Courtesy Barbara Lau

Tonight marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising by patrons of a New York City bar against police harassment, an event that triggered the start of the gay liberation movement.

To recognize this pivotal moment in history, former President Barack Obama designated Stonewall as a national monument in 2016—the first of its kind recognizing LGBTQ history. And as far as such historic sites go, Stonewall soaks up all the attention—this anniversary it will be the heart of massive celebrations expected to draw three million revelers to New York City.

But there are other places that map LGBT history throughout the country. Some have achieved official recognition. Some no longer exist. This Pride Month, these ten sites deserve to share the limelight of Stonewall’s big day:

The Black Cat

Before Stonewall, there was The Black Cat, a gay bar in Los Angeles, and the site of a February 11, 1967 uprising—then the largest LGBTQ protest in US history.

The demonstration took place in response to a New Year’s Day police raid, when eight undercover LAPD officers beat patrons and staff. The protests spurred the founding of The Advocate magazine. The Black Cat was designated as a Historic-Cultural Monument by the city of Los Angeles in 2008.

Dr. Franklin E. Kameny House

This two-story, red brick building is where Dr. Franklin E. Kameny lived, and it served as the Washington, DC, headquarters of the Mattachine Society, one of the country’s first gay rights organizations.

Kameny, a WWII veteran, was dismissed in 1957 from his job as an astronomer with the Army Map Service and barred from federal employment for refusing to answer questions about his sexual orientation. His lawsuit contesting the firing went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court; although unsuccessful, his case is considered to be the first civil rights claim based on sexual orientation to reach the high court.

Often called the father of gay activism, Kameny continued to push against discrimination in federal employment and security clearances, and was one of the people instrumental in overturning the American Psychiatric Association’s definition of homosexuality as a mental illness.

Listen to interviews with some of the people who played a major role in LGBTQ history on this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

Congressional Cemetery

Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC, may be the only cemetery in the world with an LGBTQ section.

The private, non-profit cemetery in the city’s southeast was once favored as a last resting place for congressmen and other public officials. Its LGBTQ section started in 1984 when Leonard Matlovich, a gay rights activist and Vietnam veteran, chose to be buried there. His headstone, meant to be a memorial to all LGBTQ veterans, doesn’t bear his name. It reads: “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.” He selected Congressional Cemetery because he knew Arlington Cemetery wouldn’t allow such a marker.

As a kind of last laugh, Matlovich asked for a plot in the same row as FBI men J. Edgar Hoover and Clyde Tolson. Hoover was the first and longtime director of the agency whose anti-gay campaign led to the dismissal of thousands of gay and lesbian employees across the federal government. Tolson was the bureau’s associate director, Hoover’s friend and, according to some historians, his romantic partner.

Route 66

Route 66 was one of the first cross-country highways, spanning 2,400 miles from Chicago to Los Angeles.

Michael Ryan, an amateur historian and the creator of a historic gay bar tour in New York, volunteered to travel from Chicago to Springfield, Missouri, with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, documenting places in communities along the iconic stretch of road that welcomed LGBTQ travelers more than 50 years ago.

Even though many of the LGBTQ sites he researched along Route 66 have closed, Ryan said a queer space is more than just a physical place.

“It’s not about the fog machines and the lights and everything like that. It’s where you learn from your elders. Gay people don’t have the grandparent-to-parent-to-child transfer of knowledge,” said Ryan. “I think queer people have to be much more intentional about finding out their people’s history and customs and rituals.”

Ms. Sid’s Coiffures

Transgender warrior Jody Suzanne Ford was a hairstylist and owner of the fashionable salon Ms. Sid’s Coiffures. The building still stands in the Five Points South neighborhood of Birmingham, Alabama, and is being considered for historical status, according to Josh Burford, historian and director of The Invisible Histories Project.

“There are these stories of these kinds of folks all over the queer South,” Burford said, people like Ford who risked their livelihoods and their lives defending their right to be themselves.

Ford was fatally shot in a Birmingham motel parking lot by the motel’s manager, Larry Clifford Maddox, in 1977. She was 41.

Pauli Murray Family Home

Pauli Murray was a gender non-conforming civil rights activist and architect of some of the most important civil rights victories of the 20th century. Her childhood home in Durham, North Carolina, is now a National Historic Landmark and is scheduled to open to the public next year as The Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice.

“When historians look back at 20th-century American history, all roads lead to Pauli Murray,” says Barbara Lau, director of the Pauli Murray Project. “She was at the nexus of workers’ rights, civil rights, women’s rights, a little bit into LGBTQ rights.”

“Because we simplify things so much we don’t necessarily look at the human beings that are nuanced and don’t fit so carefully into a box, and Pauli pretty much tried all her life not to be in boxes,” Lau says.

Darcelle XV Showplace

Darcelle XV Showplace in Portland, Oregon is home to the country’s longest-running drag club and has a long history of standing up for LGBTQ rights. The venue, bought in 1967 by Walter Cole in a rundown neighborhood, has been a local legend for more than 50 years. The glitzy shows are still emceed by the grande dame herself, Darcelle, Cole’s larger-than-life stage persona. At 89 years old, Darcelle holds the Guinness World Record as the world’s oldest performing drag queen.

When Darcelle XV opened, Oregon still had laws banning gay sex, and LGBT people often felt targeted by police. The venue became a safe space and allowed everyone to be themselves without fear of persecution.

Stonewall Park

In 1983, Fred Schoonmaker and his partner Alfred Parkinson attempted to create a hate-free “gay city” in Nevada known as Stonewall Park, believing that discrimination against LGBT people had reached a point where they would be safer segregated from the straight population.

To promote the idea, Schoonmaker started Reno’s first gay magazine, Stonewall Voice. The couple initially tried to build Stonewall Park in the small desert town of Silver Springs, Nevada. When the project was presented to locals, they vehemently opposed it.

Using money he had inherited after his mother died, Schoonmaker then bought an abandoned ranch called Thunder Mountain. Nevadans organized a petition opposing the site, and then-Governor Richard Bryan went so far as to say most Nevadans wanted to see the city built in another state. Out of money and support, the couple returned to Reno, where Schoonmaker died of an AIDS-related heart attack.

San Antonio Country

In 1973, Arthur “Hap” Veltman transformed a one-story stone building along the San Antonio River into the Texas city’s premiere LGBTQ bar and discotheque. That same year, the state passed a law banning “homosexual conduct.”

Military police often raided San Antonio Country looking for gay service members. Veltman and Gene Edler, co-owner and bar manager, decided to stage a protest play called “Fairies Fiasco,” a campy musical challenging military harassment. Veltman also went to court and demanded the police obtain warrants before they entered his bar—and won.

San Antonio Country remained a queer sanctuary until 1981 when the property was sold to Valero Energy Corporation for their corporate headquarters.

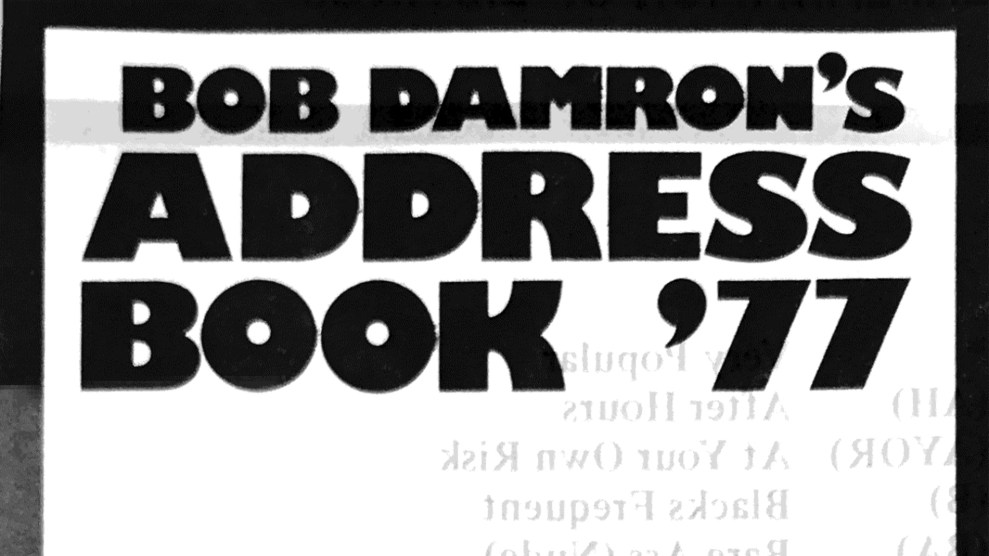

Bob Damron’s Address Book

While not technically a historic gay space, upon its release in 1964, Bob Damron’s Address Book became the first published yearly directory documenting such places—spaces where gay Americans lived, loved, and found solidarity in the face of social and political adversity.

“They’re the only definitive guide that we have to try to recreate this LGBT world that no longer exists,” says Dr. Eric Gonzaba, an assistant professor of American Studies at California State University-Fullerton. “These places are so fleeting.”