AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley

For years, the Federal Election Commission has been barely functional. But at the end of this month—as the 2020 campaign heats up and unprecedented amounts of money flow to candidates for national office—much of the agency’s work will shut down entirely. There will be no new fundraising rules, no punishments for rule-breakers, no decisions about the outcomes of investigations, no advisory opinions issued to candidates who want to know if a specific campaign finance practice is illegal.

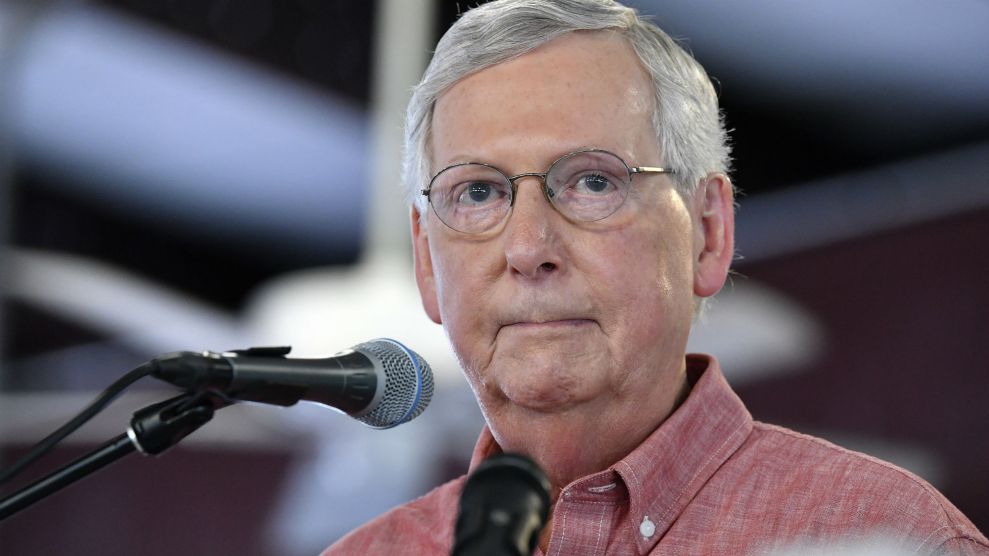

That’s because in order to do any of that, the FEC needs a quorum of four of the six members that, by law, make up the commission. As of September, three of those positions will be vacant. Two seats have been unoccupied for months (since 2017 and 2018, respectively). On Monday morning, one of the remaining Republican commissioners announced his resignation as of the end of the month. There’s little indication that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) will move the fill the empty seats anytime soon.

The lights at FEC headquarters won’t literally go out—campaigns and political committees will still have to file fundraising reports, and the commission’s staff will still post that information information online. But the commission’s leadership will be unable to take any formal actions. New rules will be frozen. Campaigns and political committees will be unable to get advice from commissioners on how to apply rules. And much of the FEC’s oversight activity will grind to a halt. When commission staff conduct investigations of possible violations, it requires votes from the commissioners for any action to be taken on the outcome of those investigations. Similarly, for fines to be imposed on rule breakers, it requires a vote.

Monday’s resignation of Republican commissioner Matthew Petersen leaves one Democrat, one Republican and one independent commissioner. And the timing couldn’t be worse: The 2020 election is predicted to be the most expensive election in history, and a raft of unresolved questions are facing the FEC when it comes to how to enforce rules to keep foreign influence out of American democracy. Rick Hasen, a prominent election law and campaign finance attorney and professor at the University of California-Irvine, said that without a quorum, any chance of the FEC being able to respond to the threat of outside interference is gone.

“With foreign governments and others potentially looking to interfere in the 2020 elections, it is essential we have a working FEC with a full complement of commissioners,” Hasen said. “Even if the Democrats and Republicans on the commissioners would deadlock on ordinary enforcement matters, there is at least a chance they could come together in an emergency to help ensure the integrity of the 2020 campaign.”

At the most recent FEC meeting last week, commissioners punted—for the fourth meeting in a row—on the question of how to attach the same kind of disclosures that appear in television political ads to digital political ads. The commission’s lone remaining Democrat, Ellen Weintraub pressed the other three members to address the issue and complained that she hadn’t been able to get any response from Petersen’s staff.

“I can’t say that I have anything new,” Petersen told Weintraub. “I don’t have a lot to add other than that this particular time I have not been able to develop the formulation I think will bring us to consensus. I wish I had more to say but that is about the extent of it right now.”

Any further discussion on how to increase the transparency of internet ads—on which campaigns are expected to spend as much as $1.2 billion this cycle—was tabled. Thanks to Petersen’s resignation, the tabling will continue for the foreseeable future. Commission members are appointed by the president, and although Trump has made one nomination to the commission since his inauguration, the Senate has not scheduled any confirmation hearings.

Weintraub released a statement Monday afternoon attempting to put an upbeat spin on the news that the commission no longer has a quorum. The agency will continue to take complaints and investigate them, she noted, even if no official action can be taken on the results of those investigations. And, the continued collection of campaign finance reports will still allow the public to monitor money flowing into races.

“I will continue to remain vigilant to all threats to the integrity of our elections—and Americans’ faith in them,” Weintraub said. “But we do need to have a functioning quorum on this Commission.”