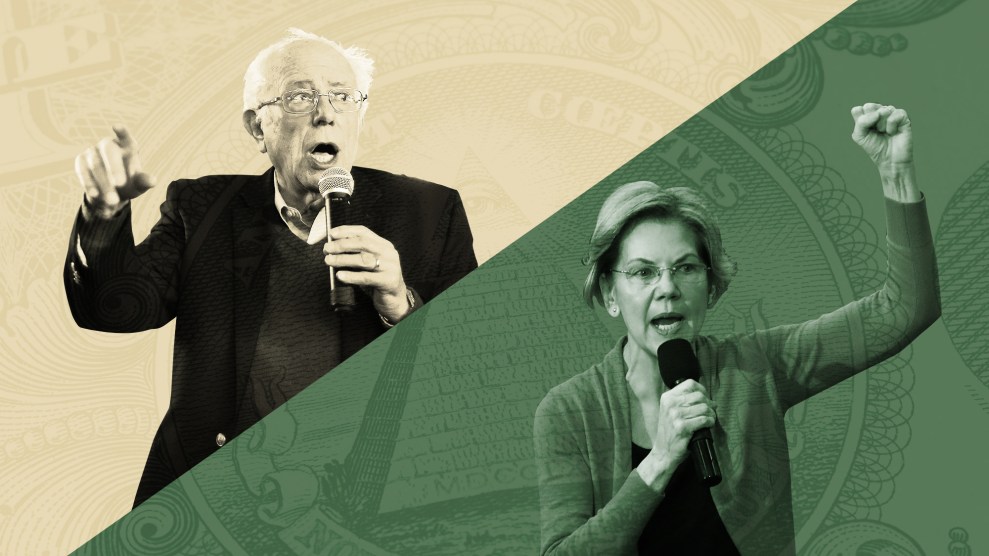

In March 2018, nearly a year before officially putting in for the Democratic nomination, Bernie Sanders hosted a town hall at the US Capitol Visitor Center on the subject of “Inequality in America.” The event promised a lively discussion of “the rise of the oligarchy and the collapse of the American middle class”—lively in large part due to the presence of three people onstage who would soon play central roles in shaping the policy contours of the Democratic presidential primary. There was Sanders, hunched behind the glass table, playing the greatest hits of his 2016 insurgency and railing about “how over $13 trillion in wealth has been transferred from the bottom 99 percent to the top 1 percent” over the past four decades. There was Elizabeth Warren, his 2020 rival, telling her now-familiar story about paying for her University of Houston degree on a part-time waitressing job and lamenting the shift since then in “who this government works for and who it creates opportunity for.”

The third person was a fortysomething man, seated next to filmmaker Michael Moore, in a gray suit with a modest Afro and goatee, furiously scribbling notes as his more famous co-panelists held forth. When Sanders and Warren finished outlining their broad-based remedies for inequality, the man spoke up to offer a gentle correction. “I’d be remiss not to point out that these vulnerabilities are more pronounced for the marginal groups—race, gender, disability status, formerly incarcerated,” he said in a jovial staccato of academese. “They face obstacles the general population doesn’t.” The reason, he said, is systemic racism embedded in government policies that kept Black families from accumulating wealth.

Darrick Hamilton has become the wonk for this political moment because of his talent for quietly reframing the conversation. Now the executive director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State, he has dedicated his years in academia to “stratification economics,” a field of study he helped pioneer that offers structural and sociological explanations for economic inequality as opposed to behavioral or genetic reasons. Hamilton and his longtime collaborator and PhD adviser, Sandy Darity, are largely responsible for the prominence of the racial wealth gap in the discourse surrounding racism and inequality.

At the 2018 town hall, Hamilton rattled off a list of disquieting statistics: There has virtually never been a Black middle class. The average Black household has about 10 cents for every dollar the average white household has. A Black head of household with a college degree typically has less wealth than a white head of household with only a high school diploma. “When Sen. Sanders proposes that we should have tuition-free public education, absolutely!” Hamilton said, referring to Sanders’ College for All Act. “But as an end unto itself. We exaggerate the economic returns on education, particularly for marginalized groups.”

The senators nodded. Hamilton’s reflection invited Warren to preview what would become her campaign’s housing plan, calling attention to how banks had targeted communities of color “for the lousiest mortgages out there.” She recited a history of the gap between white and Black wealth and cited a Boston Globe series that illustrated how Boston’s white households held a median wealth of $247,500, but Black households averaged a mere $8 to their names. Hamilton, grinning, jumped in to tell Warren that it had been he and Darity who had conducted that research.

Over the past two years, Hamilton’s scholarship has made its way from that stage into the bloodstream of the Democratic Party. Several White House hopefuls have turned his research and its policy corollaries into key planks of their platforms, and Hamilton has been a willing collaborator with the campaigns. Warren consulted Hamilton on her housing and higher education plans, seeking advice to counteract trends that have made them unattainable for many Black Americans. Former candidate Cory Booker campaigned on Hamilton’s “baby bonds” proposal, which would give most Americans a government-backed savings account at birth to counteract the wealth gap that persists between white and Black Americans.

Sanders has leaned on Hamilton most of all, not only adding the economist’s federal job guarantee to his campaign platform but also consulting Hamilton on a number of his economic justice policies, including housing, student debt, and education. Hamilton formalized his relationship with Sanders with an endorsement this month, and Hamilton now serves as one of the campaign’s national surrogates. Sanders campaign co-chair Rep. Ro Khanna, who introduced the House version of the job guarantee bill, tells me Hamilton has had a “profound impact on policymakers” and calls him an “intellectual giant of his time,” likening him to Cornel West, another Sanders surrogate.

Darrick Hamilton in Washington, DC, at an event hosted by the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute in April, 2019. (Kevin Wolf/AP)

Despite being the de facto champions of social equality, pretty much every past Democratic presidential candidate since the Johnson administration has shied away from making explicit reference to the ways the government has failed its Black citizens. Instead, a sort of stubborn economism has reigned, both among liberals (remember “It’s the economy, stupid”?) and the left (remember What’s the Matter With Kansas?). This has been a way of eliding so-called “cultural” issues and matters of identity on the mistaken assumption that those things were trivial distractions from the real business of the country, that they could somehow be teased apart from material “pocketbook” concerns of regular people. In his 2016 run, Sanders’ class determinism alienated some Black political activists, who criticized him for not showing adequate support for the Black Lives Matter movement, and perhaps contributed to his weak showing among Black voters in general. In the 2016 South Carolina primary, the Vermont senator won only 14 percent of Black votes.

Things are different this time around. Last year, the Atlantic declared the racial wealth gap “a new litmus test” for 2020 Democratic hopefuls. Politico described the outreach to Hamilton and other scholars as a behind-the-scenes arms race to win the “wonk primary.” Now, many of those candidates who first consulted Hamilton have faded from view—though Sanders, his chosen candidate, is the closest thing to a 2020 frontrunner, thanks in no small part to policies Hamilton played a central role in crafting. The work of Hamilton and fellow economists in quantifying the racial wealth gap has given progressives in the 2020 field a grammar for talking about inequality, one that has long eluded the Democrats. Is the country’s most pernicious division one of class or race? For the first time in more than half a century, the putative party of the worker and of Black rights has begun to figure out where it stands on the question, with Hamilton helping to direct it toward the answer: Yes.

Hamilton began studying economics for, frankly, economic reasons. “I didn’t want to be poor,” he told me. “I didn’t want to be in situations where I had to worry about paying light bills and, you know, bills in general. I thought economics would be a feeder to law school or business school and an economically secure position.”

He didn’t have the luxury of feeling secure about bills while growing up Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant in the 1980s, where he lived among other low-income Black families in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. His father ran a small property management company and served time in prison before dying of AIDS when Hamilton was 18 years old. His mother went to work for New York’s Housing Preservation and Development Agency when her husband went to jail but died when Hamilton was a teenager. Hamilton attended the private, Quaker-run Brooklyn Friends School on a scholarship, an experience he credits with giving him an “ethical orientation towards justice” and sparking his focus on inequity. It also served as a perfect laboratory for examining the haves and have-nots.

“My experience growing up exposed me to two worlds,” Hamilton said. “A lot of friends that I grew up with, versus some of the friends that I went to school with—I could see that fundamentally they are similar people, but one was exposed to a greater set of resources than others, and it influenced their life outcomes. I think the racial dimension [of my studies] related to experiences when it became vivid to me that resources played a lot in stratification.” Hamilton, who has referred to himself as a “scholar-preacher” and “scholar-advocate,” counts as his political idols Jesse Jackson, who ran for president in 1984 and 1988 on a populist race- and class-conscious platform, and William Barber, who leads the “new” Poor People’s Campaign that walks in the footsteps of Martin Luther King Jr.’s original economic justice initiative. “[Jackson] had an economic rights frame grounded in morality, and he had the audacity to run for president with that frame,” Hamilton said. “At an early age, that was influential on me.”

Hamilton was sitting in his old office at the New School, the Greenwich Village university where he taught economics for 15 years before departing for Ohio State. I’d joined him here in this converted Beaux-Arts warehouse, across the street from where Hamilton was shortly due to attend the graduation ceremonies for one of his few remaining PhD advisees. He was dressed for the occasion, wearing a gray suit and orange tie, his Afro and mustache freshly trimmed.

The New School was a fitting place to encounter Hamilton, who first garnered acclaim for his research on stratification economics during his time there. The school had been founded by the Progressive Era’s leading lights who sought “an unbiased understanding of the existing order,” a sharp rebuke to the vulgar inequities of the Gilded Age. That era marked the first rigorous study of the economic status of African Americans since the end of Reconstruction. Foremost among the scholars of the time was W.E.B. Du Bois, who began the work of recasting the failures of Reconstruction as the fruits of sabotage. The story of the Black wealth gap starts there, in fact, with the undermining of the country’s initial attempts at creating the basis for Black wealth generation: Special Field Orders No. 15, the postwar promise by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to grant no more than 40 acres and a mule to the families of the formerly enslaved; and the Freedmen’s Bureau, established by President Abraham Lincoln in 1865 to settle formerly enslaved people on lands that had been captured or abandoned during the war. (There was also the Freedman’s Savings Bank, chartered the same year by Frederick Douglass so that the newly freed could have access to capital.) These initiatives didn’t fail so much as they were failed. As Du Bois points out in his magisterial Black Reconstruction in America, comprehensive land reform was scuttled for the price of the Black franchise. He writes, “[I]ndustry, rather than pay the cost of social uplift on the scale which an efficient Freedmen’s Bureau evidently demanded, would accept immediate Negro suffrage as a preferable panacea.”

During the civil rights era, scholars flocked to the Johnson administration and developed the Great Society programs that birthed a Black middle class. Sociologist Bart Landry later chronicled that development in his book The New Black Middle Class, just as many of the programs that had cultivated that middle class ran straight into the buzz saw of the Reagan administration.

But Black wealth hadn’t been a subject of inquiry until 1995, when Tom Shapiro and Melvin Oliver published Black Wealth/White Wealth, a study of assets—not income—that showed for the first time just how deep the wealth gap ran between white and Black Americans.

At the time, Hamilton was two years into his doctoral work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He picked up where Shapiro and Oliver had left off, raising a number of difficult truths in the process. He found that Black people with lighter skin received better treatment in labor markets than those with darker skin; that the Black infant mortality rate is higher than the white infant mortality rate simply because mothers are Black; that professional-class Black workers face more discrimination than low-wage workers because high-wage Black people pose a greater threat to white workers.

Over the next decade, Hamilton, often working alongside Darity, churned out study after study putting hard numbers behind another difficult truth: Controlling for all other factors, the wealth gap between white and nonwhite Americans could be blamed on race alone. And that gap has persisted because federal policies like the New Deal and the G.I. Bill had systematically excluded Black families from the asset-building activities, like buying a home, that had allowed white families to create generational wealth. The work largely languished beyond the public eye, but the Journal of Economic Literature credited them in 2005 with inventing “stratification economics,” a new field.

One premise of stratification economics is that dominant groups discriminate as a way of preserving status. This might seem obvious, but consider some of the culture’s shibboleths about race—for instance the notion that racism is an irrational expression of chauvinist attitudes. By contrast, Darity has written, “stratification economics presumes the rationality of discrimination, that discrimination is functional in promoting the privileged group’s relative status.” For years liberal politicians spoke of education as the silver bullet for remedying racial inequality. Stratification economics see things otherwise.

“We exaggerate the functional role of education to the detriment of understanding the functional role of wealth,” Hamilton explained. “If I were to unpack that: Because we observe people with high levels of education, perhaps we have the causality wrong—that it was the wealth that might’ve caused the education as much as the other way around.”

His work caught the attention of the Ford Foundation, a philanthropic organization that led the charge to institutionalize Black power during the civil rights movement through grants that established Black studies departments at colleges across the country. In 2006, Ford invited Hamilton to join a group of scholars convened by Ford at the University of California. Two months after President Obama took office, the scholars brought their research to Capitol Hill for a “Color of Wealth” policy summit.

“I knew this issue was going to be one that would capture the nation’s attention at some point,” Kilolo Kijakazi, who oversaw that work at the Ford Foundation, said. “Because of the media attention and the sheer excitement in the room, I thought perhaps it might be in the near term.”

President Obama did talk about the “racial wealth gap.” According to the half-dozen scholars I interviewed for this story, he was the first president who used the term repeatedly, and perhaps the first one who used it at all. But he also had inherited one of the worst financial crises in US history when he entered the White House in early 2009, a crisis premised on predatory lending practices that targeted Black families and wiped out their wealth when the market crashed. Heading into Obama’s presidency, progressives hoped their new president would tackle long-standing issues of economic injustice. Instead, critics say, the administration’s post-recession efforts did little to make those families whole. Worse, executive branch officials seemed to blame those families for their hardship, as Fed chair Ben Bernanke did when he told students at the historically Black Morehouse College in April 2009 that people of color needed to “strengthen their financial literacy.”

“I was in many of those conversations between advocates and the Treasury Department on what to do about the foreclosures,” said Heather McGhee, former president of left-leaning think tank Demos who worked on an Obama administration taskforce that overhauled financial regulations post-recession. “There was no conversation about the racial dynamics that had led to the subprime mortgage crisis and were reshaping wealth and opportunity under their watch.”

What happened next is well-trodden ground. Obama bailed out the banks and instituted a flawed foreclosure relief effort that put the mortgage servicers—those responsible for the disaster in the first place—behind the wheel of the recovery. By the time Obama left office, the Black home ownership rate had hit a nearly 50-year low.

“It was a missed opportunity,” Hamilton said of the administration’s response to the financial crisis. “We could have gone with bolder, more permanent economic policies, and even rhetoric where we weren’t blaming the victims by saying these homeowners engaged in malfeasance and were financially illiterate.”

Across all policy areas, the Obama administration wouldn’t weigh in with remedies that specifically targeted racial inequality. The president’s scholar of choice on these matters was William Julius Wilson, a sociologist whose 1978 book, The Declining Significance of Race, posited that class, not race, was the key factor in determining life outcomes. (Wilson eventually changed his mind, writing in 2009 that officials should explicitly address race in their policymaking.)

Hamilton’s face turned dour when I brought up Julius’ work. “Clearly, the work on wealth is not consistent with that,” Hamilton said gravely. And during Obama’s eight years in power, Hamilton joined a chorus of African American leaders and scholars whom Obama had anticipated would criticize his approach. “The pushback from people in the [Obama] administration would be, ‘I’m naive, I wasn’t in it and didn’t understand all the struggles that were taking place’—and they have said that,” Hamilton said of that time. “I have no idea whether they’re right or wrong, but my response is that from the outside they seemed too cautious, too tempered, and didn’t do enough to change the rhetoric around equality.” Hamilton joined a meeting of Black and Latinx scholars at the White House in October 2010. As he recalled, not much came of it, and to some in the room the effort came off as an attempt to get Obama’s critics to pipe down.

“I think it was his Cabinet,” Darity said of Obama’s unwillingness to pick up their ideas. “There was a judgment he couldn’t win.”

More pernicious than what Obama did or didn’t do, Hamilton said, was a more abstract effect of having a Black president in the White House. To some, Obama’s election symbolized a post-racial society, and the need to push hard against racism abated. “Having the face of power at least symbolically, if not substantively, being a Black person who affirmatively identified himself as Black—that might have delayed some of the importance and relevance around race,” Hamilton said, “because it provided some avenue by which the population could be less mobilized.”

But stratification, inequity, and discrimination continued, to which the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements drew attention in their particular ways. Ta-Nehisi Coates, writing in the Atlantic during Obama’s second term, made the case for reparations, giving popular support to the idea that racism is material and that any redress would have to be material in turn.

The growing concentration of inequality that followed the recession only further underscored the findings from Hamilton and his collaborators: Black Americans were harmed more than their white counterparts when resources grew scarcer. Even without an audience in the White House, the Obama years saw Hamilton and Darity produce their crowning policy prescriptions: They published a paper on baby bonds in 2010 and the federal job guarantee in 2012. Their earliest friendly meetings in Washington were with members of the Congressional Black Caucus. Hamilton recalled meeting with California Rep. Barbara Lee about baby bonds soon after the work was published.

And then, America replaced Obama with a president who represents the epitome of privilege and strives to divide Americans along racial lines, a man once sued by the Justice Department for allegedly discriminating against potential Black tenants.

“Donald Trump has perversely given Democrats political permission to talk about race,” McGhee said. And stratification economics gave them the language to describe it. “The political symbolism of Donald Trump along our continued trajectory towards inequality—I don’t want to use the term ‘silver lining,’” Hamilton paused, carefully choosing his words, “but it might have given us the conditions and platform that allow us to really engage with and work on racial stratification head-on in an explicit way.”

The 2020 Democratic hopefuls haven’t outright criticized Obama’s shortcomings on this front. Swipes, to the extent they’ve been taken, have mainly manifested as attacks on Obama’s former vice president, Joe Biden, a contender who has hid behind his former boss as a human shield for much of his third go at the presidency.

But the adoption of Hamilton’s ideas suggest at least an implicit criticism of the status quo Obama helped to bring about. The calls to Hamilton started coming in early 2018 as would-be candidates began to contemplate the themes of their runs. Booker’s campaign reached out to Hamilton in early 2018. A senior policy staffer had been closely tracking Hamilton and Darity’s work on the racial wealth gap when his boss expressed a desire to do more about wealth inequality. “What drew us to this is a fundamental feeling we should change how federal policy treats people and correct what’s been decades of discriminatory policy,” the former Booker aide said. “There’s a sense that tweaks at the margins aren’t going to do it in terms of creating opportunity for folks who weren’t born into privilege, and a recognition that a lot of federal interventions have very much been focused on tweaking.”

Warren’s campaign also eagerly sought his advice. Hamilton has signed off on a number of her ideas and worked closely with Warren on her policy proposals, notably the ones that, according to the campaign, require “big, systemic change.” Hamilton lent a blurb of praise for her student debt cancellation plan for providing “universal race conscious access” to a college degree.

But Hamilton would later write that “only full cancellation completely protects the vulnerabilities of Black students,” and only one candidate had proposed doing so: Sanders. The candidate has said he’s building an “inclusive, multigenerational, multiracial” movement, and Hamilton agrees. He endorsed Sanders in mid-February, calling attention to his “integrity, values, and policies.”

Hamilton sporadically weighed in on Sanders’ platform during his 2016 run, but a closer relationship developed in early 2018, not long before their March town hall at the Capitol. Stephanie Kelton, a senior economics adviser to the Sanders campaign, was pushing the senator to take up the federal job guarantee, something she herself published research on that year. She invited Hamilton and Darity to meet Sanders in his Capitol Hill office to weigh in. “I wanted him to meet the two of them—I’d admired their work for a long time, and they bring a different perspective,” Kelton said. “What Darrick and Sandy do is remind us there are structural—particularly with racism—problems that a credential won’t solve.”

The group—Sanders, Kelton, Hamilton in person, Darity by phone—worked through the vision of the plan that would eventually be known colloquially as Sanders’ “Jobs for All” plan: How would it be designed? What would the economic benefits be? Darity and Hamilton offered their analysis that a federal job guarantee would significantly reduce the racial wealth gap. “Safe to say that, at the end of the meeting, there was a lot of excitement,” Kelton said.

Over the past two years, Hamilton has routinely received calls from Sanders’ policy team asking him to look through a racial justice lens at various policies it was working on, keeping an eye out for blind spots the campaign might not have identified. While the only Sanders policy that’s substantially lifted from Hamilton’s scholarship is the federal job guarantee, Hamilton has kibitzed on his public education plan, his housing plan, and his proposal to cancel all student debt. “Bernie understands that people like Darrick are attuned to issues and problems that he perhaps is not,” Kelton said. “He wants to hear from everyone: ‘Bring me the ideas, bring me the issues, I’m open to hearing them.’”

Sen. Bernie Sanders listens to a plea from Pamela Hunt of New London County, Conn., a mother with student loans, as he calls for legislation to cancel all student debt in 2019. (J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Along the way, the Sanders team never begrudged Hamilton for consulting with other campaigns. “I asked him if it was okay for me to do that,” Hamilton said. “[Sanders] said, ‘If it’s about making good policy, talk to whoever you want.’”

Darity, who had co-authored a number of the proposals on which Hamilton consults, has opted to operate outside the political area this cycle, preferring to hold candidates accountable in the public sphere. The two no longer work together. “Being an economist for the sake of being an economist has never been enough for Darrick,” Darity said. “He’s far more interested in the prospect of serving directly in a future administration.”

Reparations, in particular, has separated the protégé from mentor. Darity takes a hard line on reparations as the only serious way to reduce the racial wealth gap and rejects other policy prescriptions as insufficient—including some of his own ideas. Hamilton agrees with the need for reparations but prefers to work closely with campaigns to nudge them in that direction, including advising them on what truly would count as reparations and what would not. And Hamilton points to Sanders as the perfect test case. Contrary to campaign optics, Hamilton describes Sanders as a good collaborator, someone who listens well and calls upon folks for a diversity of opinions to help set course. When I asked for an example, Hamilton pointed to reparations: Sanders has recently voiced support for a House bill that would fund the study of reparations, something he came around to through conversations with scholars like Hamilton.

“Some people might see stubbornness, but that’s because his values aren’t ever going to be compromised,” Hamilton said. “But if you show him a persuasive story, he’s persuaded by evidence.”

Four years after Hillary Clinton tried to make hay out of the economism of the Sanders campaign—“If we broke up the big banks tomorrow….would that end racism?”—the Democratic primary has become a sort of rolling seminar in stratification economics and the imbrication of race and class. “I’ve been surprised by the level of depth and honesty in the political discourse,” McGhee said. “Most white people don’t know the degree to which the financial crisis was predicated on racist predatory lending. The policy ideas are important but so is the public education. There’s power in the policy to educate masses of voters in town halls and campaign ads, and that’s what this presidential race has done.”

This is no small feat. Part of the task before the Democrats is to see the origins of Trump’s appeal clearly, to understand the interplay of class and racism and relative status. “A lot of people have argued whether Trump’s base was fueled by economic anxiety or racism,” Darity said. “Stratification economics suggests it’s a false choice. It’s not an either-or proposition. It’s the same fabric.”