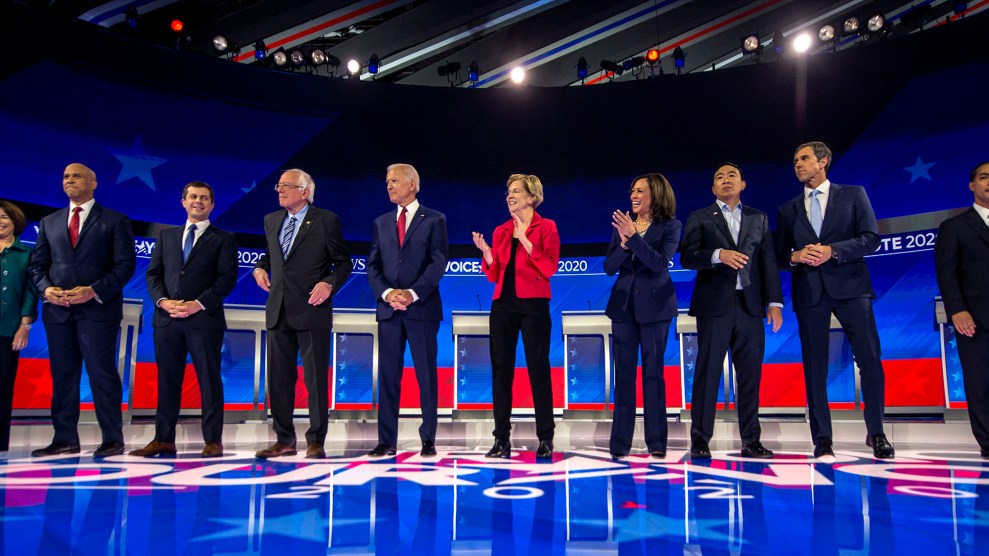

Ten candidates squared off in the third Democratic primary debate in Houston on Thursday, September 12. Brian Cahn/ZUMA

The Democratic presidential contenders spent less time attacking each other on Thursday than in their previous two debates, and more time confronting a different target: the ghosts of their own past stances that haven’t aged well.

The top 10 candidates who shared the stage Thursday embraced a range of progressive policies that were fringe ideas just three years ago in 2016. Some supported buying back assault weapons. Others vowed to support reparations for African Americans. The most progressive defended eliminating private health insurance.

But as the party moves to the left on most major issues, several candidates faced lingering questions about their past positions.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, who leads in the polls, faced the biggest test as he was repeatedly grilled on stances he’s taken over nearly half a century in politics. But his sharpest challenge came on the issue of immigration. Moderator Jorge Ramos asked him to clarify where he stood on President Barack Obama’s record of removing millions of undocumented people from the United States—a record that earned Obama the nickname “deporter-in-chief” among immigration advocates. “Are you prepared to say tonight that you and President Obama made a mistake about deportations?” Ramos asked. “Why should Latinos trust you?”

Biden didn’t answer the question, instead highlighting Obama’s program to allow Dreamers to postpone deportation. When Ramos challenged that Biden hadn’t answered the question, Biden simply replied, “I’m the vice president of the United States.”

Sen. Kamala Harris of California, whose path to the nomination requires winning over many of the more moderate and African American voters now supporting Biden, also faced questions about her past—in her case, as a prosecutor. The senator, moderator Linsey Davis of ABC noted, now supports criminal justice reforms that she opposed as a prosecutor in California.

It’s a question Harris has faced since entering the race, and she came prepared to answer it. “There have been many distortions of my record,” she responded. The reason she became a prosecutor, she said, was to “have the ability to reform the system. I would try to do it from the inside.”

Harris had finally released a sweeping criminal justice platform on Monday that supported some policies she once opposed as a district attorney and attorney general, including ending cash bail and legalizing marijuana. But on Thursday, Harris framed her record as an asset: “Knowing the system from the inside, I will have the ability to be an effective leader and get this job complete.”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota faced similar scrutiny of her record as a prosecutor in Minneapolis. Specifically, Davis pushed Klobuchar on accusations that when black men were killed by cops, she too often sided with the police. Like Harris, Klobuchar was ready for this question. Klobuchar acknowledged a little evolution on this issue: When she was district attorney in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she said, grand juries decided whether to prosecute police officers. Now she believes prosecutors should handle those decisions directly and be accountable for them. Beyond that, she framed her record as one of taking the concerns of the African American community seriously.

The candidates attempted a difficult balancing act between consistency and evolution, authenticity and opportunism—Biden most of all. Throughout the evening, he aligned himself with Obama’s record while distancing himself from policies that are now unpopular among liberal Democrats, like deporting millions of immigrants. Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro, the other Obama administration alum on the stage, confronted Biden on this, prompting Biden to clarify, “I stand with Barack Obama all eight years, good, bad and indifferent.”

It’s not uncommon for a candidate, particularly one with a link to a past administration, to struggle with defining himself in relation to the past. In 2016, Hillary Clinton attempted to champion the successes of her husband’s administration but distance herself from the parts that have fallen out of favor with the party. And Obama’s legacy hovered over the entire evening, from health care to foreign policy. The other candidates struggled with how to both hug and push away the popular 44th president. When the debate kicked off on the issue of health care, nearly all of them stopped to give credit to Obama for the Affordable Care Act before discussing how they would go further to expand access to affordable health care.

This struggle isn’t new, but it seems particularly poignant right now, as the Democratic candidates fall into two general camps: those who promise a more moderate return to a pre-Trump normalcy, and those arguing that today’s problems predate Trump and necessitate bigger solutions and a decidedly different chapter than the past.

Former Rep. Beto O’Rourke, who revamped his campaign message after the mass shooting in his home town of El Paso, named the problem head on when it came to immigration. If elected, he promised to “face the fact that Democrats and Republicans alike voted to build a wall that has produced thousands of deaths of people trying to cross to join family or to work a job,” he said. “That we have been part of deporting people, hundreds of thousands just in the Obama administration alone, who posed no threat to this country, breaking up their families. Democrats have to get off the back foot, we have to lead on this issue, because we know it is right.”

After the third debate, it’s clear that some candidate are still figuring out how to lead on an issue when their past complicates their message.