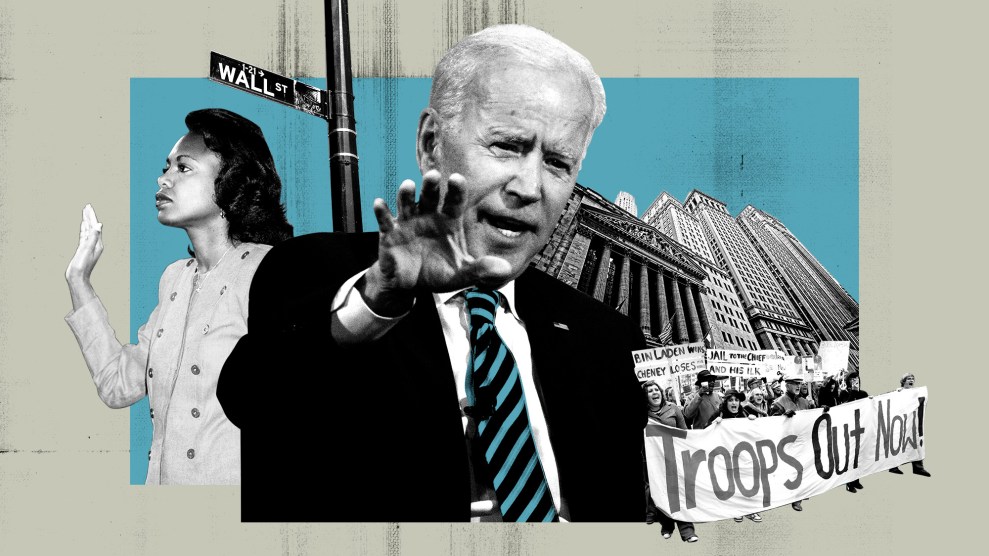

Mother Jones illustration

Yet again, Joe Biden is running for president.

Biden, the six-term senator from Delaware and Barack Obama’s vice president, unsuccessfully sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988 and 2008 and considered running again in 2016. But following his son Beau’s death from brain cancer in May 2015, he decided against it. He formally announced his latest presidential run in a video on Thursday morning. Then he is scheduled to hit a union hall in Pittsburgh on Monday before a tour of four early voting states.

In the lead-up to his entry into the race, Biden’s schedule was packed with events that seem aimed at demonstrating he has modernized his brand on issues of race, gender, and other matters: participating in a Memphis, Tennessee, civil rights event, and delivering a Columbia Law School talk about the legacy of the Violence Against Women Act, which he authored. Much of this seems designed to address what many progressives see as Biden’s liability: His decades-long record of public service has been punctuated by his ties to the banking industry, his treatment of Anita Hill, his civil rights–era opposition to busing, and other actions out of sync with today’s Democratic Party. Biden offers his political foes a handful of easy targets, as he joins a crowded, mostly progressive Democratic field where candidates are vying for the support of a more left-leaning Democratic electorate.

Here is some of the baggage from his 45 years in politics and government that may weigh him down in the 2020 contest:

Big Banks and Bankruptcy Reform

Biden’s close ties with the banking industry—an important economic force in his home state of Delaware and a major donor to his Senate campaigns—has long been a sore point for his progressive critics. For instance, Delaware financial services company MBNA, now a Bank of America subsidiary, was for decades Biden’s top campaign contributor and also hired his son Hunter out of law school.

In the late 1990s, the financial industry mounted a lobbying campaign to get legislation passed that would make it harder for average families to file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy—the kind that allows consumers to wipe their slates clean of most debts. The legislation made its way to Congress in 2000, and Biden, one of three Democratic senators on the Senate committee working on the bill, voiced his support for it in a floor speech after President Bill Clinton threatened to veto the measure—reportedly at Hillary Clinton’s urging. In 2001, following the election of President George W. Bush, Biden co-sponsored similar legislation that passed the Senate but died in the House. The measure resurfaced four years later and with Biden’s support made it through the Senate to Bush’s desk for his signature.

Biden’s championing of this bill has resurfaced every time he has sought higher office—especially given Democrats’ growing distaste for Wall Street after the 2008 financial crisis. As he faces off against 2020 candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, who have both called for tougher banking oversight, Biden’s friendliness with banks will likely prove politically problematic, especially as dozens of new Democratic lawmakers and other presidential hopefuls have openly rejected corporate PAC money and influence.

Anita Hill and the Clarence Thomas Confirmation Hearings

In 1991, Biden, as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, presided over the confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas to become Supreme Court justice. After University of Oklahoma law professor Anita Hill alleged that Thomas sexually harassed her when she was an employee, her charges became a central focus of those hearings. Biden was widely criticized for his treatment of Hill during the sessions, especially his decision to allow aggressive questioning of Hill by a panel exclusively comprising white men—while he prevented three women from testifying about other instances of alleged inappropriate behavior by Thomas. In recent years, Biden has publicly apologized more than once, as he did at a New York event last month when he said, “To this day, I regret I couldn’t come up with a way to get her the kind of hearing she deserved, given the courage she showed by reaching out to us.” Hill’s defenders read these statements as weak attempts that obscure the power he had at the time to control the hearing.

Plagiarism Problems

During the 1988 Democratic presidential primary, Biden admitted to lifting five pages of a law review article without attribution for a law school paper. At the time, Biden said it was not “malevolent” and he had just misunderstood the citation standards. During the same campaign, Biden also faced accusations of plagiarizing portions of his stump speeches from Robert Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey, and British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock. Biden called the claims “much ado about nothing” and said his failure to attribute properly was inadvertent. Still, within weeks of the accusations, Biden left the presidential race. As Biden has sought higher office in recent years, pundits and critics have revisited this story, often in the context of plagiarism allegations against other political actors—for instance, when Melania Trump was accused of plagiarizing her Republican National Convention speech from Michelle Obama.

Record on Race

Biden has built a reputation as a warrior for the civil rights of women and the LGBTQ community. He famously helped push Barack Obama to embrace marriage equality when the first-term president was still “evolving” on the issue. But during his first several decades as a lawmaker, Biden made several moves that cut against the drive for racial equality. He opposed busing aimed at integrating school districts, eulogized a segregationist, and advanced tough-on-crime policies that have disproportionately incarcerated black Americans.

In his 1972 Senate campaign, Biden supported integrating schools and using busing to do so. Once elected, however, he voted for anti-busing Senate bills, claiming he still favored school integration but now opposed this approach as a way to do it. During one debate on the Senate floor, Biden said, “I have become convinced that busing is a bankrupt concept,” as he backed an anti-busing measure sponsored by avowed segregationist Sen. Jesse Helms. When a federally mandated integration program was set to begin in Biden’s home state in the late 1970s, the Delaware senator co-sponsored an amendment, tacked on to an education appropriations bill, which would have limited courts’ ability to order busing and imposed a halt on all pending busing orders around the country. The Washington Post at the time called it “the most far-reaching antibusing measure to receive serious consideration in the Senate.” (It failed by a slim margin.)

In 2003, Biden traveled to South Carolina to give a eulogy for South Carolina Republican Sen. Strom Thurmond. A longtime segregationist, Thurmond was known for his ardent 1960s opposition to legislation aimed at expanding the rights of black Americans. In his eulogy, Biden noted that Thurmond was a product of his time and background and highlighted his apparent change on issues of race as he grew older, citing Thurmond’s support for the Voting Rights Act. Many see this speech as evidence of Biden’s ability to build connection and civility with his political opponents. But with racial inequality at the forefront of many voter’s minds—and with a Democratic primary field unprecedented in diversity of gender and race—Biden’s Thurmond tribute could become a political liability.

Tough on Crime

After taking the helm of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the late 1980s, Biden championed legislation that overhauled the American criminal justice system—first the 1988 Anti-Drug Abuse Act and later the 1994 crime bill. Taken together, these bills—which increased sentences for offenses involving drugs most prominent in low-income and nonwhite communities—funded new prisons and enacted a provision requiring mandatory life sentences for certain offenders. Advocates have criticized these measures for leading to a dramatic expansion in mass incarceration, disproportionately hurting black communities.

Support for the Iraq War

In the 2020 field, Biden is one of two Democratic candidates who participated in the Iraq war debate in Congress after 9/11. (Sen. Bernie Sanders is the other.) When President George W. Bush first called on Congress to pass a measure that would grant him the authority to launch the war, Biden crafted an alternative resolution to slow down Bush’s rush to war. The measure gained bipartisan support but ultimately failed. During the October 2002 floor fight on the issue, Biden said he did not believe Iraq posed an immediate threat to the United States, but he still voted for the resolution pushed by the White House. And he expressed hope that Bush would not use this measure to justify racing off to war. “At each pivotal moment, [Bush] has chosen a course of moderation and deliberation, and I believe he will continue to do so,” Biden said at the time. “In each case in my view he has made the right, rational, calm, deliberate decision.”

Biden has since said he regrets this vote. “It was a mistake to assume the president would use the authority we gave him properly,” Biden said in 2005. “We gave the president the authority to unite the world to isolate Saddam. And the fact of the matter is, we went too soon. We went without sufficient force, and we went without a plan.” Today, Biden’s support for the Iraq War could come back to hurt him in a political landscape in which the war is widely seen as a colossal foreign policy error. Sanders voted against authorizing the war—and that’s a point he might well raise as he and Biden face off against each other.

Image credits: Matt Rourke/AP; Greg Gibson/AP; Dino Vournas/AP; Getty