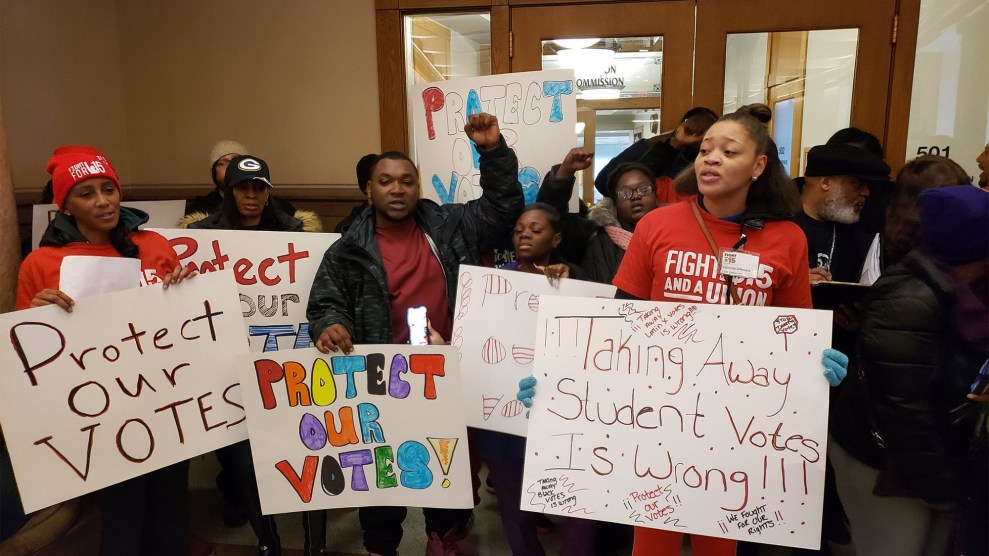

Demonstrators rally at City Hall in Milwaukee against Wisconsin's new voter purge on December 16.Fight For 15/Twitter

Republicans are intensifying efforts to aggressively purge the voter rolls in Wisconsin and Georgia before the 2020 elections, potentially giving their party a crucial advantage by shrinking the electorate in two key swing states.

On Friday, a state judge in Wisconsin ruled that the state could begin canceling the registrations of 234,000 voters—7 percent of the electorate—who did not respond to a mailing from election officials. The Wisconsin Elections Commission, a bipartisan group overseeing state elections, had planned to wait until 2021 to remove voters it believes have moved to a new address. But in response to a lawsuit from a conservative group, the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, Judge Paul Malloy, a Republican appointee, said those voters could be purged 30 days after failing to respond to a mailing seeking to confirm their address.

On Monday night, Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger removed 309,000 voters from the rolls—4 percent of the electorate—whose registrations were labeled inactive, including more than a hundred thousand who were purged because they had not voted in a certain number of previous elections.

These numbers are large enough to swing close elections. Donald Trump carried Wisconsin by 22,000 votes; the number of soon-to-be purged voters is more than 10 times his margin of victory. Democrat Stacey Abrams failed to qualify for a runoff against Brian Kemp in the 2018 governor’s race by 21,000 votes; the number of purged voters in Georgia is 14 times that.

These purges appear to disproportionately affect Democratic-leaning constituencies, including voters of color, students, and low-income people who tend to move more often. In Wisconsin, 55 percent of those on the purge list come from municipalities where Hillary Clinton defeated Trump in 2016. Nine of the 10 areas with the highest concentration of voters slated to be purged voted for Clinton. Milwaukee and Madison, the state’s two most Democratic areas, account for 14 percent of the state’s registered voters but 23 percent of those on the purge list, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

For the past decade, Republican election officials and conservative groups have sought to expand the use of voter purges. They were aided in 2018 by a Supreme Court decision allowing states to remove people who had not voted in two or three previous elections, a move voting rights group said turned the right to vote into a “use it or lose it” privilege.

Both Wisconsin and Georgia have a recent history of inaccurate voter purges based on faulty data. In 2017, Wisconsin sought to remove 340,000 voters who the state government said had filed a change of address with the post office or registered their cars at an address other than the voter registration address. But at least 7 percent of the people on the list had not moved and should not have been on the purge list, according to the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin. Milwaukee removed 44,000 voters but later reinstated nearly half of them, who remained eligible to vote. The state’s new purge list “likely once again contains a substantial amount of unreliable and demonstrably inaccurate information,” according to a legal brief filed by the Wisconsin League of Women Voters. (Because Wisconsin has Election Day registration, purged voters can re-register at the polls, but they need to bring proof of address and a valid ID.)

“If our experience is anything like it was back in 2017-2018, where we lost thousands of voters, we’re afraid that history will repeat itself,” says Neil Albrecht, the executive director of Milwaukee’s Election Commission. “This will lead to people distrusting election administration in Wisconsin. If people feel like a system is rigged, it has a pretty profound impact on whether or not they feel it’s even worthwhile to participate in an election.”

Georgia purged 1.4 million people from 2012 to 2018. That included a purge of more than half a million people in the summer of 2017, the largest in state history. Seventy thousand people purged for having not voted in previous elections re-registered to vote in the 2018 election, and 65 percent of them re-registered in the same county, according to American Public Media, suggesting that they should not have been purged in the first place. Voters living in areas that went for Abrams over Kemp were more likely to be purged.

Earlier this year, the state of Ohio released a list of 235,000 voters slated to be purged. It turned out that 40,000 people shouldn’t have been on it. That included the head of the Ohio League of Women Voters, who had voted in three elections in the past year but nonetheless found herself labeled an inactive voter.

The same sort of problems appear to be resurfacing in the latest round of purging in Wisconsin and Georgia, with eligible voters wrongly targeted for removal.

Some of these voters protested on Monday at City Hall in Milwaukee, chanting, “Protect our votes,” according to the Journal Sentinel:

Sathena Gillespie and her 79-year-old grandmother, Lena Hicks, received notices from the Elections Commission telling them they needed to re-register.

Gillepsie said she doesn’t understand why her grandmother, who has owned and lived in the same home for 20 years, is being asked to re-register.

“My grandmother fought for the right to vote,” she said. “I feel like it’s a slap in the face.”

Felicia McCoats Ellzey, 49, has lived in Milwaukee off-and-on for 30 years. After a recent move back, she said she registered and voted in the 2018 elections.

But like Gillespie, she also received a notice from the commission telling her to re-register. When she responded telling them that she still lives here, they sent the same letter telling her to re-register.

“I guess I’ll have to go and re-register again,” she said.

Fair Fight Action, a voting rights group in Georgia started by Abrams, filed a motion in federal court to stop the state’s voter purge and included statements from voters wrongly included on the inactive voter list:

The actual experiences of Georgia voters confirm that the State’s inactive-voter list includes people who have not moved. Linda Bradshaw has lived at the same address since 2007, last voted in 2017, and nonetheless received notice from the State that she is to be removed from the rolls. Tommie Jordan has lived in the same house for over thirty years, last voted in 2018, and received notice that he is to be removed from the rolls. Deepak Eidnani is in the same position—on the list of inactive voters to be purged even though he has lived at the same address for more than eighteen years and last voted fewer than nine years ago.

While a federal judge declined to block the state’s voter purge on Monday, there will be another hearing on Thursday to determine whether some people wrongly added to the list can have their registrations reinstated.

Wisconsin and Georgia have a history of voter suppression that has affected the outcome of recent elections. Wisconsin’s strict voter ID law kept tens of thousands from the polls in 2016. A University of Wisconsin study found that up to 23,000 voters in Milwaukee County and Madison’s Dane County were blocked or deterred from voting by the law—larger that Trump’s margin of victory—and black voters were three times more likely than whites to cite the ID law as a reason they did not cast a ballot in the presidential race.

In Georgia, Kemp—who oversaw his own governor’s race while serving as secretary of state—enacted a number of suppressive policies that hurt Abrams’ bid to become the first black woman governor in US history. Georgia placed more than 50,000 voters on a suspended registration list before the 2018 election, 80 percent of them voters of color; saw four-hour lines on Election Day in some heavily black precincts; and closed 214 polling places from 2012 to 2018. A new investigation by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that the polling closures kept between 54,000 and 85,000 voters from casting ballots in 2018, with the average voter having to travel twice as far to vote. Voter turnout decreased by up to 2 percent as a result, and black voters were 20 percent more likely than whites to be disenfranchised.

Now voter suppression could once again make the difference in both states. Georgia has two key US Senate elections in 2020, and the presidential race in Wisconsin is expected to be just as close as it was in 2016. A slight reduction in Democratic turnout could be what puts Republicans over the top.