Chinese immigrants arrested In New Jersey in November 1934.Gamma-Keystone/Getty

It doesn’t take longer than the table of contents to realize how much has stayed the same. “Separation of families.” “Invasion of personal rights.” “Illegal searches and seizures.” “Despotic powers of the administrative agency.” These section headings come from a 1931 US government report on the state of America’s deportation machine.

In 1929, President Herbert Hoover tasked former attorney general George Wickersham with producing a series of reports on law enforcement in the United States. Reuben Oppenheimer, a Baltimore lawyer, was put in charge of immigration. What he found was so appalling that it made the front page of the New York Times.

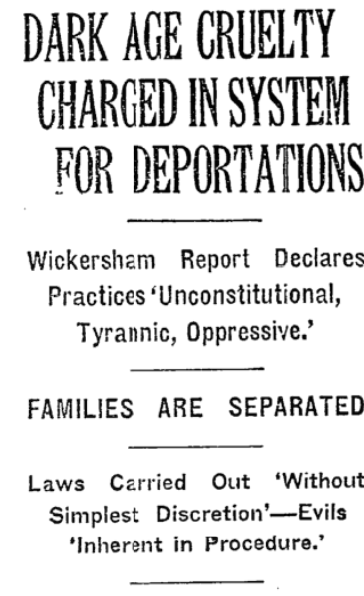

A 1931 New York Times headline summarizing Oppenheimer’s report.

New York Times

The denials that followed were familiar, too. William Doak, who oversaw deportations as secretary of labor, said the next day that the abuses happened before his tenure. A day later, John Trevor, the head of an anti-immigrant “patriotic” group, warned that he’d heard Oppenheimer was associated with the American Civil Liberties Union. Trevor added that the report’s recommendation to provide immigrants with attorneys would let them avoid deportation with the help of the “shysters who now disgrace the American bar.”

The Wickersham Commission’s largely forgotten report reveals that the immigration debate that’s torn the country apart under President Trump had the same contours a century ago: One side sees inhumanity in the detention and removal of people who came to the United States in search of a better life; the other sees the means necessary to keep out people they don’t want. It’s a reminder that long before Trump, America was violating immigrants’ rights as a matter of course.

If Trump leaves office in a few months, there will be intense pressure from liberals to quickly repeal his immigration policies. The Wickersham report makes the case for doing much more.

Oppenheimer was investigating immigration enforcement as a young Harvard-trained lawyer. Like Wickersham, who worked as a law partner at New York City’s oldest firm before becoming attorney general, he was an establishment reformer, not a radical. Both men believed some deportations were necessary, though the scale was different from today: At the time, the United States had been removing fewer than 10,000 people in an average year, versus the record of more than 400,000 set in 2012.

President Herbert Hoover with the Wickersham Commission. George Wickersham is second from the right, first row. Hoover is seated to his left.

Related Stories

America’s Immigration System Was Already Broken. Trump Made a Weapon Out of Its Shards.Asylum Is Dead. The Myth of American Decency Died With It.Trump Killed My American Dream: 8 Stories From the War on ImmigrantsWhy a Second Trump Term Would Be Even Worse for Immigrants

Still, Oppenheimer concluded that those deportations led to an “almost inconceivable amount of suffering and hardship, of separations of husbands from their wives and of fathers from their children, of exile from a country where the deportee has been a desirable citizen and has formed all his attachments.” He added, “These results occur for the most part not where the deportee has committed a crime but where he has been guilty of a technical violation of the immigrations laws.”

As an example, Oppenheimer mentioned a Mexican man with eight US-born children who wound up on the other side of the Rio Grande after a fishing trip. He was apprehended after returning and barred from the United States permanently after being deported. (A 10-year ban is more common today, although there’s usually no way to return in practice.)

Farther from the border, immigrant inspectors, the equivalent to today’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, made little effort to hide the fact that they valued deportations above due process. One inspector readily admitted to Oppenheimer that he was going to falsify an affidavit so he could deport a man he called a “bum.” It’s reminiscent of a scene in the recently released Netflix documentary series Immigration Nation, in which an ICE officer illegally picks a lock on camera. Then and now, lawbreaking was so routine that immigration agents didn’t think to hide it.

Once in custody, immigrants were detained in jails without the right to counsel. As today, most couldn’t afford attorneys, so they represented themselves in proceedings rigged against them. “In all probability a great many unrepresented persons have been deported whom lawyers could have saved,” Oppenheimer wrote.

An attorney and media attention didn’t guarantee protection, either. Oppenheimer told the story of Guido Serio, who fled Italy after being attacked by fascists. Serio told an immigrant inspector that he’d be killed in Benito Mussolini’s Italy. The government ordered him deported because he was a communist.

A federal judge recommended he be sent to the Soviet Union, which had offered to take him in. Instead, federal immigration officials deported him to Italy on the dubious grounds that it was best for his “welfare and protection.” In doing so, Oppenheimer wrote, they had decided to make “deportation a death penalty.” (Doak, the labor secretary, had defended the move, telling the Nation that there were some people who “think we ought to shoot him here before shipping him.”)

The abuses were systemic problems, not the fault of rogue agents. “It is inevitable,” Oppenheimer wrote, “that despotic power given should be despotically used.” He concluded that it was an “insufferable reflection upon our humanity” that so much power was provided with so “little opportunity for even administrative mercy.”

Doak held up publication of the report for months. (He reportedly had to be persuaded not to criticize Oppenheimer’s Jewish surname in his official response.) Once it was out, Doak claimed without evidence that the problems had already been fixed before making clear that his main priority was deporting more people. That effort was apparently going well: He had told the Nation that Ellis Island was “crowded to capacity” with people slated for deportation.

Trevor, the head of the American Coalition of Patriotic Societies, suggested that Oppenheimer was a communist sympathizer based on his ties to the ACLU. At a congressional hearing in 1939, a representative of the Immigration Restriction League dismissed the report as “merely” the findings of a “Baltimore immigration lawyer by the name of Reuben Oppenheimer” who was assisted by a New York immigration lawyer. (Like Oppenheimer, the New York lawyer, Bernard Flexner, also happened to be Jewish.)

In reality, communists hated the report. The Daily Worker, a communist newspaper, reported that left-wing groups deemed it largely “useless” to most immigrants. J. Louis Engdahl, a communist leader, declared that it avoided “the basic question, complete liquidation of the deportation evil” and failed to recognize the right to political asylum. From the left’s perspective, the “pussy-footing” report condemning the “modern Torquemadas of the Immigration Bureau” provided immigration enforcement with a path to legitimacy. For them, there was only one solution: “Smash the deportation drive.”

Like reformers after him, Oppenheimer believed “vigorous enforcement” of immigration laws could coexist with protection of individual rights. To achieve that, he suggested more discretion for officials enforcing immigration laws, better access to attorneys among immigrants, and the creation of the independent immigration court system that immigrant advocates are still fighting for today.

Despite everything he saw, Oppenheimer called for hiring more Border Patrol agents, as well as inspectors who would work with local authorities to find immigrants with criminal records. It’s essentially a 1930s version of the strategy Barack Obama pursued while setting deportation records before changing course under pressure from immigrant communities.

Biden has no plans to end deportations altogether if he’s elected, but the Wickersham report does give reason to think he can be pushed further than his predecessors. Oppenheimer wrote that public opposition often deterred abuse in other areas. But when it came to immigration, there just wasn’t that much public outcry. “[T]he defects and abuses of the present system must in part be laid at the door of public opinion,” he concluded.

After decades of activism and four years of Trump, there is no longer nearly as much indifference. Even today’s moderates can discern in our immigration system what yesterday’s radicals were describing. Here’s how the Daily Worker described the status quo in 1931: “Workers are seized and torn away from their families, held incommunicado for weeks and months, grilled and terrorized by immigration inquisitors, frequently transported over long distances to deportation points under conditions unfit for humans, then thrown into filthy pens crowded to bursting, and finally deported to countries where militant workers face certain death and imprisonment.”

Substitute “asylum seekers” for “militant workers” and you’ve got the system we have today, as characterized even by staid mainstream news outlets. Tinkering—a few more lawyers here, better-trained immigration officers there—wasn’t enough in 1931 and isn’t enough now.