SAN DIEGO IMMIGRATION COURT, COURTROOM #2;

PRESIDING: JUDGE LEE O’CONNOR

Lee O’Connor has been in his courtroom for all of two minutes before a look of annoyance washes over his face.

Eleven children and six adults—all of them from Central America, all of them in court for the first time—sit on the wooden benches before him. They’ve been awake since well before dawn so they could line up at the US-Mexico border to board government buses headed to immigration court in downtown San Diego, Kevlar-vested federal agents in tow. Like the dozens of families jam-packed into the lobby and the six other courtrooms, they’ve been waiting out their asylum cases in Mexico, often for months, as part of the Trump administration’s controversial border policy, the Migrant Protection Protocols.

O’Connor has a docket full of MPP cases today, like every day. Before he gets to them, though, he quickly postpones a non-MPP case to January 2021, explaining to a man and his attorney that he simply doesn’t have time for them today, motioning to the families in the gallery. While he’s doing this, the little girl in front of me keeps asking her mom if she can put on the headphones that play a Spanish translation of the proceedings. A guard motions the little girl to be quiet.

For months, immigration attorneys and judges have been complaining that there’s no fair way to hear the cases of the tens of thousands of Central Americans who have been forced to remain on the Mexican side of the border while their claims inch through the courts. MPP has further overwhelmed dockets across the country and pushed aside cases that already were up against a crippling backlog that’s a million cases deep, stranding immigration judges in a bureaucratic morass and families with little hope for closure anytime in the near future.

I went last month to San Diego—home to one of the busiest MPP courts, thanks to its proximity to Tijuana and the more than 20,000 asylum seekers who now live in shelters and tent cities there—expecting to see logistical chaos. But I was still surprised at how fed up immigration judges like O’Connor were by the MPP-driven speedup—and by the extent to which their hands were tied to do anything about it.

Once O’Connor is done rescheduling his non-MPP case, he leans forward to adjust his microphone, rubs his forehead, and starts the group removal hearing. The interpreter translates into Spanish, and he asks if the adults understand. “Sí,” they say nervously from the back of the courtroom. O’Connor goes down his list, reading their names aloud with a slight Spaniard accent, asking people to identify themselves when their names are called. He reprimands those who do not speak up loud enough for him to hear.

O’Connor, who was appointed to the bench in 2010, is known for being tough: Between 2014 and 2019, he has denied 96 percent of asylum cases. He explains to the migrants that they have the right to an attorney, although one will not be provided—there are no public defenders in immigration court. O’Connor acknowledges finding legal representation from afar is difficult, but he tells them it’s not impossible. He encourages them to call the five pro bono legal providers listed on a sheet of paper they received that day. The moms sitting in front of me have their eyes locked on the Spanish interpreter, trying to absorb every bit of information. Their kids try their best to sit quietly.

As he thumbs through the case files, O’Connor grows increasingly frustrated: None of them has an address listed. “The government isn’t even bothering to do this,” he grumbles. The documents for MPP cases list people’s addresses as simply “Domicilio Conocido,” which translates to “Known Address.” This happens even when people say they can provide an address to a shelter in Mexico or when they have the address of a relative in the United States who can receive their paperwork. “I’ve seen them do this in 2,000 cases since May,” O’Connor says, and the Department of Homeland Security “hasn’t even bothered to investigate.” He looks up at the DHS attorney with a stern look on his face, but she continues shuffling paperwork around at her desk.

O’Connor picks up a blue form and explains to the group that they have to change their address to a physical location. The form is only in English; many of the adults seem confused and keep flipping over their copies as he tells them how to fill it out. O’Connor tells them they have to file within a week—perhaps better to do it that day, he says—but it’s unclear to me how they could follow his exacting instructions without the help of an attorney. He points out other mistakes in the paperwork filed by DHS and wraps up the hearing after about 45 minutes. The families don’t know that’s typical for a first hearing and seem perplexed when it ends.

O’Connor schedules the group to come back for their next hearing in five weeks at 8:30 a.m. That will mean showing up at the San Ysidro port of entry at 4:30 a.m.; the alternative, he says, is being barred from entering the United States and seeking forms of relief for 10 years. “Do you understand?” he asks. The group responds with a hesitant “Sí.”

The Trump administration designed MPP to prevent people like them from receiving asylum, and beyond that, from even seeking it in the first place. First implemented in San Diego in late January 2019 to help stem the flow of people showing up at the southern border, the policy has since sent somewhere between 57,000 and 62,000 people to dangerous Mexican cities where migrants have been preyed upon for decades. Their cases have been added to an immigration court that already has a backlog of 1,057,811 cases—up from 600,000 at the time when Obama left office—according to data obtained by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

According to immigration judge Ashley Tabaddor, who spoke to me in her capacity as union president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, MPP has constituted a fundamental change to the way courts are run. DHS, she says, is “creating a situation where they’re physically, logistically, and systematically creating all the obstacles and holding all the cards.” The MPP program has left the court powerless, “speeding up the process of dehumanizing the individuals who are before the court and deterring anyone from the right to seek protection” All this while the Department of Justice is trying to decertify Tabbador’s union—the only protection judges have, and the only avenue for speaking publicly about these issues—by claiming its members are managers and no longer eligible for union membership. Tabaddor says the extreme number of cases combined with the pressure to process them quickly is making it difficult for judges to balance the DOJ’s demands with their oath of office.

Immigration attorneys in El Paso, San Antonio, and San Diego have told me they are disturbed by the courtroom disarray: the unanswered phones, unopened mail, and unprocessed filings. Some of their clients are showing up at border in the middle of the night only to find that their cases have been rescheduled. That’s not only unfair, one attorney told me, “it’s dangerous.” Central Americans who speak only indigenous languages are asked to navigate court proceedings with Spanish interpreters. One attorney in El Paso had an 800-page filing for an asylum case that she filed with plenty of time for the judge to review, but it didn’t make it to the judge in time.

As another lawyer put it, “The whole thing is a fucking disaster that is designed to fail.”

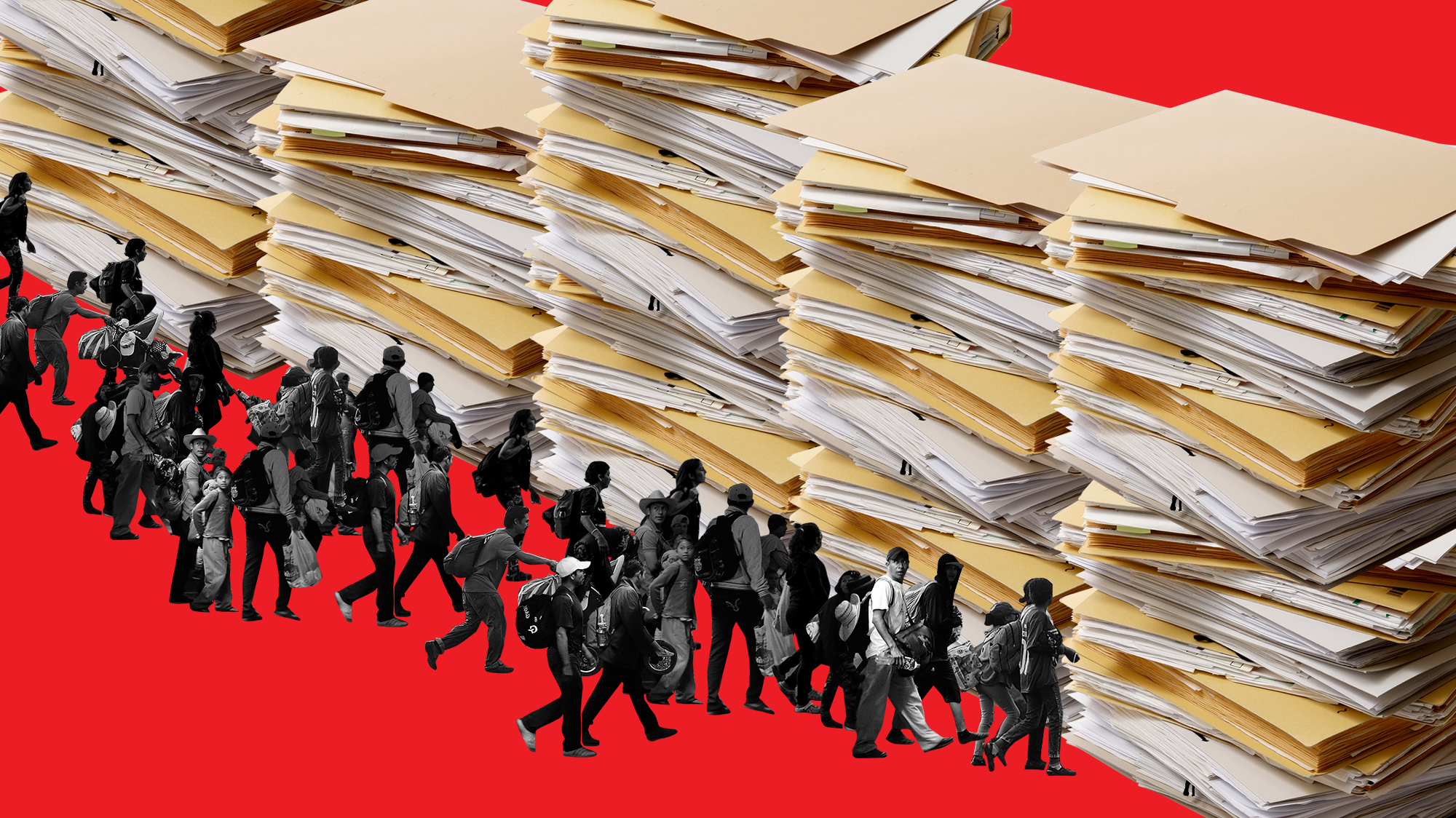

People line up at the San Ysidro border crossing in Tijuana in May 2019.

Guillermo Arias/Getty

COURTROOM #4; PRESIDING: JUDGE PHILIP LAW

Down the hall, a Honduran woman I’ll call Mari stands up next to her attorney and five-year-old son, raises her right hand, and is sworn in.

Mari’s hearing isn’t much of a hearing at all. Stephanie Blumberg, an attorney with Jewish Family Service of San Diego, who is working the case pro bono, asks for more time because she only recently took the case; Judge Philip Law says he will consolidate the cases of mother and child into one; and he schedules her next hearing for the following week at 7:30 a.m., with a call time of 3:30 a.m. at the border.

Just as it’s about to wrap up, Blumberg says her client is afraid to return to Mexico. “I want to know what is going to happen with me. I don’t want to go back to Mexico—it’s terrible,” Mari says in Spanish, an interpreter translating for the judge. “I have no jurisdiction over that,” Law says. “That’s between you and the Department of Homeland Security.” Law then turns to the DHS attorney, who says he’ll flag the case and “pass it along.”

While nine families begin their MPP group hearing, Mari tells me back in the waiting room that she and her son crossed the border in Texas and then asked for asylum. They were detained for two days and then transported by plane to San Diego, where she was given a piece of paper with a date and time for court and then released in Tijuana. She didn’t know anyone, barely knew where she was, and, trying to find safety in numbers, stuck with the group released that day. Two days after US immigration officials sent her to Tijuana, she was raped.

Mari’s voice gets shaky, and she tries to wipe the tears from her eyes, but even the cotton gloves she’s wearing aren’t enough to keep her face dry. I tell her we can end the conversation and apologize for making her relive those moments. She looks at her son from across the room and says she’d like to continue talking.

“I thought about suicide,” she whispers. “I carried my son and thought about jumping off a bridge.” Instead, she ended up walking for a long time, not knowing what to do or what would happen to them because they didn’t have a safe place to go.

“I haven’t talked to my family back home—it’s so embarrassing because of the dream I had coming here, and now look,” she says. “We’re discriminated against in Mexico; people make fun of us and the way we talk.” Her boy was already shy but has become quieter and more distrusting in recent months.

In the last year, I’ve spoken to dozens of migrants in border cities like Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana who share similarly horrific stories. Human Rights First has tracked more than 800 public reports of torture, kidnapping, rape, and murder against asylum seekers sent to Mexico in the last year. A lawsuit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, Southern Poverty Law Center, and Center for Gender and Refugee Studies is challenging MPP on the grounds that it violates the Immigration and Nationality Act, and the “United States’ duty under international human rights law” not to return people to dangerous conditions.

“The system has not been set up to handle this in any way,” says Kate Clark, senior director of immigration services with Jewish Family Service of San Diego, one of the groups listed on the pro bono sheet Judge O’Connor handed out earlier in the day. They’re the only ones with a WhatsApp number listed, and their phones are constantly ringing because “it’s clear that people don’t know what’s going on or what to expect—and they’re in fear for their lives,” Clark says. Still, her 8-person team working MPP cases can only help a small percentage of the people coming through the courtroom every day.

Later that afternoon, shortly after 5, two large white buses pull up to the court’s loading dock. Guards in green uniforms escort about 60 people out from the loading dock. Moms, dads, and dozens of little kids walk in a straight light to get on a bus. They are driven down to the border and sent back to Tijuana later that night.

A few days later, Mari’s attorney tells me that despite raising a fear of retuning to Mexico in court, US port officials sent Mari back to Tijuana that night.

Fernanda Echavarri

Fernanda EchavarriCOURTROOM #2; PRESIDING: JUDGE LEE O’CONNOR

I find myself back in O’Connor’s courtroom for his afternoon MPP hearings. This time, the only people with legal representation is a Cuban family who crossed in Arizona in July 2019 and turned themselves in to Border Patrol agents. This is their first time in court, and their attorney calls in from out of state.

Right away, O’Connor wants to address a different kind of clerical error from the one that bothered him earlier in the day—and one that he thinks matters even more. It involves the first document that DHS issues to “removable” immigrants, known as a Notice to Appear (NTA) form. Although the form allows agents to check a box to categorize people based on how they encountered immigration officials, O’Connor points out that in this case it was left blank—and that “this is fairly typical of the overwhelming majority of these cases.”

He isn’t the first or only judge to notice this; I heard others bring up inconsistent and incomplete NTAs. Border officials are supposed to note on the form if the people taken into custody are “arriving aliens,” meaning they presented at the port of entry asking for asylum, or “aliens present in the United States who have not been admitted or paroled,” meaning they first entered illegally in between ports of entry. Thousands of MPP cases have forms without a marked category. As far as O’Connor is concerned, that’s a crucial distinction. He believes that this Trump administration policy shouldn’t apply to people who entered the country without authorization—meaning countless immigrants who applied for MPP should be disqualified from the get-go.

In the case of the Cuban family, like dozens more that day, the DHS attorney filed an amended NTA classifying them as “arriving aliens.” O’Connor points out is not how they entered the United States. The DHS attorney is unphased by the judge’s stern tone and came prepared with piles of new forms for the other cases of incomplete NTAs. The family’s lawyer says maybe the government made a mistake. O’Connor, unsatisfied, interrupts her: “There was no confusion. I’ve seen 2,000 of these…the government is not bothering to spend the time.” After a lengthy back-and-forth, a testy O’Connor schedules the family to come back in three weeks.

O’Connor’s stance and rulings on this issue have broader implications. He terminated a case in October because a woman had entered the country illegally before turning herself in and wrote in his decision that DHS had “inappropriately subjected respondent to MPP.” He is among the loudest voices on this issue, saying that MPP is legal only when applied to asylum-seekers presenting at legal ports of entry—though it’s unclear to many lawyers what it might mean for their clients to have their cases terminated in this way. Would these asylum seekers end up in immigration detention facilities? Would they be released under supervision in the United States? Would they be deported back to their home countries?

Since MPP cases hit the courts last March, asylum attorneys have been critical of DHS for not answering these questions. I was present for the very first MPP hearing in San Diego and saw how confused and frustrated all sides were that DHS didn’t seem to have a plan for handling these cases. Now, almost a year later, little has changed.

Tabaddor, the union president, tells me that “there are definitely legal issues that the MPP program has presented” and that judges are having to decide whether the documents “are legally sufficient.” “The issue with DHS—frankly, from what I’ve heard—is that it seems like they’re making it up as they go,” she says.

Last week, Tabaddor testified in front of the House Judiciary Committee and for the independence of immigration courts from the political pressures of federal law enforcement. There are approximately 400 immigration judges across more than 60 courts nationwide, and almost half of those judges have been appointed during the Trump era. (According to a recent story in the Los Angeles Times, dozens of judges are quitting or retiring early because their jobs have become “unbearable” under Trump.)

California Democrat Zoe Lofgren, an immigrants’ rights supporter in Congress, argued during the hearing that the immigration courts are in crisis and the issue requires urgent congressional attention. “In order to be fully effective, the immigration court system should function just like any other judicial institution,” she said. “Immigration judges should have the time and resources to conduct full and fair hearings, but for too long, the courts have not functioned as they should—pushing the system to the brink.”

Asylum seekers in Tijuana in October

Guillermo Arias/Getty

COURTROOM #1; PRESIDING: JUDGE SCOTT SIMPSON

“I don’t want any more court,” a woman from Guatemala pleads just before lunchtime. “No more hearings, please.”

Unlike many of the people who were there for their first hearing when I observed court in San Diego, this woman has been to court multiple times since mid-2019. No matter how hard she tried, she couldn’t find a lawyer, she tells Judge Scott Simpson. She’s had enough.

“We’ve reached a fork in the road, ma’am,” Simpson says in a warm, calm tone. “You either ask for more time for an attorney to help you or you represent yourself.”

“No, it’d be a loss since I don’t know anything about the law,” the woman responds, her voice getting both louder and shakier. Simpson explains to her again the benefits of taking time to find an attorney.

“It’s been almost a year. I don’t want to continue the case. I want to leave it as is,” she tells him. After more explanation from the judge, the woman says she’d like to represent herself today so that decisions can be made. Simpson asks what she would like to do next, and the woman says, “I want you to end it.”

This woman’s pleas are increasingly common. Tabaddor says MPP has taken “an already very challenging situation and [made] it exponentially worse.” The new reality in immigration courts “is logistically and systematically designed to just deter people from seeking or availing themselves of the right to request protection,” Tabaddor says.

After hearing the Guatemalan woman ask for the case to be closed multiple times, Simpson takes a deep breath, claps his hands, and says there are four options: withdrawal, administrative close, dismissal, or termination. He explains each one, and after 10 minutes the woman asks for her case to be administratively closed. The DHS attorney, however, denies that request. Simpson’s hands are tied.

The judge tells the woman that because DHS filed paperwork on her case that day, and because it’s only in English, that he’s going to give her time to review it, because “as the judge I don’t think it would be fair for you to go forward without the opportunity to object to that.” He schedules her to come back in a month.

“MPP is not a program I created,” he says. “That decision was made by someone else.”

Additional reporting by Noah Lanard.