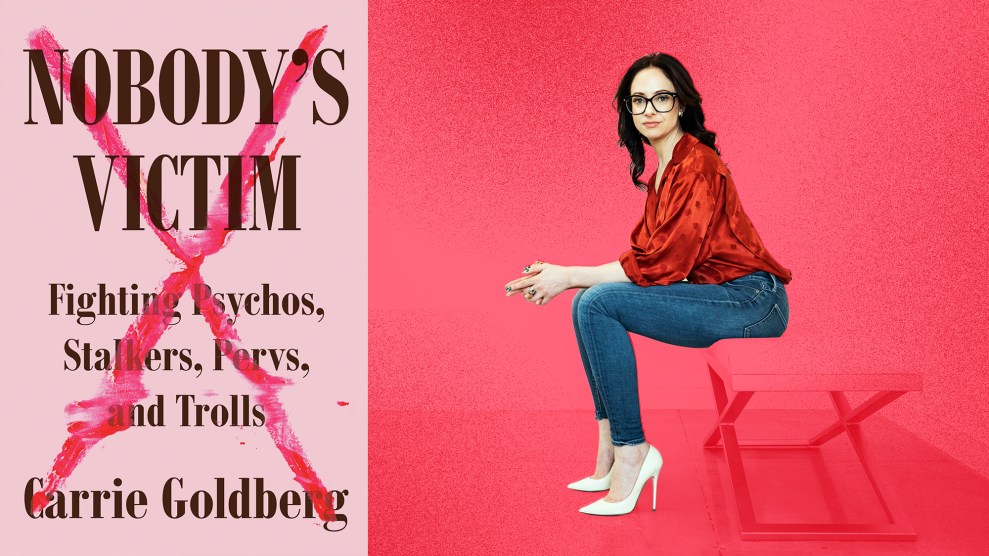

Mother Jones illustration; Natan Dvir

Listen up, assholes. Carrie Goldberg is coming for you.

Since founding her law firm in 2014, the defiant, trash-talking New York lawyer has built a reputation for going after sexual predators from Harvey Weinstein to anonymous trolls and purveyors of nonconsensual pornography. In her new book Nobody’s Victim: Fighting Psychos, Stalkers, Pervs, and Trolls, Goldberg and co-author Jeannine Amber tell war stories from Goldberg’s fight on behalf of clients who have been abused or had their privacy violated online. Interwoven with their stories is an inventory of Goldberg’s tools for taking down bad guys on the internet, from copyright law to brash cease-and-desist letters. (“I’ll be taking over negotiations from here. Negotiations just ended.”)

Nobody’s Victim is a battle cry not just against the various subgenres of abusive men (and they are mostly men) responsible for extorting, threatening, harassing, stalking, or assaulting Goldberg’s clients, but also their enablers—the victim-blaming cops and judges, “chickenshit” school officers, and the tech moguls and venture capitalists who fund and build “the idiot inventions that ruin our lives.” She’s aiming high: Her much-watched lawsuit against the gay dating app Grindr, which she has asked the Supreme Court to review, has the potential to transform the way courts interpret a bedrock internet regulation, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

But the book also revisits the story Goldberg has told about her own origins, that after being stalked by a “psycho ex,” she became the lawyer that she desperately needed. She reveals that she was vulnerable to her ex’s manipulations in the first place because of a devastating date rape that left her psychologically and physically scarred. Goldberg’s year of recovery from the attacks by both men, learning to protect herself but also rediscover a sense of hope and purpose, is the origin of her singleminded focus. “I stopped inventorying the men who had fucked me over. I quit admonishing myself for making stupid choices and bad mistakes,” she writes. “Nothing mattered but the fight.”

I called up Goldberg to talk about the decision to share her own story, her battles against little men and Big Tech, and the differences between living in fear and staying vigilant.

You write that the guys you go after are “as boring and predictable as they are dangerous.” So you use a shorthand to refer to them—they’re either assholes, psychos, pervs, or trolls. Besides the obvious satisfaction of calling an asshole an asshole, how are these categories useful?

Categorizing things is the first step in being able to understand and respond to them. The psychos are the relentless stalkers who have put everything in their own life aside in order to focus on destroying their victim. Usually there’s a lot of anonymizing software that the offenders use. They’re pretty hard to physically locate, because they often have fled the area and are hiding from the law. In those cases, a cease-and-desist letter, lawsuit, or family court order isn’t going to suffice. The only way that they can actually be stopped is law enforcement.

But the cease-and-desist order that wouldn’t work with a psycho might be more useful for a troll?

Especially if they have something at stake. If they have something to lose; if their job or their family would be horrified about their conduct. There are certainly psychos who troll, and trolls who are psychos—you know, it’s a Venn diagram. But if you’re just being trolled, it generally is not as dangerous. It’s just sort of their nighttime hobby.

You write that assholes, psychos, pervs, and trolls are motivated by something similar—“the same impulses that trigger other offenders to drive cars into groups of protestors and fire assault rifles into churches, synagogues, and schools.” What, in your view, is that shared motivation?

A raging need for power and control. It all comes down to some person prioritizing their own right to be in this world—or online—over somebody else’s. We’re just talking about the choice of weapon. Some are going to be using an iPhone to send naked pictures and post them on a website. Others are going to be using a dating app to impersonate somebody and send men to their home expecting sex. And others will be grooming a 13-year-old they meet on a video game into sending sex pictures. There are communities now for people who hate women, are violent, and have access to guns [to] all come and—commune in.

In the manosphere. Sorry, I can’t say that word without laughing.

I’ve actually never said it out loud.

Yeah, I wouldn’t recommend. As a lawyer, there are different ways you could have fought these people. You chose to focus on civil law and making somebody pay, literally, for the harm that your clients have suffered. Why that route?

A lot of people think it’s crude to put a price on suffering. And, of course, it doesn’t undo the harm. But in this world we live in, money buys power. A client, even if she doesn’t want the money, can donate to an organization that fights for the things that she values, or she can donate it to a political candidate. A lot of people are sheepish when it comes to admitting, even when they’re in my office, that, yeah, I want to sue that motherfucker. I want all his money. And I’m like, good. Cause that’s what we’re going to do.

There are a lot of different kinds of work we do where the object is not money—cases where we’re just trying to get a restraining order for our clients, or we’re trying to get that motherfucker arrested, or we’re trying to get that content off the internet. But on the other hand, when it does come to having offenders who can pay, I’m adamant that wealth distribution needs to happen. That includes schools, religious institutions, online platforms, social media companies. If they can prevent it, or if they’re monetizing, in any way, the injuries my client has sustained, then I want them to pay for it.

You’re unequivocal about wanting to repeal Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which has prevented you from making tech companies pay for the way their platforms have been used by abusers. What’s your argument?

It’s a 26-word law that went into effect in 1996, that says interactive computer services are not liable for “information content” provided by a third party. The problem is that over the following 23 years, courts have interpreted that law more and more broadly, so that internet companies cannot be held liable for the activities of their users—even when they know about their harassment, or sextortion or impersonation. It’s outrageous to me that the most omniscient and omnipotent industry in the history of the universe is basically outside the reach of our courts.

The broadest interpretation to date was our case, Herrick v. Grindr, where our client was impersonated by his ex-boyfriend on Grindr, the online gay dating app. He created profiles and then would use the geolocating functions to send strangers to our client’s home and job for sex. He was basically setting up our client to be raped. Grindr was in the exclusive position to be able to stop this, and they refused. They told us that they didn’t actually have the technology to identify and exclude users. So we sued them under product liability theory, saying that they’d released a dangerous product into the stream of commerce. Grindr didn’t even need to plead [that they were protected by Section 230]. The judge just decided that, and dismissed our complaint.

You just asked the Supreme Court to overturn that judge’s decision. If they do decide to take your case, and rule in your favor, would Section 230 go away?

Only our lawmakers could repeal it. But if [the Supreme Court] takes the case, hopefully the outcome would be that they’ve fixed it a little bit. We’re basically saying you can’t just throw these cases out at the earliest possible moment. And then the second thing [we’re asking for is] a bright-line rule about what “information content” means. We’re suing [Grindr] for Grindr’s own conduct, and their own decision making. If that is information content, then everything that a tech company does, basically, is information content.

You have this public persona, as you put it in the beginning of the book, as a “ruthless motherfucker.” Like your fierce Twitter presence, and the swearing, and cease-and-desist letters like the one you put in the book: “I’ll be taking over negotiations from here. Negotiations just ended.”

I know! I actually really used that line.

How does that unusual decorum for a lawyer end up working to your advantage or disadvantage?

I mean, I don’t go onto court and say fuck all the time. But many of our cases involve really, really graphic facts. Quotes from text messages or tweets of our clients being horribly threatened. I want all that stuff to be in front of the judge. I want them to see the gory details. I also feel that being underestimated is a superpower. Corporate lawyers who are defending a tech company are used to dealing with other corporate lawyers—and so I think it’s fun to throw them off.

I can’t imagine the sheer panic if I were to find out if there were intimate photos of me on the internet. But if I did, what should I do next?

Well, I’d say, take a deep breath. Call somebody. Then take screenshots. It’s going to be okay. You’re not the first person that it’s happened to. There’s a huge community of people who’ve been victims of nonconsensual porn. And there are lots of legal tools and advocacy tools that can be used—such as what’s called a DMCA, a takedown notice. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, they all have forms on their platforms to fill out, and bans on revenge porn. Google has a policy where they have the discretion to remove revenge porn from your search results.

You’ve said that the guiding principle of your law firm is that every single one of us is moments away from crossing paths with someone hellbent on our destruction. And in your book, you recommend your clients read another book, The Gift of Fear, by Gavin de Becker, which is about living in a state of vigilance. What does that book mean to you?

The Gift of Fear is all about trusting your instincts, and your body’s physical perception to risky situations. As women, we tend to ignore our own physical responses to things, because we’re trying to accommodate somebody else, or we’re trying to go with the flow, or not cause waves. [When] I was reading that book, I was a few months into starting the firm. It was a revelation for me. I like how it organized the different fear responses that we have. Serial predators are looking for certain attributes and vulnerabilities. The more information that we can all have, the better we are.

One thing I struggle with is the difference between advocating that level of preparation, and victim blaming. As women, we’re used to hearing, Well, why were you drinking so much? Why did you meet him alone? Why would you go out that late? What’s the line between being vigilant—knowing that psychos, stalkers, pervs, trolls are out there and could strike at any moment—and believing that if I’m not taking the precautions to avoid them, then it’s my fault if I’m targeted?

I think it’s really simple. There’s only one party that’s ever going to be responsible for rape, or sexual assault, or stalking. It’s never the victim. I would love for a day to come where I’m put out of business because there aren’t predators and criminals and stalkers. But until that day comes, I want to tell everybody about the patterns, and who they are, and the forms that they take, and the weapons online and offline that they use. Because not only can it help us stay safer, we can pass on information on to our friends. But I know what you’re saying.

So what are reasonable precautions that people should be taking online?

Probably be careful about attributes of wealth. If your online profile talks about you being on the equestrian team and yachting and stuff, you’re going to be a bigger attraction, because you’re easier to blackmail. I think everyone needs to be really careful about sharing where they work, or the industry that they’re in. It’s also true that, when we physically are in somebody’s presence, we pick up on the vibe of the other person. If we’ve exchanged a lot of secrets with a date online, and we have already trusted them with all this intimate information, we’re going to be pressuring ourselves to really like the person when we actually meet. [We’ll] silence any red flags.

You start off the book by telling the neat version of your own origin story that you’ve been telling for years—that you had this psycho ex who started stalking you, and you became the lawyer that you needed to fight him at the time. But then, at the end of the book, you disclose that there was more to the story—including a really traumatic sexual assault right before you met your psycho ex. Would you tell me about coming to the decision to reveal that part of your own experience?

I had no intention of including that story in this book. I had an amazing co-author, Jeannine Amber, who would ask me questions. She kept asking more and more about what state of mind I was in when I met my ex. It didn’t fully make sense to her how I so quickly became controlled by another person. So I sent her this really long email. At the time that I met my ex, I was in a deep depression because of this horrible incident. I told him about it before our first date. It’s exactly what we were talking about—I shared with him all this intimate information about me.

[Jeannine was] like, Well, we have to put this in the book. I was like, Fuck you, no fucking way. This was always the thing that was mine. It’s my secret. And if people know this much about me, will they still want to hire my law firm? I answered my question by looking at all the stories that my clients had trusted me with—the graphic details of the worst things that have ever happened to them. We put that in complaints that are public, we talk about their most private information in courtrooms and sometimes in the media. If they can do that, then why am I not?

I think about this when I write about stories a source, a survivor, has trusted me with. Part of me wants to just make other people stare at it—make them believe this happens, make them react. Because it’s not just an SVU plotline, it’s real.

When you’re telling somebody else’s story you do want to hit somebody over the head with it. But it’s different being on the other side. You want somebody to learn the lessons, but you don’t want them to picture the gory details.

But it would be hypocritical of me to be telling everybody else’s stories, and telling the story of my law firm, without including the most traumatizing part of my story. I also think it’s so good for other people who’ve gone through trauma to know that you can turn that shit into gold. You can learn from it and be fueled by it. Trauma is a burden, but it can also be a gift, if that makes sense.

How do you mean?

I don’t think I would be who I am without the worst experiences that I’ve had. I was a different person entirely before. I was somebody who was content with a middle management job, and wasn’t a leader in my field. But because those incidents happened, they required a lot of affirmative decision making: Get a restraining order. Get protected. There were so many decisions that it’s like I became a new person, forced to trust myself. I stopped being afraid of the things that I had been afraid of my whole life—dumb things like worms, or phobias about speaking in public, or starting a business. I wasn’t afraid to fail. Because it couldn’t have been worse than living in physical fear.

This interview has been edited and condensed.