Steven Bonnell sighed deeply. “You a bitch-made motherfucker,” says a woman’s voice coming from his computer. “You are retarded,” it continued.

Bonnell, who livestreams his life under the pseudonym Destiny, was in the middle of a debate that had gone way off the rails. The woman, a lower-profile conservative internet figure, had been slated to talk with him about police brutality, but the plan was thrown after she got mad that he called her an “anti-vaxxer.”

As she lobbed insults, Bonnell hardly raised his voice. “I don’t know if I’ve ever debated a smart conservative,” he says to me, turning away from his computer in frustration as she kept up a monologue.

Bonnell is a professional video game streamer who makes his living broadcasting nearly constant footage of himself, usually talking politics, playing video games, debating people, or some combination of the three.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Politically, he’s an outlier. Gaming spaces have a reputation for incubating online right-wing culture, most famously exhibited by Gamergate, the sprawling reactionary harassment campaign that began by targeting women working in gaming, spurred by their presence in the industry and the increased diversity of its products. Like any troll, Bonnell loves an argument, and his battles with the online right have earned him hundreds of thousands of dollars. He regularly spends up to 16 hours a day championing largely left positions, streaming to thousands of viewers at any given moment. Video game streaming is a new public square, and Bonnell has built one of its bigger soapboxes.

When I visited him in his Glendale, California, apartment, the wiry 31-year-old with an Edward Snowden beard-and-glasses combination had woken up just in time to grab a hot chocolate from a nearby Starbucks before beginning to stream around noon. He sometimes doesn’t finish until early the next morning, with little to no break, often not consuming more than a single meal in the process.

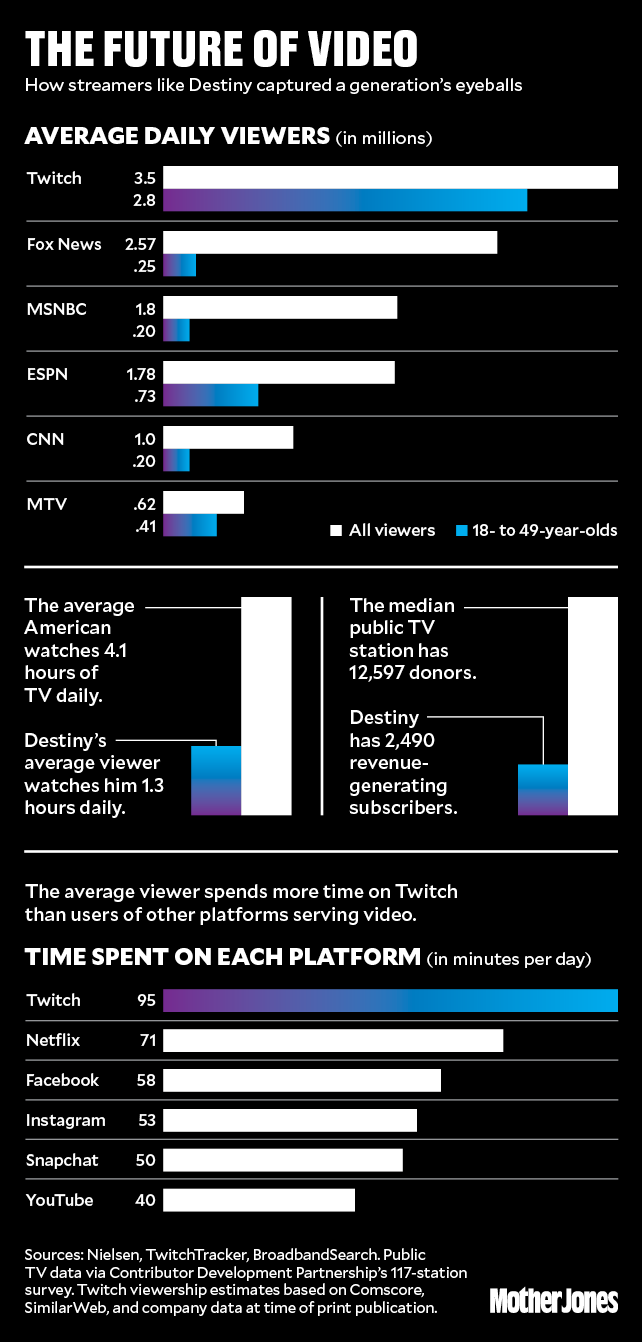

His video is shared on Twitch, the most popular gaming livestream platform, where many have built lucrative careers. Amazon, which ranks the almost nine-year-old site as one of the world’s 50 most visited websites, acquired it in 2014 for $970 million. Every month, more than 2 million people use it to stream, while 15 million watch daily, making it one of the largest online spaces that most people over 30 have probably never heard of.

With people shuttered in their homes with nowhere to go and little to do during coronavirus lockdowns, many streamers have seen increases in their viewership and fanbases, according to SullyGnome, a Twitch analytics site. While most streamers’ individual viewership numbers have followed an upward trajectory predating the virus, across the platform April’s viewership represented a roughly 71 percent increase from February, according to TwitchTracker. Twitch broadcasters have also been streaming more: from February to March, the number of hours users streamed on the platform jumped from 37 million to 49 million.

For the uninitiated, Twitch is sensory chaos. A running chat scrolls across the stream, while stray, ambient noises accompany spontaneous graphics announcing things like new premium subscriptions. Twitch streamers often sell viewers the ability to interrupt their broadcast with pop-up text or spoken messages; Bonnell charges a $5 minimum for the privilege. If a streamer is playing a game while filming themselves, they’ll either split the screen or superimpose their image over the action. Things only get messier when streamers invite colleagues to join in.

Bonnell’s particular Twitch niche is debating conservative internet personalities and staking out mostly progressive positions. That makes Bonnell an exception on the platform and, more broadly, in gaming, where, if anything, people tend to skew toward libertarianism. These gamers have provided recruits for the right wing; Bonnell’s work lays out a different path.

“It feels unfair to paint the entire site with a broad brush in terms of political belief, but I would say in general, the chat probably breaks a bit further to the right. And it feels like the chatrooms and most of the large streaming content, even in video games, break a bit to the right as well. I usually describe it as ‘gamer bro politics,’” Bonnell says. While they may be “middle-class white straight males who call themselves a liberal or Democrat in America, they don’t want to see too many black people in video games…They think Gamergate is good commentary on sociopolitical issues today—so like feminism is ruining media.” This crowd can sometimes be outright bigoted or, at best, ignorant of the adversity that women and religious, ethnic, and racial minorities face. They’ve also been influenced by high-profile online right-wingers—the people Destiny targets.

By intentionally cultivating the sense that he doesn’t care about anyone’s opinions of his opinions, especially regarding what he can or can’t say, he echoes the rhetorical trappings of firebrand libertarians and conservatives. Bonnell’s harshness is probably part of what makes him so popular: His ability to speak the language of Gamergate goes far in an ecosystem that was shaped by it and that has shaped him.

In 2017, he boosted his profile by debating Lauren Southern, a prominent white nationalist. Southern had cited a Harvard economist’s work on immigration and the US labor market to argue for closed borders, but Bonnell came armed with research showing the professor disagreed with her conclusions. As things started to go poorly for Southern, she made her first of many pivots from economics, instead warning of “people creating Shariah zones” that would “change the culture of a country.”

“I don’t know what you mean by cultural problems. I hear crazy statements like ‘immigrants are going to outnumber us,’” Bonnell responded, arguing that migrants tend to assimilate unless they experience discrimination. Southern flipped back, claiming they drain welfare systems and hurt economies. Bonnell cited Germany, which experienced five years of GDP growth alongside the arrival of Syrian refugees, and pointed out many of them want to return once it’s safe.

“They won’t. Why would you go back to the Middle East if you could live in Germany on welfare?” Southern asked.

Bonnell was fed up. “You know everyone’s goal in life isn’t to live on welfare?” he pressed. “These are actually human beings that have their own dreams and aspirations.”

When Bonnell started streaming in 2011, he identified as a libertarian with right-of-center social beliefs. He also spent more time talking about a broader range of subjects—not just gaming, but philosophy and science, along with some politics. While Bonnell says his transition from his older views and topics was gradual, he can point to several catalysts: noticing the harassment a female friend faced when gaming; hearing a friend use an anti-gay slur; and seeing the backlash when the FIFA soccer video games prominently featured a nonwhite player. By the time Donald Trump was making his way through the 2016 Republican primaries, Bonnell’s transformation was complete. He was fully focused on using his stream to foster “better conversations about politics” while tilting the discourse of gaming to the left.

Destiny now identifies as “a very big social democrat” but also as a capitalist. (The latter label, in a familiar online dynamic, can irk his viewers who are further to the left.) He argues that structural racism is real, that the trans community is ignored and underserved, that significant numbers of refugees and immigrants should be welcomed, and that unbridled money has corrupted politics. Some of the frustration he draws from ostensible allies is driven by the language he uses, but also by the fact that he sees himself as having arrived at his positions through a different and “particular paradigm” from most on the left.

“I want to maximize good outcomes for everybody. From that position, I get to things like universal health care, or guaranteeing food and housing and stuff to people, and caring about LGBT issues and racial issues and everything. But I’m not intrinsically attached to that,” Bonnell said, describing a style of argument that foregrounds an obdurate rationality common to online libertarians—which makes sense, given that he identified as one not long ago.

Though Bonnell is virtually unknown in the mainstream, he’s carved out an unusually large following to become one of Twitch’s more prominent personalities; with over 500,000 followers, and 10,000 viewers on his best days, he’s among the most popular Twitch streamers. While he mostly debates right-wing streamers with smaller followings, his prominence has enabled him to take on increasingly high-profile opponents, including white nationalists like Southern and Nick Fuentes.

With the exception of his beloved high-performance Ford Focus RS, Bonnell seems to barely spend the money he’s made streaming. The sparseness of his apartment and the fact he is online most of the day would appear to confirm that. The spartan lifestyle reinforces the impression that he prioritizes his work. “I enjoy the conflict. I love arguing with people and I like it when people hate me,” Bonnell says.

Even if money and luxuries aren’t his focus, they aren’t out of mind. “If you compare me to my family, I easily live the poorest,” Bonnell told me, recalling his childhood in a “huge house” in Omaha, Nebraska, with an indoor pool. That lasted until he was almost a teenager, when his mom’s lucrative around-the-clock home day care business fell apart.

After that, his family’s house was foreclosed on and they bounced around Omaha. “I went from like very upper-middle-class to kind of…desperate,” he said. The experience has made him “super careful” with money. He says it wasn’t until he attained financial security that he understood what he’d gone through or what it said about hardship in America: “I wasn’t aware of how fucked that struggle was until I was on the outside of it.”

Though he never formally practiced as a debater until he started streaming, Bonnell spent time on a conventional path to success. He attended a prestigious Jesuit high school, Creighton Prep, on a work-study program, and boasts of taking Advanced Placement classes and acing the act test before enrolling at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, in 2007 and studying music. But a job as an overnight manager at a casino overtook college, and he dropped out to meet its demands.

He was eventually fired from the job, and after draining his savings, he took up work as a carpet cleaner and began dabbling in streaming the popular real-time strategy game StarCraft. He soon did the math and realized he could make more by streaming games than steaming rugs. In 2011, the first full year he focused on it, he estimates he made $100,000.

Around that time, Bonnell and his partner had a baby. They eventually separated, but not before their relationship came to feature violence on both sides. (They both say they’re now on decent terms, and Bonnell still sees his son.) While recently defending another streamer accused of domestic violence, Destiny spoke about his own history; a clip of him saying, “You better fucking believe that I had to choke her out a couple times,” was removed from YouTube, after I asked him about it, due to a copyright complaint from Voddity, a streaming services company employed by Destiny. He said he was “being hyperbolic” in the clip, but added, “I’m way more chilled out than I was when I was 22.” “My life is very fucking easy,” he told me. “That’s the nice thing about being rich—I have a million options to deal with any problem ever. There’s no reason for me to ever get violent or have a violent encounter and like a domestic situation. When you’re poor, everthing’s way fucking harder. You don’t have another place you can go.”

Sensing “more opportunities” among Los Angeles’ concentration of streamers and gamers, Bonnell moved to Glendale in December 2018, setting up a workstation in the middle of his lofted two-story living room with a west-facing view of the Santa Monica Mountains. He films himself with a camera set on top of one of his two monitors. His desk, illuminated by photography lights, holds a gaming mouse, keyboard, and professional-grade microphone. There’s a couch behind him, and propped in a corner are paintings by his girlfriend, Melina Goransson. A small amount of clothes, a pillow, and other household items are strewn around, with no apparent homes. Flanking his streaming setup is an electric guitar and a keyboard. While he says music is his hobby, he admits he hadn’t played in months, in favor of chasing new viewers and subscribers.

In fact, in the days we were together, he didn’t do much of anything besides stream. Save for leaving once to see some friends he and Goransson met through Twitch, Bonnell didn’t go further than the Starbucks or a ramen place, both just across the street. He doesn’t always even go that far. On a Saturday night, when we decided to grab food, we went to a pizza place inside his apartment complex.

When I finally stood up for dinner after sitting, as he had, for about seven hours, my groin ached in a way that I had only felt on lengthy road trips. Bonnell hadn’t eaten or drunk more than a bottle of water all day, and he’d gone to the toilet just once. This all seemed difficult and unhealthy, which I told him.

“I don’t know. I don’t have to go to the bathroom that much, I guess,” he said, nonplussed, as he, Goransson, and I walked to the restaurant. “I try to only eat one or two meals a day so I don’t gain a lot of weight. I don’t move around a lot, so my caloric burnage every day is really low,” he added, grabbing his stomach. It appeared to be working. He is around 5-foot-8 and pretty skinny despite his extremely sedentary life.

“We’re down to 5,500 now,” Bonnell said as we sat down. In the 10 or so minutes since he had left the stream to get food, his number of viewers had shrunk by at least 2,000. Fewer viewers means less money because there aren’t as many eyes seeing ads. According to Bonnell, there’s also a snowball effect. “When you get more viewers,” he says, “people want to pile on. When you lose them, people get disinterested.”

So streamers feel pressure to stay online as long as possible. Each second they don’t is lost money, which makes Bonnell less likely to travel, leave home, or even pee.

He says he’s “physically lucky,” and he likens his endurance to the natural advantages brought by swimmer Michael Phelps’ massive hands, which propelled him through water, or former NFL quarterback Johnny Manziel’s size 15 feet, which made him a more elusive rusher. “I don’t get sore. I never suffered from like an RSI, a repetitive strain injury,” he says in a way that makes it seem like he has at least weighed the risk.

Aside from his physical advantages, Bonnell is a rapid-fire speaker and thinker. On Twitch, he has the quick cadence of a practiced high school policy debater, along with an air of superiority and dismissiveness that makes it look like he always has the upper hand.

“Destiny is a very skilled orator,” the progressive streamer Hasan Piker says, “even if he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

Critics of debating far-right internet figures have warned of its potential to give platforms to hateful ideologies and challenged its limits to change minds. Personalities like Charlie Kirk, Stefan Molyneux, and Ben Shapiro have taken advantage of the form to make their right-wing ideologies look better with confident rhetoric employed strategically. All three have a record of squaring off against students or inexperienced debaters, who mean well but are no match.

“The efficacy of debate is questionable. The general consensus is that debate at this point is a blood sport and showmanship,” says Josh Citarella, an artist who researches and writes about political trends taking place on the internet’s fringe.

Bonnell admits his doubts about the format that’s helped make him. While he says he first got serious about political debating “to bring people into more fact-based discussions,” after spending years on Twitch, he concedes that airing his opinions on the platform sometimes feels “like screaming into the void.”

Unlike mainstream audiences, most of Bonnell’s viewers are probably already aware of the internet’s most high-profile racists, which might make amplifying their ideas in debates less of a concern. But it has also been good business. “Every debate is a chance to get in front of new viewers. You never know who’s going to be your next subscriber or who will become a huge donor,” he explains. Bonnell says he makes $300,000 to $400,000 each year from Twitch, merchandise, donations, and other sources.

For some viewers, his debates may be the first time they’ve seen right-wing ideas exposed to adept scrutiny. For all his frustrations, Bonnell says the feedback he gets helps him feel like he’s at least slightly moving the needle to the left.

In at least one real way, he is. Academics and journalists have faulted YouTube’s suggested videos algorithm as an agent of radicalization. Users who start watching comparatively innocuous right-leaning content will soon be served videos from white nationalists expounding on immigration. Citarella says Bonnell’s archived debates on YouTube with such figures can end up in those viewers’ suggested videos lists, offering a counterweight that modestly ameliorates the platform’s worst tendencies. “The real utility is the cross-pollinating between content adjusts the algorithm that points you a few degrees to the left,” he says.

“Destiny was basically the sole left-liberal, neoliberal person who was trying to clean up this community for a very long time,” Piker told me when I visited him in his West Hollywood living room. “That’s why I reached out to him originally, to form an allegiance there, and it was very helpful. It definitely helped my growth.”

Like many people trying to make a living online, Piker has worn several hats—political Twitch streamer, commentator at The Young Turks, Instagram influencer. While we spoke, his giant pit bull with a silver chain collar wandered around our feet. We were being watched by thousands. As tends to happen when hanging out with Bonnell, my interview with Piker turned into him also interviewing me for his Twitch audience. I suspected that each one’s willingness to include me was as much a chance for fresh content as it was a courtesy.

One problem with making your life public for eight-plus hours a day is that you provide a lot of material to your enemies. Because of his profile outside of Twitch, Piker stands to lose a little more from these types of bad-faith draggings than most streamers, but the issue is common. In June, while Piker criticized Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s centrist politics, people in his chat pushed back, accusing him of sexism. Piker, in both frustration and irony, joked, “Yeah, I fucking hate women. How about that?” Conservative influencers immediately ensured that an out-of-context clip of the quote spread quickly. It was eventually shared by one of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s sons.

“The beautiful thing about having hours and hours to talk about my opinions is that people in my community know exactly what my position is. And also they are loyal and they’re dedicated,” Piker says. “But in the long term, for mainstream recognition, it is terrible because no one’s going to fucking watch me for eight hours to understand the intricacies in my opinions. They’re just going to see a clip.”

Of course, streamers often make problems for themselves, by advocating or saying indefensible things that justifiably upset people. Bonnell’s critics have assembled some of his worst on-stream moments and spread them around YouTube and Twitter; the clip of him discussing being violent with the mother of his son was brought to my attention by one such person after I spent time with Bonnell.

During my visit, he was navigating another self-inflicted and high-profile controversy. In 2018, Mychal Ramon Jefferson, a streamer who goes by the name Trihex and who is well known for his skill as a speedrunner—someone who beats video games as fast as possible—appeared with Bonnell on a podcast. Jefferson, who is one of Twitch’s most prominent black political creators, and Bonnell teamed up in defense of Black Lives Matter, sparking a friendship. They went on to launch and co-host their own podcast and regularly stream together. But their relationship frayed last October, after Bonnell instigated repeated debates with followers and friends over his belief that there was nothing wrong with white people saying the n-word in private.

Things came to a head while I was visiting Bonnell during the final round of a Rajj Royale, a four- to six-hour debate on a range of topics between almost a dozen streamers moderated by the streamer Rajj Patel. The audience voted one contestant off in each round until only two, Bonnell and Jefferson, remained.

“It hit me kind of hard—I’m not going to lie to you, Destiny,” said Jefferson, describing how he felt about his friend’s insistence that he didn’t care if people knew that he used the n-word in private. “I wish I had a more objective way to frame that, but just in terms of feelings…To me, that wasn’t cool.”

Bonnell initially replied kindly but soon transitioned into a cold rebuttal. “I’m not willing to make the concession that every single thing I make in a private joke should be okay with every other single person,” he responded. “If I go upstairs right now and nobody is listening to me and I say the n-word, I am not causing anyone any harm.”

They tensely went back and forth, and in the final moments Jefferson offered an apology. “I’m sorry. Maybe I’m the one who made this emotional,” he said, looking down sheepishly. Bonnell responded, saying he was sorry for his demeanor.

Bonnell and Patel recognized Jefferson as the winner without an audience vote. But Patel secretly ran one anyway, which showed that 80 percent of viewers agreed Jefferson had come out on top.

Still, it didn’t feel like he won. Watching them debate took me back to arguments I’ve had with my white friends about race. You don’t expect them to fully get it, but you do expect them to desperately want to try. If they don’t try, it can be more disheartening than overt racism from unequivocal bigots, because you hoped for more.

“I felt devalued as a friend. I was emotional,” Jefferson later told me on the phone. “It wasn’t until I cried and I slept on it that the next day I was able to process it.” After the exchange, Bonnell and Jefferson put their podcast on hiatus. Piker, too, distanced himself from Bonnell over the topic.

Most of the time I was with Bonnell, even when we spoke, I stayed out of his camera’s view. But after his debate with Jefferson, I probed him about it, and he had me sit on the couch behind him, effectively turning our conversation into another on-stream debate.

Bonnell had previously paired descriptions of his ongoing imbroglio over the n-word with lucid and self-aware observations about the racism black people face that he glides past as a white man; in one such on-the-record conversation he said the word to me while pressing his case.

Now, he ceded no ground. And as we went back and forth, the appeal of streaming, beyond the money, began to make sense. There was something intensely gratifying about feeling like you confidently argued your points before an audience of almost 10,000 people. It was easy to forget how that power could be used to spread toxic ideas.

While empathy is generally part of caring about social issues, Bonnell favors a certain self-centered intractability that can come off as an offensive disregard for doing anything on anyone else’s terms. When I asked him if he considers himself an ally, often defined as someone with privilege who takes on the struggles of disadvantaged groups, he immediately said, “Fuck, no.”

Citarella says that much of the streaming world favors this style of argumentation. “People who have grown up on this stuff came up from a rational skeptic, libertarian worldview,” he told me. “That aesthetic level of the debate really resonates with them.”

When I asked Bonnell if he thinks he’s benefited from stylistically resembling online right-wingers, he affirmed without hesitation: “Oh yeah, definitely.”

“I’ll never make an appeal in the way a lot of liberals would, like ‘We should allow more immigrants just because you should have compassion for people, guys.’ I would never do that shit. I don’t give a fuck about health care being a human right,” Bonnell said scornfully. “I always rely on stuff like ‘Well, here’s what the empirical data says about immigration’s impact on the economy.’ What I care about is that we have people that die when they could have health care, and it drains the fuck out of our economy.”

“People like Destiny are from these communities,” Citarella said. “They don’t feel like outsiders who are coming in with content to shill. They have the appearance of being trustworthy, independent rational thinkers, which appeals to these majority-young, majority-white men.”

That familiarity with the gaming community goes far. “Destiny’s name is thrown around with relative reverence compared to anyone else. There’s a certain respect for Destiny in these circles. He’s an anomaly. There kind of isn’t anyone like him,” Citarella said.

T.L. Taylor, an MIT professor who studies video games and gamer culture, thinks that point of view is frustrating and unjustified. “Destiny is not the only person on Twitch pushing back on horrible Trump policies and the alt-right. What’s unfortunate is if the rest of the [gaming] world thinks Destiny is the only person doing this,” she said. “He gets treated as an anomaly. It really flattens and erases others who are lefty feminists and people of color on Twitch.”

While the shock-value of Bonnell’s edgelord tendencies is key to his on-camera presentation, IRL he can be softer. The first time I left his apartment, he had the idea we should hug each time we say goodbye, though he seemed slightly uncomfortable with it. While Goransson seemed to vibe with her boyfriend’s boundary pushing—I once saw him playfully target her with an f-bomb; she parried by calling him a bitch—she said he’s more moderate off stream.

Even his abrasiveness could be taken as proof of his commitment to his beliefs. Unlike the “woke bros” who become socially progressive to stoke their personal reputations, Bonnell does not care about how he’s received. He gets paid to talk, but he seems to genuinely believe that we would all be better off if people who are suffering were treated well. He was making money prior to streaming about politics, and there’s no reason to believe that progressive politics are any more profitable than right-wing politics online.

Goransson, who is from Sweden, first met Bonnell in person on a trip to New Zealand after she’d seen a video of him recording a podcast and reached out to him on Instagram. She gets messages from Bonnell’s audience like “You’re dating a piece-of-shit pedophile, lib cuck.” He chalks it up to jealousy: “They hate anybody that takes you away from them.” Whenever she walks by or joins the stream, they throw down throngs of angry Pepe emotes, Twitch’s customizable version of emojis. (Bonnell explains that they’ve reclaimed the cartoon frog, usually seen as an alt-right mascot, laughing at me for being a normie and not already knowing that.)

Bonnell has spawned a sprawling and passionate community. While the hub of the universe is a Twitch chat that always runs alongside his stream, there’s also a large Discord server that he spends less time in, as well as a private chat for subscribers—his most committed fans.

When streaming, he monitors all of these chats and responds to comments in real time, which gives the community sway over what he talks about and does. “They hate it when I play League of Legends,” he told me while streaming, as the chat flared back in a cascade of agreement. While the relationship is asymmetrical, it isn’t fawning: Like close friends or siblings, viewers give him a ton of shit. When Bonnell went to the bathroom, they tried to get me to delete the game because, according to one user, when he plays it “he gets quiet, angry, and toxic.”

“Yeah, that’s true,” he said with a dark, knowing grin when he returned. “You should have deleted it. You fucked up. But I have multiple installs on my computer just in case somebody sneaks in and deletes it.” While streamers can face real-world harassment like stalkers, swatters, and unwanted deliveries, I couldn’t tell if he was joking.

For their occasional vitriol, his fans also seem like kind, genuine people, not just trolls. When I logged in to the private chat, after a few attempts to make me the butt of one of the community’s in-jokes, they were eager to talk about Bonnell and their own lives. They even shared polls that they had conducted among themselves addressing my questions, warning that insincere responses may have somewhat distorted the results. One survey, taken by 4,051 purported fans, showed 59 percent disagreeing with “Destiny’s defense of saying the n-word in private,” and saying they themselves never used slurs.

While the community is tied to Bonnell, his fans sometimes gather to watch movies and TV premieres in a separate chat. When I ask why they’re there, they say it’s for each other. “The people in this chat have good memes. Also I have no friends,” one user explained.

Others mentioned loneliness, but many say they’re attracted by how left-wing the chat is compared to other gamer spaces. Many are students, but a lot self-identify as neet, meaning “not in education, employment, or training,” which has become a reductive stereotype for gamers who post from the comfort of their parents’ basement, with few social or economic opportunities. In a 2018 poll that Bonnell conducted, not only were the overwhelming majority of his users under 30, but most were under 23. Ninety percent said they were cis men, and 88 said they were nonreligious.

His viewers appreciate his debating prowess against experienced conservatives, and positively relish his messy, beat-down debates with weaker opponents, like the one about police brutality that flew off the rails. “Most of the fan-favourite debates are due to them being entertaining chaotic shitshows, rather than being engaging or thought provoking,” one user told me.

At around 9 p.m. on Sunday, after watching Bonnell stream almost continuously since noon, I decided to call it a night. He was wearing the same black hoodie with a hole in the left sleeve that he had worn each day I’d seen him. He got up and hugged me.

“See you later, man,” he said before going back to his computer and playing a game I didn’t recognize, laughing and muttering back and forth with the chat. As I walked out, the apartment was lit by monitors, but otherwise dark.