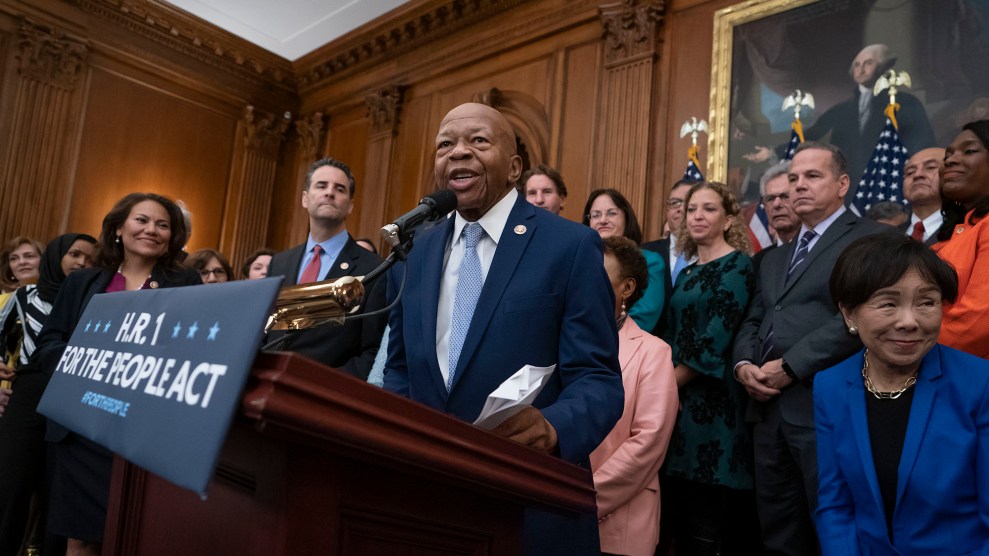

Rep. Elijah Cummings, chair of the House oversight committee, joins House Democrats to introduce HR 1 on January 4.J. Scott Applewhite/AP

The House of Representatives on Friday passed the most significant democracy reform bill introduced in Congress since the Watergate era by a vote of 234 to 193. The sweeping bill, known as HR 1: the For the People Act, would massively expand voting rights, crack down on gerrymandering, reduce the influence of big money in politics, and require sitting presidents and presidential candidates to release 10 years of tax returns.

“It’s one of the most comprehensive packages of democracy reform we’ve seen in a generation,” Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.), the chief sponsor of the bill, told Mother Jones.

Every House Democrat present voted for the bill and every House Republican voted no. It passed a day after the 54th anniversary of the Bloody Sunday march in Selma, Alabama, which helped spur passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But its prospects are far dimmer in the Republican-controlled Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has declared his opposition to the bill, calling it “the Democrat Politician Protection Act.” The Trump administration has also stated its opposition.

The 622-page bill, the first introduced by House Democrats in early January, would establish nationwide automatic voter registration, Election Day registration, and two weeks of early voting in every state. It would curb gerrymandering by requiring independent commissions, instead of partisan state legislatures, to draw congressional maps. To reduce the influence of megadonors on elections, it would create a small-donor matching system to publicly finance congressional campaigns and require dark-money groups to disclose their donors. Finally, it would enact new ethics reforms, among them requiring the president and vice president, along with future candidates for those offices, to release 10 years of personal and business tax returns.

While these ideas have been introduced in different pieces of legislation, HR 1 is the first bill to combine a broad array of reforms aimed at expanding access to—and fairness in—elections. “The public wants to see reform in all of these areas,” says Sarbanes. “It’s not enough if you enhance their opportunities at the ballot box, but they feel like the people they elect get to Washington and don’t behave or get captured by big money. And it’s not enough to fix the influence that money has if it’s still too hard to vote.”

McConnell has expressed his fervent opposition to even relatively uncontroversial sections of the bill, such as making Election Day a federal holiday in order to give people more time to vote. McConnell called this a “power grab” for Democrats, a striking admission that Republicans do better when fewer people vote.

Even though the bill will not pass the Senate anytime soon, Sarbanes thinks Democratic support for it will only increase if McConnell becomes the face of opposition to it. He said House Democrats will now “take HR 1 on tour,” using it to build public support for a democratic reform agenda and lay the groundwork for its passage when there’s a Senate and president more amenable to it, possibly after 2020.

For now, it’s telling that House Democrats made HR 1 the first bill they introduced and one of the first they passed. It shows how once-marginalized “good government” issues have become a top priority for Democrats.