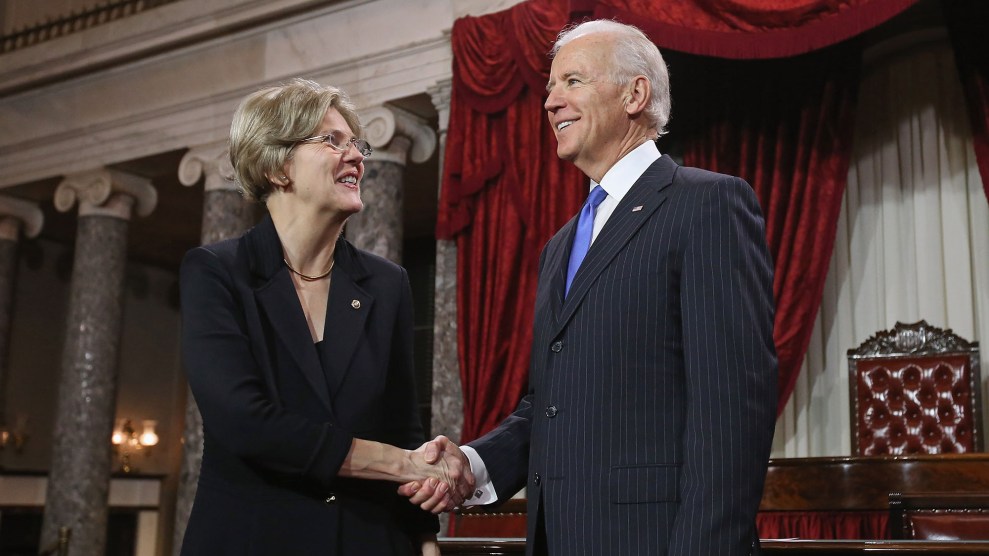

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Just weeks after President Trump appointed him the temporary head of the country’s consumer financial watchdog in November 2017, Mick Mulvaney announced a major personnel change.

When the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was established, its framers took a variety of steps to avoid politicization of its work, including limiting the agency to just one political appointee: the director. But during a press roundtable called to discuss his early days in the job, Mulvaney outlined a plan to bring on a slew of political appointees. He dismissed the idea that the hires represented a significant departure by implying the bureau’s civil service employees, most of whom got their jobs when the office launched during President Barack Obama’s first term, had always been politically motivated.

“I mean, come on now. There’s 1,600 people who work here,” Mulvaney said. “Maybe they didn’t think they needed to have any political people here because a lot of the people here were political, anyway.”

During his yearlong tenure atop the bureau, Mulvaney, who was simultaneously serving as the director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, made good on his plan. He brought in dozens of political hires and installed them in positions where they would keep close tabs on or exercise control over the bureaucratic staffers whose neutrality he had derided. Critics have described Mulvaney’s time at the CFPB, which ended in December 2018 with the appointment of one of his OMB employees, Kathy Kraninger, as director, as having brought a “dangerous” dismantling of the bureau’s power and mission.

Now, documents released under the Freedom of Information Act suggest that highlighting a willingness and ability to kneecap the CFPB may have helped a number of the appointees get their jobs. Resumes obtained by American Oversight and provided to Mother Jones reveal that appointees to senior-level jobs regularly advertised their experience working to weaken the bureau’s authority while seeking positions where they could determine its future.

After earning their jobs, the appointees pushed dramatic changes in the bureau’s work—dismissing congressionally-mandated advisory boards, weakening enforcement efforts, and relaxing payday lending regulations. While the CFPB did not respond to multiple Mother Jones requests for comment on the hires or their CFPB careers, some have gained further stature at the bureau under Kraninger’s leadership.

“If their hiring was based in part on touting a commitment to fight against the work of the Bureau, that raises real ethical questions for me,” says Melissa Jacoby, a consumer finance professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Law. “How is that helping the American public?”

One of Mulvaney’s first political hires was lawyer Brian Johnson, who had long served as an aide to Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas), the then-chairman of the House Financial Services Committee and one of Congress’ most persistent foes of the CFPB. Within a month of taking charge at the bureau, Mulvaney brought Johnson in as a powerful senior adviser in the director’ office, one who would have the authority to act on his behalf as Mulvaney juggled two full-time jobs.

The resume Johnson submitted to the CFPB addressed his years of related work at the House Financial Services Committee. He noted that he conducted “oversight” and “investigations” of the bureau’s spending and highlighted that he had “drafted and assembled several titles of the Financial CHOICE Act, including CFPB reforms.”

The specific “reforms” that Johnson boasted of working on urged changes that would make the CFPB’s consumer protection job harder by mandating a burdensome cost-benefit analysis for proposed rules, weakening a longstanding doctrine that helps the bureau defend its authority when sued, and forcing the CFPB to be funded through the regular congressional appropriations process. (Most financial regulators are funded separately to maintain independence.)

These changes, coupled with the CHOICE Act’s broader package of reforms, amounted to a total gutting of the bureau’s power. The bill would have ended the CFPB’s status as an independent body and made it easier for the president to fire its director. It proposed stripping it of its authority to supervise and examine financial institutions, to enforce laws prohibiting deception by financial actors, or to monitor financial products for risks to consumers. And it would have removed the CFPB’s power to oversee or limit payday lenders, auto financing, or arbitration agreements—all areas where, during the Obama administration, the CFPB brought major reforms. The bill even pushed rebranding the bureau as “the Consumer Law Enforcement Agency.”

While the bill has not become law, in his new job, Johnson helped make one of its original proposals a reality when he was involved in Mulvaney’s controversial February decision to roll back Obama-era restrictions on payday lenders.

Johnson’s resume also emphasized his work developing “strategy, briefing materials, member questions and messaging” for hearings featuring Obama-era CFPB director Richard Cordray. Republican committee members’ questioning of Cordray at such appearances often grew heated as they accused his agency of seeking flashy fines, and of regulatory overreach. Some members went so far as to demand his firing.

Six months into his tenure leading the CFPB, Mulvaney promoted Johnson to the agency’s No. 2 job, acting deputy director. There, Johnson helped implement major changes to CFPB policies and practices, crafting a proposal allowing financial companies to bypass certain consumer disclosures, and authoring a new CFPB five-year strategic plan, which proposed reining in enforcement activities. In May, Johnson was promoted to be the CFPB’s deputy director.

Shortly after Johnson’s appointment, Mulvaney recruited another political hire, Eric Blankenstein, to come on as a senior-level policy director in the bureau’s law enforcement arm, the division of supervision, enforcement, and fair lending.

Under Mulvaney’s leadership, Blankenstein and other political appointees outside of the directors’ office were paired with the senior career officials already heading each of the bureau’s major branches.

“It’s almost like an exoskeleton that’s being grafted onto the infrastructure of the bureau. That didn’t exist back in then Cordray era,” says Chris Peterson, a consumer law professor at the University of Utah who worked in the CFPB’s director’s office from 2012 to 2016. While Peterson says it’s not unusual for the director to seek to bring in ideologically aligned staffers, Mulvaney’s particular structure—one of “parallel appointments with managerial control”—is “unorthodox. I have not seen things done like that at the other banking regulatory agencies.”

Blankenstein was assigned to shadow the longtime associate director of supervision. However, multiple sources told American Banker that Blankenstein was soon effectively in control of the division, whose primary role is enforcing consumer protection laws. In applying for the job, his resume emphasized his time poking holes in the very same laws while doing legal work for banks under CFPB scrutiny. One line on his CV highlighted working at law firm Williams and Connolly, where one of his clients there was TCF Bank.

In January 2017, the CFPB alleged that the Minnesota-based bank had broken two laws enforced by the bureau by tricking more than half a million customers into paying for unnecessary overdraft services and fees. The policy was integral to TCF’s revenue: branch employees were ordered to get 80 percent of relevant customers to sign-up for the services, and got bonuses when they did so. The bank also threw parties when they reached milestone numbers of sign-ups. The bank’s CEO even named his yacht “Overdraft.”

In defending his client, Blankenstein and his colleagues argued that Congress had never intended the laws TCF was accused of violating to be applied to the bank. But they also argued that the entire agency was illegal, and had no enforcement power. “[T]he CFPB is unconstitutional,” wrote Blankenstein and his colleagues. “And because it is unconstitutional, it lacks authority to bring this action.”

“It is awfully cheeky to advertise that you tried to destroy the agency when you’re applying to be in charge of it.” says Peterson. “Then he becomes the most powerful person in the Bureau’s law enforcement division. That is a dramatic change in direction.”

In July 2018, six months after Blankenstein joined the bureau, the case was settled. While Blankenstein was reportedly recused, the terms negotiated by the enforcement division he oversaw were relatively lax given TCF’s more than $24 billion in assets. TCF did not admit or deny wrongdoing, but agreed to pay $25 million to customers in restitution and another $5 million in fines—$3 million to a different federal office involved in the suit, and just $2 million to the CFPB itself. The settlement became an examples of what people inside the agency have reportedly dubbed “the Mulvaney discount”—drastic reductions in fines for corporate offenders. In March, House Democrats questioned CFPB director Kraninger about the practice.

Blankenstein also appears to have taken aim at one the CFPB’s signature Obama-era actions—a multi-billion dollar lawsuit against student loan servicer Navient. The CFPB sued Navient in January 2017 after talks seeking a $1 billion settlement fell apart. But after arriving at the bureau, Blankenstein met with Navient’s CEO and reopened settlement talks while reportedly scrutinizing the suit’s central claims, causing concern among staffers that he would force the enforcement division to close the case on friendly terms.

At the end of May, Blankenstein departed the CFPB following internal backlash after the Washington Post unearthed old blog posts he’d written questioning whether the n-word was racist and calling hate crimes “hoaxes.” The blog posts angered employees working under Blankenstein, many of whom enforce laws protecting against lending discrimination. Last week, Politico reported that Blankenstein has gotten a new job at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, where he’ll work at the general counsel’s office.

The same month that Blankenstein joined the CFPB, so did Hallee K. Morgan, as an attorney-adviser in the director’s office, where she would work alongside Johnson and Mulvaney. Morgan and Johnson had worked together before at the House Financial Services Committee, where Morgan had been a lawyer since 2016. There, Morgan noted on her resume, she had “worked closely with legislative counsel to manage and draft key provisions” of the Financial CHOICE Act, which would have repealed the Dodd-Frank Act and eliminated the CFPB, its keystone reform.

The resume also highlighted her work writing an internal House report rejecting disparate impact theory, which holds that discrimination can happen even if unintended by the lender, and has been the legal underpinning of the vast majority of the CFPB’s lending discrimination cases. Months after Morgan’s arrival in his office, Mulvaney announced that the bureau would reexamine the use of disparate impact in fair lending cases. More than a dozen state attorneys general wrote to Mulvaney pleading against the change. President Trump, meanwhile, signed an order invalidating the use of disparate impact against auto financiers.

Since the arrival of Mulvaney’s appointees, CFPB staffers have warned that the newcomers are damaging the work of the bureau. In August, student loan ombudsman Seth Frotman quit the bureau in protest, writing a scathing resignation letter where he placed blame on the recent hires: “The bureau’s new political leadership has repeatedly undercut and undermined career CFPB staff working to secure relief for consumers,” he wrote. “I was proud to be part of an agency that served no party and no administration; the Consumer Bureau focused solely on doing what was right for American consumers. Unfortunately, that is no longer the case.”

Rep. Maxine Waters, who became chair of the House Financial Services Committee after Democrats took control of Congress last year, has vowed to focus her committee’s work on undoing “the damage that Mulvaney has done.” This spring, she and 30 other democrats introduced the Consumers First Act, a bill aimed at reversing a number of structural changes implemented by Mulvaney at the bureau. The proposal includes limits on CFPB political hires but, in the face of a Republican held Senate and White House, is unlikely to become law anytime soon.

In the meantime, consumer finance experts worry that changes brought by these political hires that have reduced the bureau’s power will not only grow ever harder to undo, but may put the nation’s financial architecture at risk.

“If they are successful in trying to weaken this organization, that’s something that will be felt by American families,” says Jacoby. “As people’s memories of the 2008 crisis fade…it may be helping to create more opportunities for systemic risk again. And that’s going to be on them.”