AlxeyPnferov/Getty

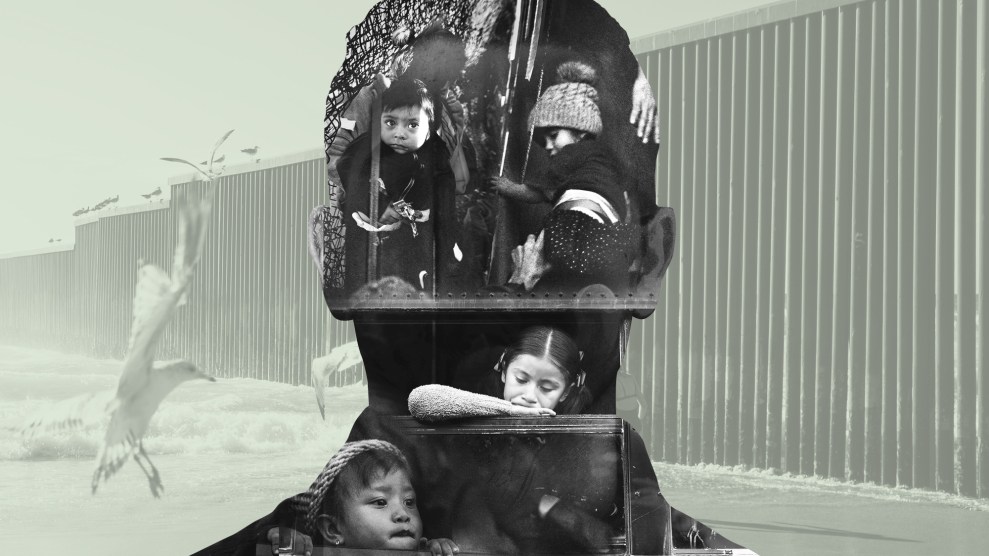

In recent months, migrants at the southern border have endured grim living conditions and forced deportations.

A sobering study led by researchers at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health and published in the academic journal PLOS ONE sheds light on what migrants go through to arrive at the border in the first place.

The study is based on data collected between 2009 and 2015, when more than 12,000 migrants participated in a voluntary survey about their experiences with physical, psychological, and sexual violence during their transit through Mexico. The participants were surveyed at one of five migrant shelters across Mexico, ranging from Tapachula, the country’s southernmost city, to Tijuana, the northernmost. Most of the migrants in the study were Central American men; the average participant had already attempted to enter the United States twice.

Nearly a quarter of participants reported experiencing physical violence, including beatings, thefts, and kidnappings, en route through Mexico. Sexual violence was also rampant: 3 percent of women and 12 percent of transgender individuals reported being raped. One in six transgender participants reported exchanging sex for goods, food, or protection.

Some participants gave harrowing qualitative interviews detailing their experiences. “They said, ‘the deadline [for paying ransom] is over and we’re gonna screw you,'” said a 51-year-old man from El Salvador. “They took off my pants and stripped me. He tried and I resisted.” A 28-year-old woman from Guatemala explained, “The advantage of being a woman is that men will help you just to have sex with you. Just think of it as paying for protection with [your] body.”

The study marks the largest collection of data tallying up violence experienced in transit through Mexico—a process typically described in anecdotal terms. “There has been a lot of sensationalistic reporting and academic work on this stuff,” said Jeremy Slack, a geography professor at the University of Texas-El Paso who studies deportation and violence on the border. “You get a lot of these statistics floating around where you cant find where they came from. There’s something to be said for doing the work and making a conservative estimate that’s more likely to represent the reality.”

Slack attributes much of the violence experienced among migrants in Mexico to the country’s crackdown on human mobility. “When people are really hiding from authorities, the abuse by authorities goes way up—there’s more extortion [and] more organized crime,” he said. “When they allow people to simply buy a bus ticket in southern Mexico [or] fly through Mexico, you could see a relatively uneventful journey.”

This mentality is at odds with the current political reality: Thousands of Mexican National Guard members and other security forces were deployed this summer on the country’s southern border with Guatemala in an attempt to crack down on illegal immigration and stave off tariffs threatened by President Donald Trump.

The study doesn’t capture the current situation at the border, but it was collected during the migrant surge in 2014—and study co-author Cesar Infante said that what he’s heard from the five shelters suggests that the levels of violence haven’t changed much. Infante noted that given the vulnerability of the population and the mistrust of authorities, the numbers were likely an underestimate.