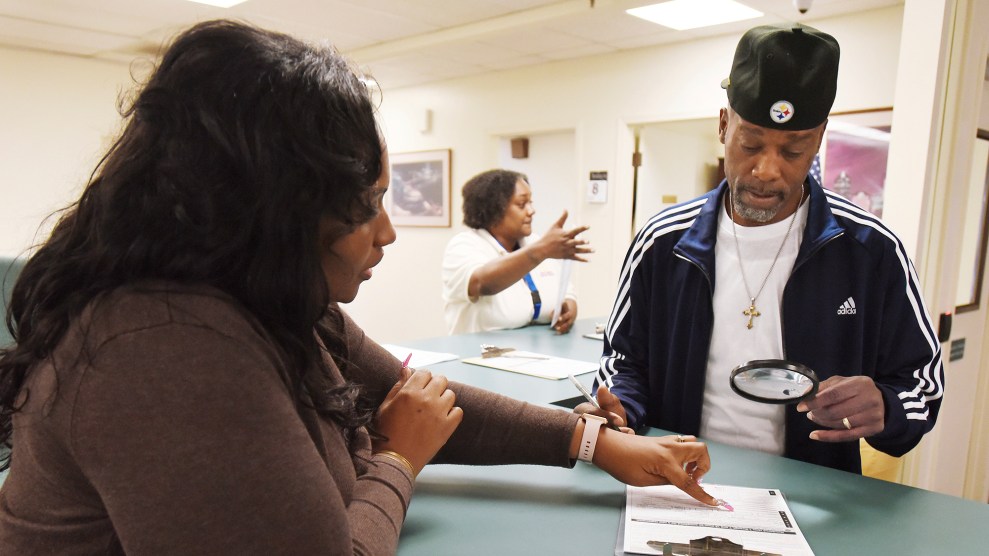

An elections office clerk helps Anthony Biggins fill out his voter registration paperwork for the first time in his life in Jacksonville on January 8 Bob Self/The Florida Times-Union via AP

Last week, Republican lawmakers in Florida advanced a House bill that would require people with felony records to pay off all court fines and fees before registering to vote, a proposal that critics likened to a poll tax. And they’re not done trying to restrict voting rights: They also want to exclude people from the rolls by redefining what it means to commit certain crimes.

Amendment 4, a ballot measure that passed last November, changed the state constitution to restore voting rights to up to 1.4 million people who finished serving their sentences for most felonies. Previously, Florida was one of only four states that permanently blocked people with felony records from the polls, a policy that traced back to the Jim Crow era and prevented 10 percent of Floridians—including about 1 in 5 African Americans in the state—from participating in elections. The ballot measure, which went into effect in January, was the country’s biggest expansion of voting rights in decades.

The ballot measure restored the right to vote to former felons except those who were “convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense.” Now Republican lawmakers argue that the language of the bill wasn’t clear enough; they’re attempting to create definitions of “murder” and “felony sexual offense” that go beyond what the drafters of Amendment 4 intended.

On Monday, Republicans in a state Senate committee advanced a bill that says “murder” includes a host of crimes, including first-degree and second-degree murder, but also attempted murder, the unintended killing of someone during the course of committing another felony, and the “unlawful killing of an unborn child, by any injury to the mother.” (An earlier version of Senate Bill 7086 also included manslaughter on the list of murder crimes, but that offense was removed in an amendment approved on Monday.) Sen. Jeff Brandes, a Republican who helped draft the legislation, said it made sense to add “attempted murder” to the definition of murder, even if nobody had died. “Obviously murder—first degree, second degree—to me, that means attempted murder, because there’s intent,” he told the Tampa Bay Times.

Backers of Amendment 4 disagree, saying they did not mean to exclude so many people from voting with their ballot measure. “I don’t think ‘attempted murder’ is written anywhere within our [ballot measure’s] constitutional language,” Desmond Meade, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Council, which worked to get Amendment 4 on the ballot, told the newspaper.

Kirk Bailey, political director of the ACLU of Florida, which also helped push for Amendment 4, adds that under Florida law, injuring a mother in a way that terminates her pregnancy is considered a form of homicide but not murder. “Our position is murder means murder—it means first- or second-degree murder as defined in Florida statute,” he says.

Florida Republicans are also trying to broaden the definition of “felony sexual crimes.” In the bill moving through the state House, they define this to include even offenses like the placement of an adult entertainment store within 2,500 feet of a school. “That’s not what ‘felony sexual offense’ means,” says Bailey, adding that Florida statutes clearly delineate which crimes can land a person on the sex offender registry, and that these are the exceptions intended by Amendment 4. The House bill passed out of one committee last week and must go through two more committees, he says.

Rep. James Grant, chairman of Florida’s House criminal justice subcommittee, suggests the definition should go beyond crimes linked with the sex offender registry. “When the [ballot measure] says ‘felony sex offenses’ and that means nothing legally, the best I can do is propose a list of felonies that are sexual,” he told the Orlando Sentinel. “The reality is I’m going to do my best effort to maintain what I believe the rule of law now requires in a super-ambiguous constitutional amendment.”

If enacted, the ACLU estimates, the expanded definitions of murder and sexual offenses could prevent thousands of Floridians from registering to vote. Even more people—tens of thousands —would likely be barred from the rolls if required to pay back all the court fines and fees laid out in the two bills.

“What Florida voters intended is already clear,” Bailey said in a statement as the Senate bill advanced Monday. “We urge lawmakers to uphold the will of Florida voters, stand for second chances, and withdraw this restrictive bill.”