overhaul of campaign finance laws. “We think it’s good policy, the right thing to do, and that candidates should use it as a baseline for how to fundraise for their campaigns.”