Activists rallied outside the Supreme Court in Washington D.C. as it heard oral arguments in a case involving Republican-backed abortion restrictions in the state of Louisiana. Jeff Malet/ZUMA

While we didn’t plan for this interview to happen during a pandemic—yes, I know, I feel like I could say that with just about anything right now—it was actually good timing. Mary Ziegler, a Florida State University law professor, has spent her career studying the legal history of abortion, and just as her latest book, Abortion and the Law in America: Roe v. Wade to the Present, was coming out in late February, the country was beginning its descent into lockdown mode, and over the next few weeks, the fight over abortion access would again pop to the foreground, with several states brazenly trying to use the virus to impose outright bans of the procedure.

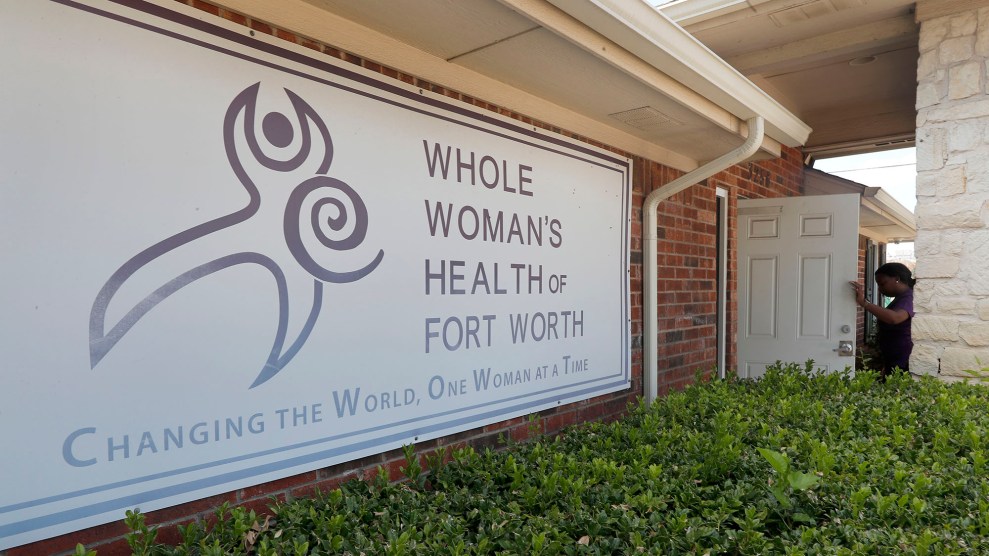

At the same time, abortion advocates were bracing themselves for a monumental moment: a ruling in June Medical Services v. Russo, the first abortion case to reach the Supreme Court since the makeup of the bench changed to a conservative majority, one with the dangerous power to kickstart the path toward reversing abortion rights across the United States. As my former colleague Jessica Washington wrote in March, at issue is “a stayed 2014 Louisiana law requiring doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic where they provide abortions…[one] almost identical to a Texas measure that the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional in the 2016 case Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstadt as placing an ‘undue burden’ on women seeking abortions by forcing many clinics to shut down without a justifiable health purpose.”

In her new book, which effectively functions as a legal roadmap for how we got to our current moment, Ziegler carefully examines the forces that have shaped the way we talk about abortion law, from the original Roe ruling to the rise of the religious right to Donald Trump’s election to the White House. It’s a comprehensive analysis of all factors—legal and sociological—that have fueled the anti-abortion movement’s determination to end legal abortion. Here, we discuss what can be learned from the recent battles over abortion during the pandemic, whether abortion rights could be saved under Democratic leadership, and how much John Roberts’ legacy is in play. This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Over the past couple months, we’ve seen an unceasing back and forth in the federal courts over state bans on abortion during the pandemic. As states are beginning to open back up, the fight has died down for now, but is there anything in history for us to compare that battle to?

I mean, no, but I think in terms of the abortion politics, there’s very much a through-line between the COVID-19 abortion bans and what was happening before the pandemic—in terms of not just the ambitions of these states, which obviously have remained the same, but also the strategies that they’re using to get there. Even though we’ve been talking about functionally banning abortion in these states, there’s virtually no discussion of abortion rights, or even about fetal rights. Instead, almost all of the emphasis is put on these claims about what the situation on the ground is like in Oklahoma or Arkansas or Texas, and whether abortions use up personal protective equipment. This is something I study in the book: how we got to a place where both sides seem to be fighting about these questions about the reality on the ground, and the facts about abortion and abortion restrictions, rather than the rights that are at stake. And the answer to that is that a lot of anti-abortion activists and legislators think that this strategy is a much more effective way to chip away at Roe and ultimately eliminate it, rather than something more direct, like, for example, focusing on a right to life.

I was really struck by the part in the book about how initially the Hyde Amendment—which bans the use of federal funds for abortion care—was largely overlooked by abortion rights groups because they were counting on the courts to strike it down. And then, of course, the courts didn’t. Is there anything like this that you see in this moment, that you think isn’t getting enough attention, or the magnitude of which isn’t being quite understood?

Well, the effect of ordinary abortion restrictions, which of course are still on the books in almost all states and in many of the states that did impose bans. Whenever there’s a ban—whether it’s a proposed constitutional amendment or something like Alabama did last year or the COVID-19 bans—that’s what grabs our attention, and that’s what we focus on. We lose sight of the fact that there are already restrictions like the Hyde Amendment that are in effect that no one is challenging or that have already been unsuccessfully challenged, which are really affecting what access to abortion looks like and many of which may ultimately have more of an impact on what happens to Roe. So I think it’s easy to get kind of distracted by bans because they are so much more dramatic, but the history would tell you that that can be misleading and can lead you to ignore things that are going to matter just as much.

Do you think there’s any chance of the Hyde Amendment being overturned?

Not in court. We have, everybody assumes, a fairly conservative Supreme Court, and even if a Democrat were to get elected in 2020, it’s hard to see the court moving in a progressive direction on abortion. Maybe they’ll hold the ground, but nothing more than that. I think there’s some chance that you could see a legislative repeal of the Hyde Amendment, and that’s still not a sure thing. There have been plenty of moments in history when Democrats have controlled the White House and both houses of Congress and have still chosen not to repeal the Hyde Amendment.

But I think what’s changed is that there’s more of a consensus in the Democratic Party on the need for the Hyde Amendment to go. That was pretty visible this year during the 2020 Democratic primary when even Joe Biden, who had been part of a bipartisan consensus in favor of the Hyde Amendment, eventually gave up on backing it. I think that said as much about what the Democratic Party believes about abortion and the Hyde Amendment as it does about Biden. I just think that’s kind of a consensus position, and also I think there will probably be at least some effort to do that if Democrats take Congress in 2020. I don’t know if it’ll be successful. The Hyde Amendment has become almost a permanent feature of our landscape when it comes to abortion, so it’s not going to go easily. But I think you’ll see a push in that direction.

What are some things you’re going to be looking out for in the upcoming Supreme Court case?

There are obviously the major questions that the court is considering that anyone is going to want to look out for—what they say about who can challenge laws in the first place, what they say about the fate of Whole Woman’s Health, obviously what they say about precedent, which they’ve been talking a lot about lately (albeit not in the context of abortion). We should also be attuned to the way they talk about the issues. The court’s dealing with this argument that abortion hurts women—I traced that argument in the book and where it came from and the why—but sometimes the way the court talks about abortion can tell you a lot about where they’re going as much as what they actually formally decide. So it’ll be interesting to see if the justices—and especially some of the swing justices, like Roberts—seem to take seriously the argument that abortion hurts women.

For Roberts, I think the case is probably a lot about what you mean when you talk about precedent—when you respect precedent, what constitutes a precedent. That draws on some of the historical questions in the book because Brett Kavanaugh, for example, recently has written that one of the things you should think about when deciding whether to overturn a precedent is whether it’s had bad societal effects. To know the answer, he’d have to look at the history of what happened after Roe or Casey or Whole Woman’s Health. I think the question of what we even mean by “precedent” is probably going to be one of the questions at the heart of the case.

Do you agree with some of the analysis out there that Roberts’ decision may come down to him considering his legacy?

Yeah, I do. And I think there’s also a question of optics with Roberts. Not necessarily that Roberts would never overturn Roe because of fears about his legacy, but he might be more reluctant to overturn Roe in a way that seems overtly political or brazen. I think a big part of that is how he deals with precedent, especially when you’re talking about a case like Roe. As Kavanaugh himself said during his testimony before Congress, that’s a pretty old precedent that’s had lots of hard looks from the Supreme Court. So undoing a precedent like that is something that he wouldn’t take lightly if he is concerned about his reputation.

Do you think it’s more likely that instead of an opinion that will overturn Roe, this case could be the beginning of a series of cases that will slowly chip away at Roe?

I do. If you want to be really cynical, if you view the court as a political actor, there’s much less in the way of political fallout that would come from a decision like that. On one end of the spectrum, if the court overturned Roe tomorrow and did it in a really open way, that would probably produce a lot of popular blowback. By contrast, if the court did it gradually, that might produce less backlash, and if what the court is doing is not even clear at all, if you need to call somebody like me to even know what it means, that’s likely to produce less backlash too. Lots of people will be functionally disenfranchised because they won’t understand what’s going on. So it’s more likely, given some of these reputational concerns, that the court would want to either proceed gradually or just stay away from really clear decisions altogether.

Do you feel we get a little too caught up in the Roe ruling and in using it as a shorthand for abortion rights?

Yeah, and when we talk about Roe, we mean a lot of different things. We almost never mean the 1973 Supreme Court decision. We could mean abortion rights, equality for women, reproductive justice. There are times when that’s fine, when Roe v. Wade is a rallying symbol, and that’s not a problem. There are times when it’s really confusing, because when we’re talking about, for example, Roe v. Wade being overturned, Roe v. Wade sort of already has been overturned. So you’d be talking about abortion rights being eliminated, and it’s much more helpful then to think about stuff that’s happened after Roe, like Casey or Whole Woman’s Health. Roe has this really amazing, unique symbolic power and that’s both very compelling but can also be very confusing for people who are trying to make sense of what’s going on.

Can you elaborate on what you mean by “Roe has already been overturned”?

In 1992, we were in a moment very much like this one where there was a Supreme Court that had more than enough people who were conservative on it to overturn Roe. And the court declined to do so formally, but it did revise in pretty fundamental ways what abortion law looked like. Roe had adopted the trimester framework, under which states could do almost nothing to restrict abortion until after fetal viability, which would be the time that a child could survive outside the womb. Only at that point could the state advance its interest in fetal life. And Casey undid that and said instead that the state had an interest in protecting fetal life throughout pregnancy, and that restrictions would only be unconstitutional if they created a substantial obstacle for women seeking abortion. No one really knew for certain what the undue burden tests meant then, and they still aren’t sure now, but one thing that was surely clear was that it was less protective of abortion rights than whatever came before.

The reason talking about overturning Roe is misleading is because we already have a framework that’s less protective than Roe, and because a lot of the action is about what the undue burden test means, both in terms of the effects of abortion on women and communities and also the effect of abortion restrictions on women. Roe takes up so much space that we sometimes lose sight of the fact that we’re no longer asking the same questions that the court did then.