People wait on line in to see Sen. Amy Klobuchar in Nashua, New Hampshire.Elise Amendola/AP

Jessica, a 29-year-old elementary teacher, is vexed, highly vexed. She stands in the gym of the high school in Lebanon, New Hampshire, holding her three-month-old daughter. A few feet away, her fidgety two-year-old son is being tended to by Jessica’s mother. Surrounded by Elizabeth Warren supporters who are waiting for the candidate to arrive for a town hall, Jessica can’t make up her mind. And it’s two days before the Granite State holds the first primary election of the 2020 presidential race. “I want to be strategic and vote for the Democrat who can win in November,” she says. And who is that? a reporter asks. “I don’t know,” she replies. “Can you tell me? Please?”

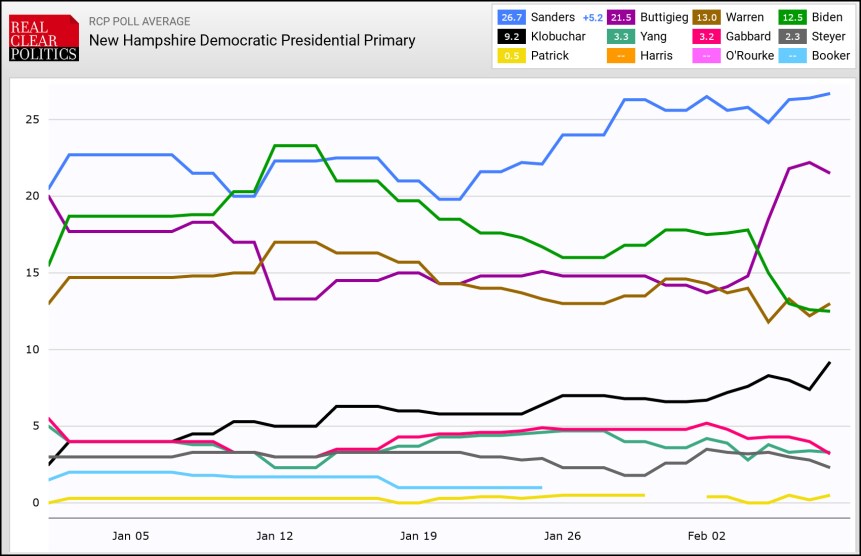

It doesn’t help Jessica to know that a great deal of New Hampshire Democratic voters share her plight. There are certainly many residents who have their man or woman. Rallies for all the candidates are full of committed supporters. But the crowds do contain a significant percentage of voters still struggling. At a Sanders event in Hanover that drew hundreds of Bernie devotees from Dartmouth University, the first row of seats contained not only the candidate’s most fervent supporters but voters, who had arrived hours earlier to be at the front of the line, who were unsure how they would vote on Tuesday. Maybe Warren. Maybe Buttigieg. Maybe Sanders. They hoped that seeing Sanders up close and personal would help them resolve what to do.

Many of the undecideds are driving themselves crazy. They say that they swing back and forth between candidates. It could be Sanders one day, Warren the next, or maybe Buttigieg, Biden, or Klobuchar. And, they report, the choice is a difficult one. That’s because many of them are trying to do the impossible. These still-pondering Granite Staters largely have one priority: removing Donald Trump from the White House. Like Jessica, they yearn to vote for the Democrat who has the best chance of booting Trump. And they believe there is a calculation to be performed that will yield a definitive answer. The problem for them—and the Democratic Party—is that there isn’t. Such an algorithm doesn’t exist.

No candidate in this pack at this point can reasonably claim that his or her case for electability is ironclad—or even far superior than those of his or her rivals. Sanders contends he can both appeal to working class voters who went for Trump and attract voters who don’t tend to vote. Perhaps. But will his standing as a democratic socialist turn away voters and provide Trump an easy line of attack? Pete Buttigieg says he can draw on his middle-America roots to pull in moderates and Republicans. It’s possible. It’s also possible his lack of experience and sexual orientation might be a no-go for general election voters. Joe Biden has the resumé and claims he can appeal to middle-class voters in key swing states. But his performance as a candidate has prompted the obvious comparison to a boxer past his prime. Warren asserts her fight against Washington and corporate corruption can resonate beyond those progressives who have long embraced her as a champion. Yet her failure to stay in the top-tier of the race raises questions. And so on.

There are no political experts—no consultants, no pundits, no pollsters—who can say which of these arguments truly bests the others. It’s all supposin’. Every night at the bar at the DoubleTree Hotel in Manchester, reporters covering the primary gather and compare notes, and no one within this group has much of a better grasp on this question than the voters they talked to that day. The bottom line is clear: There is no one Democratic candidate without an obvious potential flaw. And there is no way to measure the possible impact of these possible flaws ahead of time.

The best one can do is guess. Many New Hampshire voters have done so, and they can tell you why their chosen candidate is the person who has the greatest chance of kicking Trump to the curb. Others are still searching for a clarity that eludes them.

At the Warren event in Lebanon, Doreen Somers, who works at the Dartmouth Medical Center, praised Warren for being “so smart.” But she said she would vote for “whoever can go up best against Trump.” So beyond Warren, she is also considering Andrew Yang and Amy Klobuchar: “Warren could hold her own with Trump, but maybe the other two would be more powerful on the stage.” Joan Beardsley, a retired math teacher, said she wants to know which candidates have studied videotapes of the 2016 debates between Trump and Hillary Clinton. She would vote for that person. Told it’s unlikely any of the contenders have yet done that, she replied, “Then it’s Elizabeth.” She paused and added, “But maybe Bernie.”

David Perlman, who retired from the energy finance business, noted that he spent a long time attempting to determine the candidate most likely to win in November. “I was going nuts trying to figure it out.” Then he realized this was not an accomplishable task. “I stopped doing that,” he said, “and I decided to focus on who inspires me the most and whose ideas I like the most. And then it became much easier.” For him, that candidate was Warren.

The Democratic field offers voters a wide range of choices. But when it comes to electability—a quality that cannot be easily assessed before the fact—there is no ideal candidate. Trump’s presence in the White House has caused many voters to conclude the responsible thing to do is to put aside their own policy or personal preferences to pick a candidate who can trounce Trump. Now if only they knew who that was.