Gripas Yuri/Abaca via ZUMA Press

Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) has a pair of priorities as his party assumes control of the Senate for the first time in six years. One is sweeping legislation that tackles every facet of democracy reform, from gerrymandering to dark money and voter suppression. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) designated the bill as one of the first the new Democratic majority will likely take up.

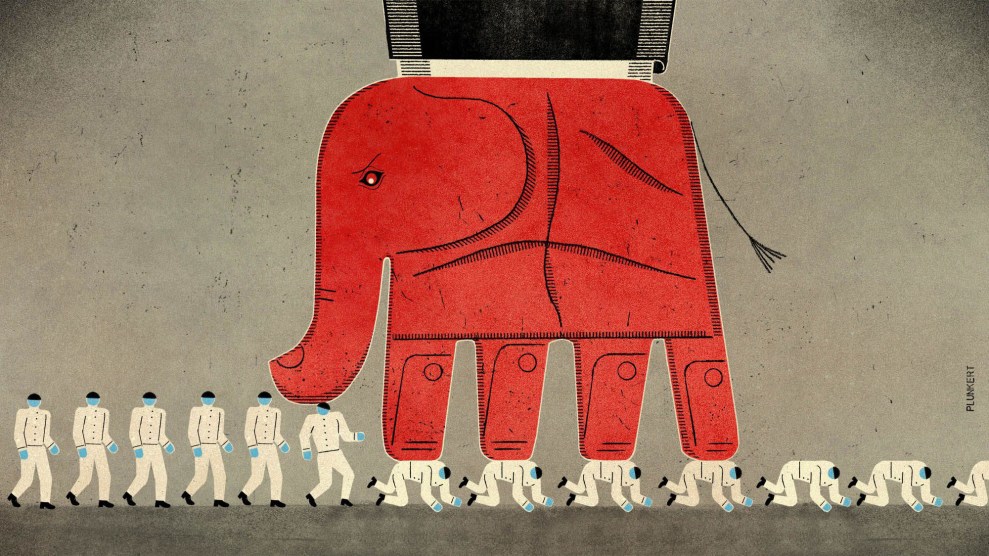

But standing in the way is the Senate filibuster, which de facto raises the number of votes required to pass legislation in the Senate to 60 instead of the simple majority of 51. The filibuster enables the minority party to block legislation, and it had primarily been used to halt the consideration of civil and voting rights bills. That changed a decade ago under Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), the Senate’s top Republican, when the filibuster was used for nearly all legislation and “absolutely paralyzed this place,” Merkley tells me. And Merkley warns that as Senate minority leader, McConnell will surely use it to stymie democracy reform.

“I do not think that it’s acceptable for us to say, ‘We’re going to let Mitch McConnell have a veto over Americans fundamental rights,’” he says. Hence another priority for Merkley: reforming the filibuster so his bill can be put on the Senate floor, amended and debated by his colleagues of both parties and put to a simple majority vote.

Ending the 60-vote filibuster has been Merkley’s hobby horse for some time. In 2012, he proposed a less radical step with a call to restore the “talking filibuster,” which would force debate to block legislation. For years, his push had been a lonely one. More than a dozen of his Senate Democratic colleagues joined Republicans in signing a letter that promised to “preserve existing rules, practices, and traditions” in the Senate. Since last summer, he has been meeting privately with colleagues to discuss possible filibuster reforms, and nearly all of those remaining Democratic signatories have sided with him. So, too, has former President Barack Obama, who called the practice a “Jim Crow relic” in a eulogy for civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) last summer. Like President Joe Biden, Obama began his presidency with unified Democratic control but witnessed the minority party railroad his agenda at every possible opportunity when he lost that filibuster-proof majority in 2010.

There’s a lot Democrats want to achieve in this window of opportunity. At the top of the list is Biden’s $1.9 coronavirus relief package and a jobs and infrastructure package to follow. But the party is already at war with itself over how to govern with such narrow majorities, particularly in the Senate, where Vice President Kamala Harris gives the Democrats a one-vote edge. Biden, who spent more than three decades in the Senate brokering bipartisan deals, has signaled a preference for the parties to work together to come to a consensus. He told the New York Times last fall that he opposes overturning the filibuster, and White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters last week that his position “hasn’t changed.” Others have staked their hopes on the budget reconciliation process, which allows for certain tax- and spending-related legislation to pass with a simple majority of 51 votes.

But the Democrats’ democracy reform bill doesn’t have a single Republican co-sponsor, and it likely doesn’t qualify for the reconciliation process. And so Democrats and activists who support Merkley’s push see only two available options: “We see this as the choice between keeping the filibuster and fixing our democracy,” Leah Greenberg, a co-founder of the progressive grassroots group Indivisible, tells me. “We need the Democratic caucus to view it that way, as well.”

On matters of democracy reform, protecting the filibuster allows Republicans to hold onto their grasp of political power by blocking likely Democratic voters. Passing Merkley’s bill and the House’s voting rights bill, another top Democratic priority, would safeguard rights for the historically disenfranchised—most notably, Black Americans. In statehouses where Republicans retain control, lawmakers are already busy crafting tightened voting restrictions to dampen the chance Democratic candidates could succeed in future elections. Merkley says his Republican colleagues have told him McConnell has forbidden GOP senators from backing his bill.

That’s why Merkley sees ending the modern-day filibuster and his party’s proposed democracy reforms as two sides of the same coin. “You have this incredibly racist history of voter suppression, systemic discrimination,” he says, “and you have the filibuster deeply associated with systemic racism, as well.” Passing those bills would rectify “this tilt of power toward predominantly white conservatives in our system,” adds Adam Jentleson, who worked as an aide to former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and recently published a book calling for filibuster reform. “The sequencing is important because you can’t do any of the other things unless you do filibuster reform.”

To Jentleson, the fate of the filibuster is a matter of political survival for Democrats, too. From his perch in Reid’s office, he had a front-row seat to the ways McConnell thwarted Obama’s agenda, then turned around and blamed Democrats for inaction. The tactic cost Democrats seats in both chambers of Congress over those election cycles. Jentleson says there’s tremendous political risk in “getting strung along” by Republican lawmakers only to end up with “small-ball deals” that fail to meet the country’s dire moment. “Bipartisanship is a worthy goal,” Jentleson tells me, “but delivering results to save this country has to be the ultimate goal.”

So how do Merkley and his fellow filibuster detractors prevail with their colleagues who still resist filibuster reform? The path, Merkley says, is probably to get caught trying to get 60 votes on top agenda items, then watch Republicans block them. If Biden’s coronavirus package fails, Merkley predicts, it will “move people’s hearts” to not allow McConnell a veto “that may cost tens or thousands or 100,000 people in this country their lives.” The same goes for his party’s democracy reform bill. “If it comes down to an issue as fundamental as the right to vote and Republicans block it,” Merkley says, “I think that would have a significant impact as well.”

That impact would have to be significant. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.), who told the Hill last summer he was intrigued by Merkley’s pitch on filibuster reform, remains opposed to ending the practice. So too, does Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), whose spokesperson told the Washington Post this week that the senator is not only “against eliminating the filibuster,” but also “not open to changing her mind” on the matter. Optimists on the side of filibuster reform hope the moderate Democrats might be open to less extreme reforms than total abolition. One picking up steam is something Sen. Bernie Sanders floated during his presidential campaign: Expanding what’s allowed under budget reconciliation by overriding guidance from the Senate parliamentarian.

In the progressive imagination, abolishing the filibuster crosses a threshold toward more ambitious structural reforms. For the party’s left flank, the proposed democracy and voting rights bills are the baseline. Granting statehood for Washington, DC, abolishing the electoral college, expanding the numbers of seats on the Supreme Court, and enacting a ranked-choice voting system would be necessary steps to rebalance the scales against the tyranny of minority rule. Legislation has been introduced to address each impediment, but not all Democrats are on board with big moves. Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) recently told the Atlantic that the votes for DC or Puerto Rico statehood aren’t there, even if the filibuster is abolished (even though the House passed a bill to grant DC statehood last year). For now, Democrats’ debate on the future of the filibuster delays facing up to the divisions that remain within their caucus.