Nicole Bennett, a critical care nurse practitioner in Massachusetts, had always found humor and camaraderie in her Facebook group for nurses. She joined the group, called Nurses, in 2019, right after a Washington state senator had publicly suggested that nurses “probably play cards for a considerable amount of the day.” In the group, Bennett, whose name I’ve changed to protect her privacy, found nearly a million other nurses just as outraged as she was about the politician’s perception of their profession. The posts varied—from funny nurse memes to touching stories from busy shifts—but the comments were almost always supportive. When the pandemic hit, the group came together, cheering each other on as the worst of the first wave of cases came crashing over hospitals across the country. “It was a place of solidarity,” she recalls.

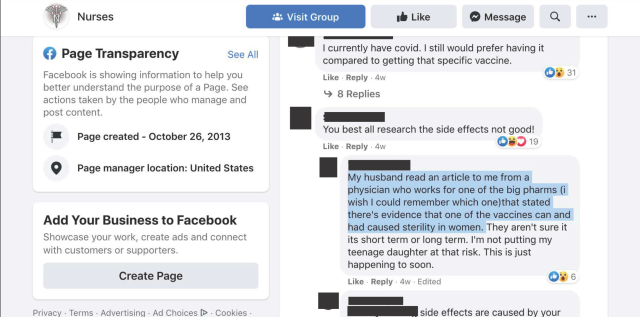

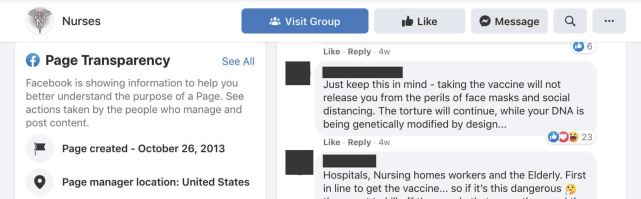

But this fall, Bennett noticed the tone slowly began to change. Members started posting about the US rollout of coronavirus vaccines, noting that health care workers would be first in line. While some in the group cheered this news, others railed against it. On December 11, a group administrator posted an article announcing the emergency use authorization of the Pfizer vaccine. “My husband read an article to me from a physician who works for one of the big pharms (I wish I could remember which one) that stated there’s evidence that one of the vaccines can and had caused sterility in women,” one commenter said.

Another commenter added: “Just keep this in mind—taking the vaccine will not release you from the perils of face masks and social distancing. The torture will continue, while your DNA is being genetically modified by design.”

Bennett knew that these claims weren’t supported by science—the mRNA vaccine can’t change DNA, and there is no evidence that it can cause infertility. So she politely pointed members to evidence of the vaccine’s safety. But over the coming weeks, vaccine myths took over the group—and they seemed to be swaying members’ decisions of whether or not to get vaccinated. A December 19 post by an administrator linked to an article about supposedly dangerous side effects. “After 50 years working full time as a nurse, I will retire rather than be forced to get it,” one commenter said. Bennett couldn’t take it anymore. “I’m embarrassed that other nurses think and feel this because they represent us,” she says. “I finally just left, because I can’t do this.”

Bennett was surprised to see fellow nurses falling for unscientific rumors about the vaccine. The nurses she knew kept up with medical journals and were proud of their expertise. Yet the vaccine skepticism in her Facebook group is emblematic of a larger trend. In a December survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 29 percent of health care workers expressed doubt about the COVID-19 vaccines. In some hospital systems, the number is much higher. The LA Times reported that half of health care workers in California’s Riverside County refused the vaccine. Some reasons for their hesitance are understandable: Many worry that the vaccine was hastily developed; others resent overbearing hospital administrators forcing them to get a shot on top of increasingly impossible pandemic workloads. For some health care workers of color, wariness is rooted in their history of trauma at the hands of the medical establishment.

Thus far, there’s been no unified effort on the part of the government to address these valid concerns. As a result, in the absence of clear and easily accessible information, many health care workers turn to social media, where rumors can take hold and spread. Indeed, I found vaccine misinformation in every nurse social media group I visited. On the Facebook group of Nurseup.com, a community for nurses with more than 4,000 members, administrator Andrew Lopez regularly posts memes touting the supposed dangers of the COVID-19 vaccines. Members of the Facebook group Funny Nurses, with more than 1.7 million followers, have shared memes likening vaccination programs to Nazi concentration camps.

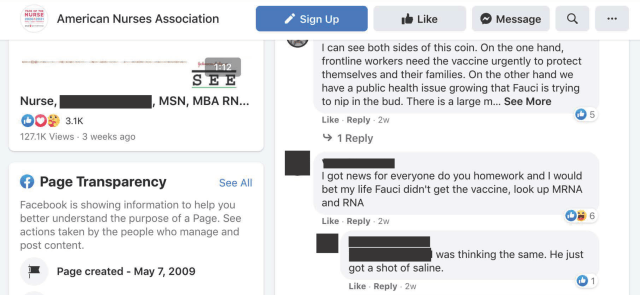

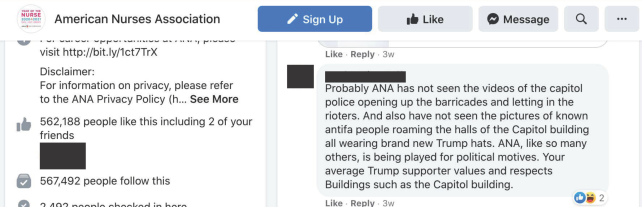

The misinformation even proliferates on the Facebook page of the American Nurses Association, the nationwide professional group for nurses that offers certification and continuing education credits. ANA members circulated a theory that the government faked the TV vaccination of Dr. Anthony Fauci and he actually received a saline solution rather than vaccine. Why? Because he too was aware of the dangers contained in that syringe.

The conspiracy thinking in the American Nurses Association Facebook group surged beyond just the vaccine: In response to a January 6 post condemning the riot at the Capitol, a member claimed in the comments that antifa had been responsible for the mob that stormed the Capitol. (After this story was initially published, American Nurses Association spokesperson Keziah Proctor noted in an email that the group has published social media guidelines for nurses, and that it provides immunization education for nurses.)

This rapid online spread of vaccine misinformation among nurses alarms Rupali Limaye, a Johns Hopkins public health researcher who studies vaccine hesitancy. “If you’re the one providing vaccines, and you yourself are hesitant, then what’s your role in recommending the vaccine?” she asks. “There is an assumption that you’ll just go along with it, but people can’t put their personal opinions aside.”

The effort to educate nurses about COVID-19 vaccines has been piecemeal at best. National Nurses United, the country’s largest nurses’ union, has offered online trainings and webinars, and many individual health care systems and hospitals have made similar efforts with their staff. Some nurses are taking it upon themselves to set the record straight, posting selfies of their vaccination appointments on social media, says Jean Ross, a registered nurse and leader of National Nurses United. Still, she says, the lack of a coherent message from the federal government and the chaotic rollout of vaccines has created perfect conditions for misinformation to flourish. “When it comes to people who are leery, that can be placed right at the foot of [the Trump] administration,” she says. “When agencies we think we can rely on—like the CDC, OSHA, our president—when we can’t rely on them because of lies and downgrading of guidelines, then there’s a whole lot of mistrust and distrust to overcome.”

Melody Butler, a nurse who works in infection prevention outside New York City, has taken it upon herself to set the record straight. Butler runs a nonprofit called Nurses Who Vaccinate, which aims to arm health care workers with accurate information about immunizations. Her interest in vaccine advocacy is personal and dates back to 2009, when New York State was considering the idea of requiring health care workers to be vaccinated against the H1N1 strain of influenza. Butler was wary. She was pregnant, and she had read online that the vaccine caused miscarriages, and that it had been secretly tested on an island where it had caused severe illness and death. “Some of the websites, they looked really professional,” she recalls. Finally, a fellow nurse convinced Butler that these were myths, taking the time to show her the abundant evidence that the vaccine was not only safe and effective, but that contracting the H1N1 virus would be more dangerous to her fetus than getting the vaccine. “This was a conversation that took place over a couple of shifts,” she says. “I eventually was convinced and educated about how important it was for me to get the vaccine.”

A few weeks later, a nurse friend of Butler’s who was pregnant with twins contracted H1N1 and lost one of her fetuses. Shaken, Butler founded Nurses Who Vaccinate with the goal of educating her colleagues about the benefits of vaccines. Today, the group has more than a thousand nurse members. That may not seem like a lot compared to other online nurses’ groups, but the members are tireless in their outreach. Recent efforts include a partnership with the New York Health Department, through which Butler gave a series of in-person presentations to New York nurses about the importance of vaccination and how to stop the spread of misinformation.

Butler and the other members of Nurses Who Vaccinate are also spending a lot of time sifting through online communities to identify and root out COVID-19 vaccine misinformation. She’s heartened by the amount of vaccine enthusiasm she sees, and also points to the abundance of vaccine selfies. “But unfortunately, the anti-vaccine nurses are always the loudest,” she says, noting that some nurses who posted about getting the vaccine “are dealing with a lot of harassment and threats.” For pregnant nurses, the backlash is particularly vicious: “They’re attacked, accused of harming their unborn child.”

One reason for nurses’ hesitance, says Ross, could have to do with the perception that they might be forced by hospital administrators to get vaccinated against their will. “This is how employers treat us,” she says, “they try to force the flu vaccine every year, they say you won’t be able to work if you don’t get one.” Yet the idea of requiring nurses to get vaccinated against COVID-19 could backfire, warns Johns Hopkins’ Limaye. Even before the pandemic, she says, at many hospitals, relations between administrators and nurses were already tense. For nurses who often feel as if they are at the bottom of a power and pay structure while doing most of the hard work, it doesn’t take much to feel exploited. The last pandemic year has only exacerbated those tensions, as nurses logged long shifts, often in dangerous conditions. “It’s a new vaccine, and in the context of a pandemic,” says Limaye, “you’re asking people to put their lives on the line, and then adding this requirement?” Instead, she recommends that hospital administrators first take time to listen to nurses’ fears and concerns and take them seriously. If nurses feel supported by their superiors rather than exploited, they might be more likely to trust information about vaccines that comes from hospital administrators.

Irene Treadwell, a New York City nurse who runs a support group for African-American nurses called Black Nurses Consortium, echoed Limaye’s concerns. She added that many administrators don’t understand that some nurses of color are wary of vaccines because of real trauma their friends and families have experienced in hospitals. Indeed, from the horrendous experimentation on Black people during the Tuskegee Study to earlier this year when Black physician Susan Moore died of COVID-19 after being sent home from the hospital, “There is a chronic pandemic of biases in the health care system,” says Treadwell.

National Nurses United’s Ross says she is irked by headlines about nurses refusing the COVID-19 vaccine, since rarely do the reports explain the underlying reasons for their hesitancy. Indeed, accounts about health care workers’ resistance don’t reflect her own experience. She says most nurses she knows can’t wait to be immunized—especially since many hospitals still don’t provide them with adequate PPE. “I was quite surprised to hear the news about hesitancy among health care workers, because our nurses have been impatiently waiting for the vaccine,” she says.

Bennett, too, says that the misinformation she saw in her Facebook group doesn’t reflect the opinion of nurses in her circle, where not a single nurse has refused the vaccine. But she knows that online rumors are insidious, and she worries about the lasting damage they could do to her profession. “Nursing is the most trusted profession—people believe us, they listen to us, they trust our judgment,” she says. “It only takes one bad nurse to sour your opinion of nurses.”

The challenge of winning back nurses’ trust is a big one. It will require the federal government to step in with strong messaging about the safety of vaccines, combined with more support for the health care workers who risk their lives every day. Hospitals will also have to invest in relationships with nurses and other staff to make space for conversations like the one Nurses Who Vaccinate’s Butler had with her colleague many years ago. Nurses “are overworked and exhausted,” says Limaye. “Before we ask them to administer and recommend vaccines to others, first we need to actually listen.”

This story has been updated.