Adam J. Dewey/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

The gallery in the Idaho House was restricted to limited seating on the first day of a special session in late August. Lawmakers wanted space to socially distance as they considered issues related to the pandemic and the November election.

But maskless protesters shoved their way past Idaho State Police troopers and security guards, broke through a glass door and demanded entry. They were confronted by House Speaker Scott Bedke, a Republican. He decided to let them in and fill the gallery.

“You guys are going to police yourselves up there, and you’re going to act like good citizens,” he told the invaders, according to a YouTube video of the incident.

“I just thought that, on balance, it would be better to let them go in and defuse it … rather than risk anyone getting hurt or risk tearing up anything else,” Bedke said of the protesters in an interview last week. He said he talked to cooler heads in the crowd “who saw that it was a situation that had gotten out of control, and I think on some level they were very apologetic.”

That late-summer showdown inside the Statehouse in Boise on Aug. 24 showed supporters of President Donald Trump how they could storm into a seat of government to intimidate lawmakers with few if any repercussions. The state police would say later that they could not have arrested people without escalating the potential for violence and that they were investigating whether crimes were committed. No charges have been filed. The next day, anti-government activist Ammon Bundy and two others were arrested when they refused to leave an auditorium in the Statehouse and another man was arrested when he refused to leave a press area.

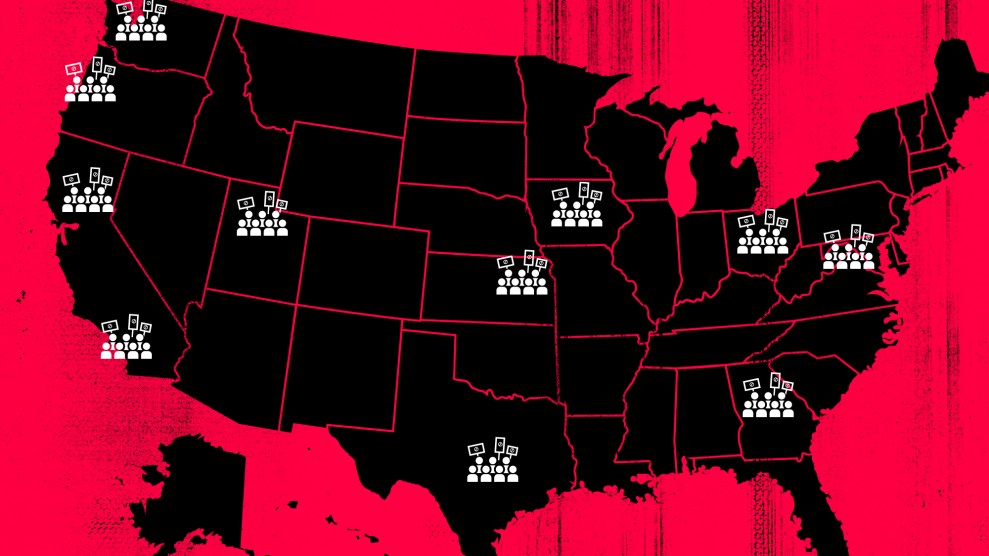

In a year in which state governments around the country have become flashpoints for conservative anger about the coronavirus lockdown and Trump’s electoral defeat, it was right-wing activists—some of them armed, nearly all of them white—who forced their way into state capitols in Idaho, Michigan and Oregon. Each instance was an opportunity for local and national law enforcement officials to school themselves in ways to prevent angry mobs from threatening the nation’s lawmakers.

But it was Trump supporters who did the learning. That it was possible—even easy—to breach the seats of government to intimidate lawmakers. That police would not meet them with the same level of force they deployed against Black Lives Matter protesters. That they could find sympathizers on the inside who might help them.

And they learned that criminal charges, as well as efforts to make the buildings more secure, were unlikely to follow their incursions. In the three cases, police made only a handful of arrests.

The failure to stop state capitol invasions is especially chilling after the attack on the US Capitol, which left five dead, including a police officer, as lawmakers met to certify the election of President-elect Joe Biden.

Experts and elected officials said the lack of action by lawmakers and police created an environment that encouraged political violence. The FBI has warned of armed protests occurring in all 50 state capitols in the run-up to the inauguration on Wednesday. Authorities in both Washington and state capitols have dramatically strengthened security.

“Eventually, you get to the point of entitlement where you can get away with anything and there will never be any accountability,” the Idaho House minority leader, Ilana Rubel, a Democrat, said. “I don’t know that (Bedke) was wrong under the circumstances, but it adds up to creating a sense of entitlement.”

Bedke said he saw no correlation between the events in Boise and Washington. But domestic terror experts said in interviews that the statehouse invasions likely created a sense of impunity among right-wing activists. The feeling grew throughout the year as Trump praised gun-carrying activists at state capitols as “very good people” and emboldened the insurrectionists in Washington.

Amy Cooter, a Vanderbilt University sociologist and expert in the militia movement, said the US Capitol attack may have been less likely to occur if the violence in state capitols had been met with harsher punishment.

What’s more, she said that authorities who failed to take action against protesters earlier may find it difficult to do so now.

While many Trump supporters already see their First Amendment rights as being under attack, they may see efforts to block them from state capitols as an attack on their Second Amendment rights, she said, further legitimizing their need to stand up to what they perceive as tyranny.

When officials acquiesce to demands, “it typically makes these folks feel like those are ‘constitutional’ officials who support their general aims, which can then embolden them against officials they believe to be the opposite, that is, officials they believe to be betraying their oaths to the people,” Cooter said.

If extremist groups “believe they have been given allowances in the past and are not moving forward, this can further reinforce that notion of officials who are derelict in their duty, officials who should be removed and, depending on what group we’re talking about, possibly officials who should be confronted with force.”

Days after Trump tweeted “LIBERATE MICHIGAN,” protesters taking part in an “American Patriot Rally” outside the Michigan Capitol in Lansing on April 30 swarmed into the building demanding an end to the stay-at-home order put in place by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

The group, which numbered in the hundreds, included several heavily armed men. Few wore face coverings or observed social distancing. A line of state police troopers and other Capitol employees held the mob back from entering the House floor.

“We had hundreds of individuals storm our Capitol building,” state Rep. Sarah Anthony said in an interview. “No, lives were not lost, blood was not shed, property was not damaged, but I think they saw how easy it was to get into our building and they could get away with that type of behavior and there would be little to no consequences.”

Some armed invaders entered the Senate gallery. While none of the protesters faced charges, two of the men seen in a photo posted by state Sen. Dayna Polehanki looking down on lawmakers would be among the 14 people charged months later in a plot to kidnap Whitmer and bomb the state Capitol.

“It made national and international news, what happened in our Capitol,” Polehanki said in an interview. “People saw that, and it’s no coincidence that the storming of the US Capitol on Jan. 6 had the same feel.”

Polehanki, a Democrat from Livonia, asked the state’s Republican-majority Senate to support a resolution banning firearms in the Capitol. But it wasn’t until Jan. 11, five days after the US Capitol insurrection, that theMichigan Capitol Commission voted to ban the open carry of guns inside the building. Open carry is still allowed outside the building, and people who have concealed pistol licenses can still carry concealed weapons inside.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel tweeted that visitors should stay away from the state Capitol because it is “not safe.” Some legislators have begun wearing bulletproof vests.

The memories of the April 30 invasion still haunt Anthony, a Democrat from Lansing. “The level of anxiety and fear that was intended to be imposed upon those of us in the building will probably stay with me for the rest of my life.”

As the legislators convened to vote, Anthony said she sat next to state Rep. Brenda Carter, D-Pontiac, another Black woman who was afraid of being targeted by the invaders. “We look like Democrats, so I think when you have individuals who are not only carrying large firearms but also carrying Confederate flags and nooses and swastikas, those have specific messages targeted to Black and brown communities.”

Days later, she arrived at the Capitol building with an escort from five armed constituents.

An angry mob didn’t need to break down a door to enter the Oregon Statehouse in Salem to disrupt a one-day special session on Dec. 21. A surveillance video released two days after the US Capitol insurrection revealed that Republican state Rep. Mike Nearman, of Independence, opened a locked side door to let in some violent protesters.

The building, normally open to the public, had been closed since mid-March because of health concerns. But several dozen demonstrators gathered outside in a “flash mob” organized by the far-right group Patriot Prayer, which has been tied to protests in Portland. Dozens of rioters streamed into the building and attacked police officers.

One of the Patriot Prayer supporters who carried an AR-15 rifle into the Statehouse was charged with pepper-spraying six police officers. Five other protesters were also taken into custody.

Nearman would later issue a statement defending his action by noting the state Constitution mandates open public legislative proceedings. He was removed from legislative committees and billed for damages caused by the rioters. House Speaker Tina Kotek, D-Portland, called on him to resign. Nearman and Kotek did not respond to requests for comment.

Nearman’s conduct had parallels to concerns among some in Congress that perpetrators of the US Capitol attack had help from police or even lawmakers. Rep. Mikie Sherrill, D-N.J., said she witnessed lawmakers giving “reconnaissance” tours the day before the Capitol attack.

“They couldn’t have done what they are doing without some notion of impunity around it,” said Lawrence Rosenthal, chair and lead researcher of the Center for Right-Wing Studies at the University of California-Berkeley. He said militants cling to a fantasy that if a civil war were to break out, what some extremists call a boogaloo, police and the military would join their side. Those notions may have been corroborated at the state capitols, Rosenthal said. “The type of wink-wink quality that these guys experienced.”

At least three men involved in the effort to invade the Oregon Statehouse appeared to have joined the insurrection at the U.S Capitol, according to Oregon Public Broadcasting.

One of them, Tim Davis, 59, of Springfield, Oregon, told ProPublica he “couldn’t comment” about whether the riot in Salem inspired him to travel to the nation’s capital. He insisted he did not join those who entered the US Capitol building or break any laws.

“The president asked people to come, and I felt it was my constitutional duty to go,” he said.

Alex Mierjeski contributed research.