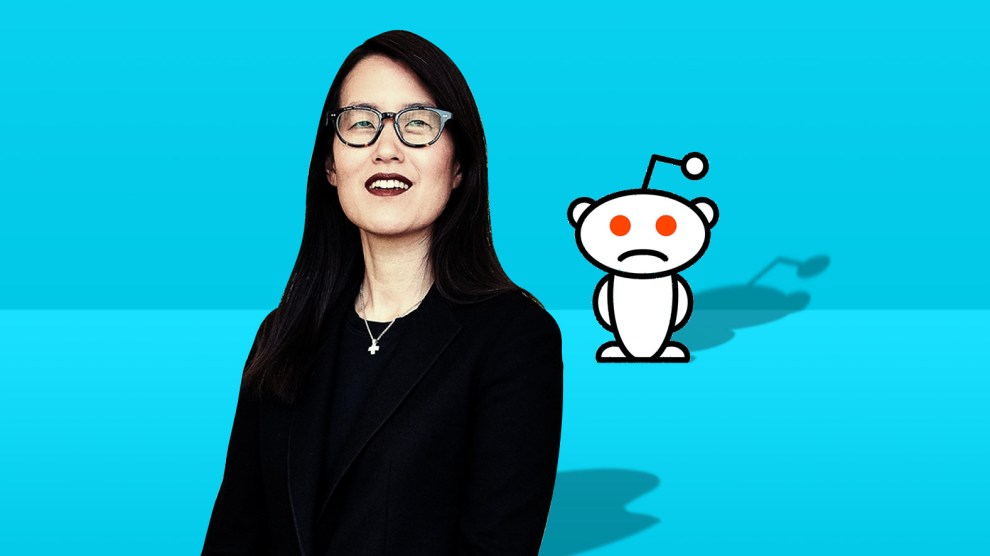

Mother Jones illustration; Courtesy Ellen Pao

Ellen Pao sounds tired. “I actually haven’t been on Reddit in six months,” she says, a remarkable admission for the company’s former CEO. She says she’s tired; tired of her old colleagues’ decisions on hate speech, tired of similar decisions from other social media giants, and tired of being harassed online.

It’s been almost four years since Pao led Reddit. Since then she’s navigated the fallout of an unsuccessful sexual harassment lawsuit she brought that left her ostracized in Silicon Valley circles. When Pao first came forward with her stories of sexual harassment and discrimination at the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, where she was a partner, people, men especially, doubted her claims. She became a pariah at the firm and was attacked online, but her case has come to be seen as a forerunner of the #MeToo movement.

It wasn’t the first time she became a target online, having endured already heavy internet harassment following her decision, just before leaving the company in 2015, to ban some of Reddit’s most toxic subreddits.

Since then, social media companies have taken some steps to address rampant abuse, harassment, and hate that’s proliferated on their platforms. But they haven’t stamped it out to the extent that other types of harmful content have been sidelined.

Reddit continues to struggle with where to draw the line on the popular The_Donald subreddit, home to a xenophobic and sometimes harassing group of Trump supporters, and has been unable to stop abusive behavior like brigading, where groups coordinate large troll campaigns by targeting and infiltrating other communities.

Pao now serves as the CEO of Project Include, a nonprofit that advocates diversity in the technology industry. Even though she’s no longer at an internet company, Pao still has a lot of thoughts on what platforms should do to stop the spread of hate and harassment, and she’s disappointed by how little they’ve accomplished.

Our conversation happened not long after the killings at mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, by a shooter whose internet behavior and manifesto left little doubt he had been radicalized online. Though his writings didn’t make specific reference to Reddit, the site has acted as a bridge between the darker, bigotry-filled recesses of the internet like 4chan and 8chan (where the shooter did post) and mainstream sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. In the wake of the shooting, the worst subreddits hosted hate-filled homages to the shooters.

Mother Jones talked to the former Reddit CEO about how she thinks her previous industry can take the harassment, abuse, and hate speech it’s enabled more seriously. She’s not confident that they will.

Mother Jones: Reddit seems resistant to banning some of the worst types of subreddits on its platform, including ones that have espoused Islamophobia in the wake of the Christchurch shooting. I was curious to get your take as someone who made key decisions to start banning these types of toxic subreddits.

Ellen Pao: Part of it is fear—the fear that platform employees have of their users drives a lot of decision making in ways you don’t expect. My guess is that there’s a lot of fear of people who are running and using The_Donald. It’s not a subreddit that is following the rules or should actually be there. Part of it is usage: It’s hard to take down a subreddit which is driving a lot of traffic.

But at the end of the day, if you don’t follow your rules, you end up having more people not follow the rules. If your platform doesn’t hold people accountable to the rules then your rules really don’t have that much meaning. You see that not just on Reddit, but on Twitter, where people are allowed to break rules because of newsworthiness, which is very vague. People don’t know what that actually means and you end up with more and more vitriol.

MJ: Those arguments are used for things like President Trump’s Twitter even though he’s probably violated a lot of platform rules. Do you think his account is at a worthwhile level of newsworthiness?

EP: From having run a platform, you have to have one standard—otherwise it really doesn’t mean anything. When you see the impact of the words, when you see the impact of the content, and it leads to harassment and you have experienced that harassment, you have a different perspective. It’s not just words. It’s not just speech. It can be very hurtful.

Thinking about the recent suicides among the people from Parkland and the father from Sandy Hook, this ongoing harassment and abuse has an impact on people. I can’t imagine losing someone and having people say “they’re alive” and that I’m a liar as I’m trying to grieve and overcome what is probably the most horrible experience of my life. This should not be allowed, and I do think it contributed to the father’s death by suicide. I can’t imagine that it didn’t.

There is a strong link between bullying, suicide, self-harm, and suicidal behaviors with harassment online. That’s stuff that people have actually researched and proven. So when you’re in charge of a platform and you allow this kind of behavior, I hope these people are holding themselves accountable for what is happening and what is coming out of their platforms. If they really believe the value of this so-called “public square” or so-called “free speech” is worth it, they should understand what the consequences are and be forced to acknowledge that—in the interest of building these platforms, in the interest of generating revenue, in the interest of generating engagement—people are being harassed to the point of where they actually are suicidal.

MJ: These points are good and important, but at the same time, we’ve been having these types of conversations for the last couple of years, especially since people like you have brought these types of issues to light. Are there are new things in this? Are things changing at all?

EP: I can’t tell. I think there is a kind of acceptance of harassment on these platforms now. It’s become so widespread. More people are experiencing it, unfortunately, and you see it on multiple threads. You get into a hate train or trolling and it’s more prevalent, especially in this political environment and in this environment of fake news, people have started to tolerate it more. People are also starting to understand the platforms’ role in it, are seeing Facebook’s problems with Myanmar, its problems with fake news, its problems with allowing holocaust deniers a platform. It was five years ago when the Southern Poverty Law Center wrote about how Reddit was becoming an on-ramp for Stormfront, one of the worst sites for white supremacy. And nobody seemed to really care. I’d think people would really pay attention to a report like that. People would say, “Oh, this is actually really bad.” People know now white supremacy is a huge problem in our country. It’s no longer something we’ve taken care of and that it’s just some fringe groups.

MJ: You’ve talked about how you think these issues are partially being driven by the lack of representation of marginalized people—women, people of color.

EP: I think it’s fascinating that at the largest platforms we don’t have people of color, women of color—and really not very many women—on the boards, on executive teams. I’m sure there are, but I don’t know a single product leader at Facebook who is female. I think there is one or two, but you don’t hear that much about them. You don’t hear about anybody leading anything at Twitter other than diversity and inclusion. The people who have the positions that are making these decisions, like product, like engineering, they’re predominately white men. And that’s true at Twitter and that’s true at Reddit and that’s true at Facebook.

I think that the inability to connect to the harassment, to feel empathy for the people who are experiencing the harassment at this level, prevents them from actually trying to solve it.

MJ: If you were still at Reddit, are there things you would do there? Are there are subreddits or communities you’d be looking to take enforcement action on right off the bat?

EP: It’s hard. I don’t want to be negative about the way things are being run, but this is a different philosophy. For me, it’s about, “Let’s get a clean platform where everybody can have a conversation and actually have a real conversation and not just have as many people shout at each other as possible.” It’s been a long time since you could really go to Reddit and see that conversations were authentic.

If that’s what Twitter and Reddit are trying to have, then you’ve gotta get rid of people who are shouting people out of the public square, who are really bullying people. That’s not a conversation. You have to make sure everyone has the space to speak—and make sure that the speech isn’t causing damage—and that’s not happening right now.

MJ: I’ve noticed brigading going on where you have different people coordinating raids on a different group, stifling conversations.

EP: One way it plays out is one group of bad actors will brigade a set of people, usually on a subreddit, and if your subreddit is being brigaded, you don’t really have the tools to really stop it. Nobody from the company is really helping you, so you end up brigading the other subreddits. The best defense is a good offense. You use those same patterns of behavior to attack the people who are attacking you because you don’t have any other tools. That is the way that it happens. The people who are defending themselves are totally getting punished because they end up being the ones who attack. You end up with this horrible situation where they weren’t initially the bad actors, they’re just trying to defend themselves and they get totally punished by the system. That just happens time and time again, and it’s a terrible experience for everyone. The subreddits are a mess.

MJ: It seems like there’s been a lot of off-platform coordination with this, especially in places like Discord. And this isn’t just a Reddit issue. It’s happening on Twitter, it’s happening on 4chan. How much culpability do you think those types of places have in this ecosystem?

EP: It’s been happening for ages and across platforms. For a while it was a way for people to avoid being banned. The platforms didn’t really consider what was going on on other platforms. They looked myopically at their own sites. At Reddit in 2015, we changed the rule so that offsite behavior was considered in applying the rules, as well as onsite behavior because there was just too much going on that was outside of Reddit and it was super coordinated and it was a loophole. People could do things elsewhere and then brigade a subreddit. Because we couldn’t show that it was coordinated on our own site, we had a hard time dealing with it when it was clear it was happening on Twitter and other platforms—4chan and 8chan especially. It’s not a new thing.

MJ: How do these issues get better? With government regulation? I know people have talked about that a lot in regard to privacy, but does it make sense with content moderation too?

EP: I don’t know. Part of me hopes that the CEOs actually do want to do something about it and it is the fear of their users that limit them—fear of their boards, fear of investors—that prevents them from doing the right thing and keeping all their users safe. Regulation will give them an excuse to take on people and their bad behavior in a way that they wouldn’t have to explain and defend and perhaps they wouldn’t get as much abuse heaped on them, so they kind of have the justification out of their hands.

I don’t think regulators will do it the right way, though. That’s my big reason why I’m not out there pitching it. But we’re at a point where, how could it be worse?

MJ: Is that because you don’t have much faith in Congress as it currently is or because regulators will miss things because they’re not inside these companies?

EP: A little bit of both. We talk about the lack of diversity in tech companies; our government is getting better but it’s not super diverse either. To understand the actual extent of the behavior you’re trying to prevent requires having people from different backgrounds and I don’t know how that’s actually going to happen in the regulatory area. I don’t know though…It’s just gotten so messy.

MJ: You mentioned that you haven’t been on Reddit in six months. Is there a particular reason for that?

EP: I just—I think a lot of it is, some of the content I don’t really trust.

MJ: Was there a period of time when you did trust the information on Reddit more?

EP: Yeah, maybe 7, 8 years ago. But once you see how the sausage is made, it makes you a vegetarian. You see what happens to people. We’ve created this desire for drama and that dopamine rush and that need for conflict that all of our sites are struggling with.

MJ: Are these types of issues your biggest concern for platforms or do you think issues of privacy or something else is more pressing?

EP: Oh man. It’s changed from what I can see, but Reddit, when I was there, we were super, super oriented around privacy. I haven’t had to deal with as many privacy issues because of that. It was easy. We could say ‘Hey, you’re not allowed to share people’s private addresses’ and you’d get rid of a lot of bad behavior there. That was one of the tools people were using—doxxing. That was an easy way to ban people because we have this strong privacy orientation.

Maybe I’m old school, because the things people share and the amount they share, and the detail they share, is something I would never do. There’s so much harassment and people trying to find me that I’m super protective of where I live and what I do. I don’t want to give people a vector to be able to track me down.

I have a slightly different experience and framework. You have these stories of companies being able to track that you’re pregnant. There are these things you’re sharing that you don’t realize you’re sharing. When you do a DNA test to see who your ancestors are and all of a sudden you’ve shared all of your family’s information, I don’t think people understand that. And on Facebook, you’re not just sharing your data, you’re sharing all your friends’ information, it turns out.

MJ: We’re further out from when you were in the spotlight more with your lawsuit and when you were dealing with a lot of harassment. Do you feel like things have ebbed a little bit or is internet harassment still very pressing for you?

EP: Oh, I think it’s so prevalent. You say anything and people are all over you. And you can’t have a conversation because people shut down so quickly. And I don’t blame them. They want to protect themselves, but it’s really hard to have a open-minded conversation with both sides. I think the worst types of harassment are becoming illegal. The fact that revenge porn is no longer allowed, we started that at Reddit. We did it in February 2015. We were the first major platform to ban revenge porn and unauthorized nude photos and then every other platform followed us and now there’s legislation preventing it. It still happens, but it’s to a lesser extent.

People are now more aware of how harassment actually is hurtful and dangerous. I hope that today, what happened to Leslie Jones wouldn’t happen again, but then you look at what people are allowed to say about the Sandy Hook parents and families. Maybe it hasn’t changed. I don’t know. The general perception is that that type of behavior is terrible. But when the platform CEOs allow it and it doesn’t get taken down… the only thing that causes people to take content down is reporters writing about it. That is not a good system.

MJ: Did you have thoughts on the New Zealand shooter? The influence of the internet ran through his manifesto. Do you think that’s a wakeup call for platforms, or do you think these things will persist on fringe sites like 8chan and 4chan, regardless of what these companies do?

EP: I don’t spend time anymore, thankfully, on 4chan or 8chan. I had to for my work at Reddit because of the cross-platform nature of the harassment. And now there’s all these other platforms that came out when we banned a bunch of subreddits. There’s been this philosophy of “If we allow them to flourish under sunlight, we can convince these people and change their minds, or at least we know what we’re up against.” Actually, that was wrong. We actually help these groups and ideas that are antithetical to our values proliferate. We encourage them and give them the spotlight. And they thrive. That is a complete fallacy in the theory of allowing them to stay on your platforms.

They’re just wrong. We haven’t convinced anybody. If anything, we’ve convinced people to join those movements. It’s interesting because I think people are just wrong and we haven’t admitted that yet.

MJ: Do you think there are different ways companies can address toxicity on their platforms?

EP: It would be interesting for people to treat harassment as a real cost of doing business, and to be tracking and to be transparent about all the different things that happen. All of the wrong decisions that were being made. How do we hold people accountable for the bad things happening on their platform so they actually make an investment? We know they have tons of money. We know they have tons of talent. We know they have tons of experience and data. How do we actually get them to take action and how we do hold them accountable other than reporters, after the fact, calling attention to it?

We need to look at what metrics we should be tracking and maybe that’s a way to regulate. Are there metrics we should be tracking around the hate and around the harassment on these sites that help us know if things are getting better or worse and if companies are investing the right amount to prevent this?