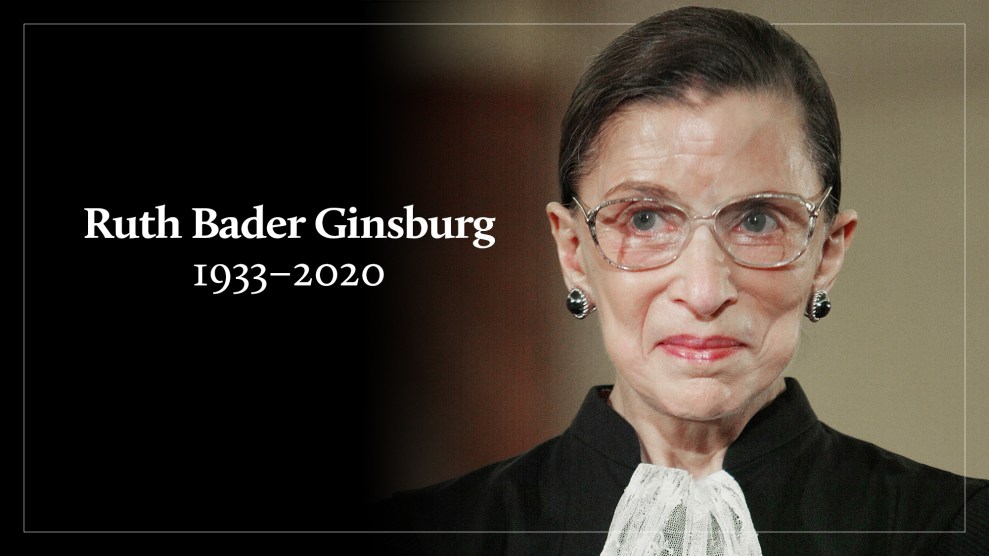

Jeffrey Markowitz/Getty

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wanted more for women.

While everyone has been screaming about Roe v. Wade since her death Friday night, it’s worth remembering that the beloved justice was famously critical of the landmark ruling, which was based on the right to privacy rather than a woman’s right to bodily autonomy. She was also frustrated that subsequent judicial decisions put the right to an abortion in the hands of lawmakers and (mostly male) physicians, rather than the women who needed care. Ginsburg, simply put, cut through the bullshit from the get-go; she would never be satisfied with anything less than complete, perfect equity.

We shouldn’t be, either.

In 2020, it’s not exactly novel to say that the Roe decision is terrible. Even though it has been canonized in the zeitgeist as shorthand for “legal right to abortion,” it’s pretty widely accepted that the decision is poorly constructed on weak doctrine, especially considering the historical heft of the thing. But Ginsburg was critical of the ruling before it was cool.

In fact, she was so reproachful of the court’s reasoning in Roe that a lecture she gave at New York University in 1992 alarmed the president of the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), prompting her to call on senators, who were then considering Ginsburg’s nomination to the Supreme Court, to discern “whether Judge Ginsburg will protect a woman’s fundamental right to privacy, including the right to choose, under a strict scrutiny standard.” It’s almost comical now—the idea that Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Notorious RBG herself, our patron saint of feminism, could possibly be anything less than pro-choice. But at the time, her words were radical. Even her allies weren’t sure what to make of them. “Measured motions seem to me right, in the main, for constitutional as well as common law adjudication,” she argued. “Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable. The most prominent example in recent decades is Roe v. Wade.”

A couple beats later, she elaborated: “The idea of the woman in control of her destiny and her place in society was less prominent in the Roe decision itself, which coupled with the rights of the pregnant woman the free exercise of her physician’s medical judgment. The Roe decision might have been less of a storm center had it both homed in more precisely on the women’s equality dimension of the issue…”

She was never one to identify a problem without also bringing up a potential solution, or, in this case, a model for a one. In her 1993 Senate confirmation hearing, when she was asked about abortion and this lecture about Roe, she cited a case she argued in the 1970s for the ACLU, Capt. Susan Struck v. Secretary of Defense. In the case, a female Air Force captain became pregnant while serving, and she was given the option to either terminate the pregnancy or lose her job. In her defense, Ginsburg argued that the Air Force’s decision violated the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment—after all, men were not forced to choose between procreation and military service. The other two key elements of Ginsburg’s argument were that the Air Force was violating Struck’s religious freedom—she was Catholic—and her liberty as established in the due process clause, because a woman’s choice is paramount to her freedom. (Ultimately, Struck’s discharge was waived, and the case did not make it up to the Supreme Court.) But as Ginsburg noted in ’93 and many times after, the Struck case could have established a real right to reproductive choice; it wasn’t that she thought Roe’s grounding in privacy rights was bad, per se, it was that it would be stronger if it also included the equal protection defense. In those Senate hearings, she put her thoughts on abortion this way: “This is something central to a woman’s life, to her dignity. It’s a decision that she must make for herself. And when Government controls that decision for her, she’s being treated as less than a fully adult human responsible for her own choices.”

We like to boil Supreme Court justices down to their votes, using their positions to interpret their partisan leanings. But Ginsburg didn’t really think like that—her legal mind transcended party and expectation and milieu. For her, reproductive freedom was always about equality, the right women have to be respected in the world the same way that men are, which means the ability to make reproductive decisions on one’s own terms without fear of loss of income or job stability.

Ginsburg’s death now amplifies the threat to abortion access—and equality more fundamentally—to an ear-splitting degree. President Trump has already irrevocably reshaped the federal courts, stacking them with judges who value conservatism above the constitution and legal precedent. When the Supreme Court bench shifted further to the right after the retirement of Anthony Kennedy in 2018, there were two threads of hope left for abortion rights: precedent—particularly as laid out in Planned Parenthood v. Casey and Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt—and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Without Ginsburg, there is little standing in the way of a new Supreme Court case that questions the legality of abortion access. Her death swings open a locked door for anti-abortion legal advocates to rush through—and they will. And so people who hold abortion rights dear will need to fight like hell. But we also need to remember what Ginsburg, who could not just accept the “win” of Roe, taught us. She had more foresight and legal aptitude than to simply be complacent with Roe; she wanted something stronger, a ruling that could withstand future challenges and that centered women’s agency and health above all else. So as we fight for Roe and for our rights, remember Roe is not the gold standard of abortion law. Our work will not be done in just saving Roe. It feels impossible right now, but perhaps opportunity will rise amid the chaos. And anyway, a woman’s work is really never done—so let’s make sure RBG’s was not in vain.