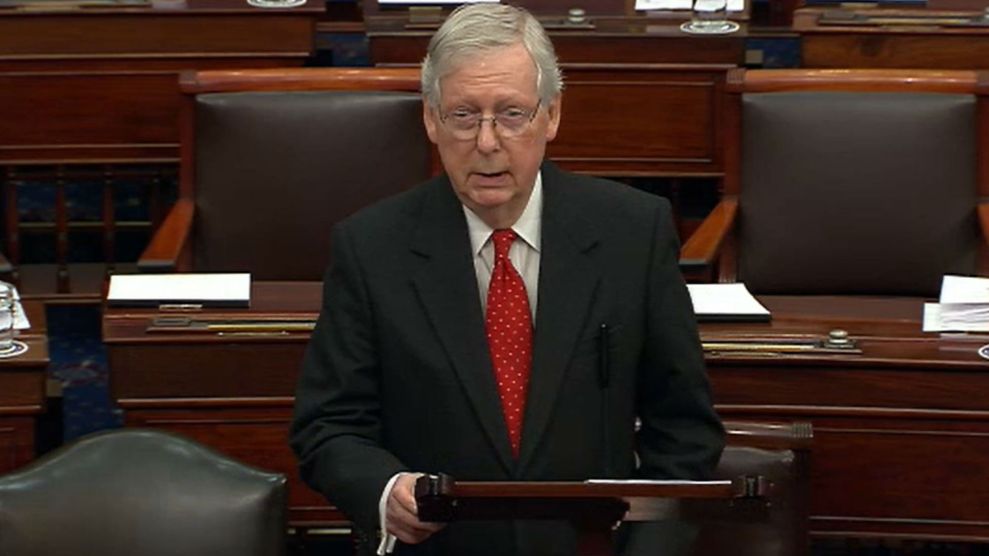

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell speaks during impeachment proceedings on January 21, 2020.Senate Television via Getty Images

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell seems to be testing how rigged an impeachment trial his Republican caucus will allow.

With Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts looking on, McConnell was set Tuesday night to push through rules for President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial that give Republicans the option of acquitting the president without hearing from any witnesses, examining any White House (or State Department or Office of Management and Budget) documents, or considering any evidence revealed after the House voted to impeach.

The course of the trial is not yet fully determined. The impeachment rules expected to be approved late Tuesday night give senators the chance to vote on whether to subpoena witnesses down the road—after up to three days of opening arguments by Democratic House impeachment managers and three days from Trump’s defense team. But the process drawn up by McConnell, who is up for reelection this year in Trump-friendly Kentucky, will give the GOP leader leeway to stave off testimony that might prove damaging to the president and his party.

Democrats derided McConnell’s rules as designed to help Trump cover up his conduct. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer offered a series of amendments on Tuesday that would have altered the rules and immediately allowed subpoenas of witnesses and documents. “This is an obligation we have to the Constitution, to outline what a fair trial would be, to not go along with a cover-up, with a sham trial,” Schumer said on the Senate floor. Republicans rejected amendments pertaining to documents from the White House, State Department, and OMB on party-line votes and were poised to do so for witnesses like acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney.

McConnell’s rules say that the president’s lawyers and the House impeachment managers, not senators themselves, can seek to subpoena witnesses later in the trial. If the Senate votes to allow it, the witnesses “shall first be deposed and the Senate shall decide after deposition which witnesses shall testify, pursuant to the impeachment rules.” This means that the Senate would take multiple votes. It could vote to hear from any of the witnesses Democrats have said should be subpoenaed: John Bolton, the former national security adviser; Mulvaney; Michael Duffy, an OMB appointee who works on national security issues; and Robert Blair, a top Mulvaney adviser. But—and this is crucial—if those officials reveal damaging information on Trump in private depositions, Republicans could then still vote to block them from testifying in public.

The multiple votes give McConnell several chances to block witnesses. Democrats need four Republicans to vote with them to force witness testimony or subpoena documents. (Sens. Mitt Romney of Utah, Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and Lamar Alexander of Tennessee are most frequently cited as potential crossovers, but they’re not the only GOP senators who could buck their party.) By requiring a second vote, McConnell has better odds at prevailing on one or more of those senators. A senator might bow to popular pressure or try to burnish his or her legacy by joining Democrats on an initial vote but then vote to block actual public testimony based on a White House assertion of national security concerns or an executive privilege claim.

The trial rules also give Republicans the ability to avoid considering revelations that came after the House impeached Trump. That includes the Government Accountability Office’s finding that Trump broke the law by withholding aid Ukrainian aid that Congress had already approved, as well as sensational evidence that Lev Parnas, an associate of Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani, recently turned over to the House following a federal court order.

McConnell did show some flexibility on Tuesday. After a caucus meeting in the afternoon, the Republican leader altered a proposal for trial rules he had released on Sunday. The new version dropped a requirement that impeachment managers and Trump’s lawyers present their defense over just two days, a provision that could have pushed proceedings past midnight, but ended them as early as Saturday. (He extended the time frame to three days now.) McConnell also dropped a provision that would have left the House unable to put material it compiled during its impeachment inquiry into the evidence at the Senate trial without a vote. (The altered text still allows Trump’s lawyers to object to adding the evidence to the record by describing testimony as “hearsay” or for any other reason.) Sen. Collins, who faces a tough reelection fight this fall, took credit Tuesday for pushing McConnell to tweak his resolution.

Trump’s lawyers have attacked the impeachment as unconstitutional and unfair but have not substantively disputed the facts of Democrats’ case against Trump. Instead, the attorneys, echoing Trump’s personal pronouncements, assert his conduct was unimpeachable.

Senate Republicans set a course Tuesday to support that argument with limited scrutiny. McConnell’s adjustment to the rules shows that he can still be influenced by public pressure. But the majority leader appears set to tilt as far in Trump’s favor as GOP senators, and American voters, will permit.