Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP/Getty

While campaigning in Iowa in early 2016, Donald Trump proclaimed, “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters, okay. It’s, like, incredible.” Trump essentially did that in the last days of his presidency. He promoted a January 6 rally for what he called a “wild” day in Washington. After an incendiary speech from Trump at that event, the crowd that he had assembled—which was full of white supremacists, neo-Nazis, QAnoners, Christian insurrectionists, and other extremists—turned into a murderous mob that followed Trump’s instruction to march on the Capitol to “fight like hell” and “stop the steal.” There his marauders attacked the citadel of American democracy, killing one police officer and seriously harming scores of others, with some trying to hunt down the vice president and House speaker, possibly to assassinate them. For hours, while the violent mayhem ensued, Trump did nothing to stop it or protect the lawmakers and cops targeted by his brownshirts.

On Saturday February 13, a month later, Republican senators proved Trump’s “shoot somebody” boast had been dead-on accurate: in his second impeachment trial they voted to let the man who had incited a lethal and seditious riot off the hook.

There is good news for adherents of the rule of law. In a historic move, a bipartisan majority of the Senate—48 Democrats, two Independents, and seven Republicans—did vote to convict a president who had been impeached by the House (also with a bipartisan majority). This has never happened before. Neither of the two presidents previously impeached—Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton—ended their impeachment trials with a bipartisan majority condemnation. And that did not occur with Trump’s first impeachment. The impressive presentation of the House managers did persuade members of Trump’s own party that he was guilty of inciting an insurrection. So now it is on Trump’s permanent record. More than half of the members of Congress, including Democrats and Republicans, have rendered a severe verdict: the 45th president was responsible for a deadly assault on the Capitol.

Trump will escape punishment for this act of betrayal, the greatest political crime in American history. But he will not escape judgment. This partial reckoning—Trump declared a villain—will stand forever. Moreover, future generations will watch the harrowing video of the assault on the Capitol the way we today view the footage of “Bloody Sunday” in Selma and reach the appropriate conclusions about what transpired. They will recoil. The Trump-inspired raid on Congress will not look better with the passage of the time.

Nor will the votes of those 43 Republican senators who refused to hold Trump accountable and who refused to signal that his politics of hate, deception, and violence are not acceptable within a constitutional democracy. Each GOPer who voted to acquit was saying that Trump’s post-election actions—his crusade to subvert the results, his effort to inflame his supporters with disinformation, his attempt to defy the popular will and hold on to power, his move to further incite the rioters once they were rampaging on Capitol Hill, his dereliction of duty on the day of the attack—were permissible under the constitutional order of the United States.

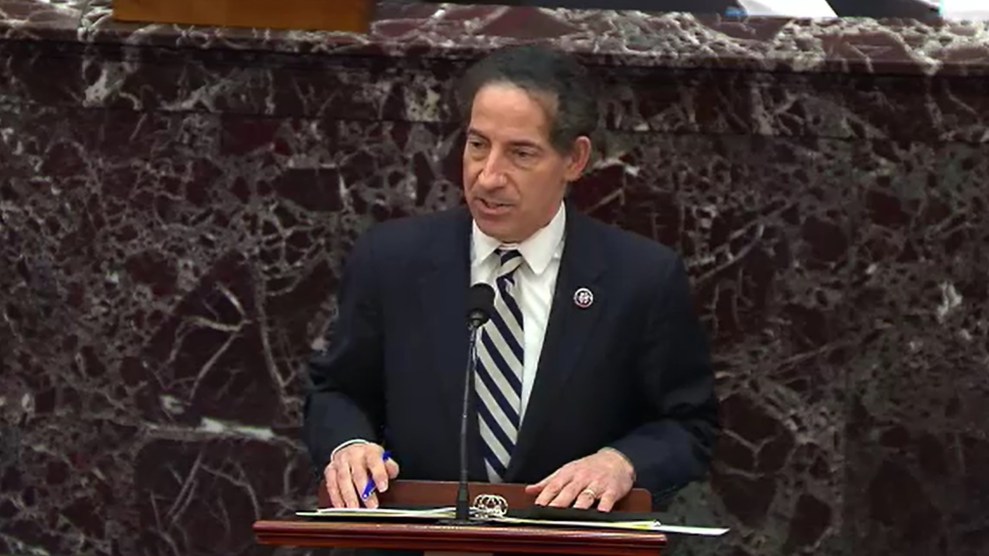

Perhaps worse, days before voting to acquit Trump, most of the Republicans, including leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), backed a failed resolution declaring the trial was not constitutional because Trump was out of office—meaning that they believed Trump could not be held responsible by Congress for his conduct. For some Republicans, this was the purported reason for their final vote to acquit. Yet, as Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), the lead House impeachment manager, noted, this view creates a “January exception,” under which a president who loses an election can take extreme and underhanded steps to hang on to the White House without fretting about impeachment should he fail. The acquitting Republicans also endorsed the absurd legal argument put forward by Trump’s B-team lawyers that his speech at the rally (and elsewhere) was protected under the First Amendment and, consequently, could not be the predicate for an impeachment. Under this bizarre analysis, if a president advocated implementing a dictatorship and establishing concentration camps, he or she could not be impeached. (Trump’s lawyers during their presentation tossed out an assortment of Trumpian lies and conspiracy theories: there was no evidence that Russia hacked the 2016 election; Antifa was involved in triggering the violence at the Capitol.)

But for the Republicans, nothing mattered. Not the evidence. Not the arguments. Not even what was arguably the most incriminating part of the manager’s presentation: when Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Texas) showed that during the attack, Trump, rather than trying to stop his savage supporters, put out a tweet that further inflamed the brutal seditionists running amok in the Capitol against Mike Pence, who was then in hiding. (“Hang Mike Pence!” the insurrectionists were shouting. And on the Capitol grounds, a gallows had been constructed.) A power-hungry president endeavoring to thwart a constitutional exercise—the certification of the electoral votes—had endangered his own vice president. And the final day of the trial focused on a statement from Republican Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler recounting a conversation between House GOP leader Kevin McCarthy and Trump on January 6 in which McCarthy beseeched Trump to end the attack and Trump replied that the insurrectionists were more on his side than McCarthy. This was more evidence Trump had abandoned his duty to protect the US government.

For most Republicans, all this Trump misconduct did not warrant convicting Trump or banning him from seeking the presidency in the future. (Though Trump had already been “removed by the voters”—as his impeachment lawyer Bruce Castor put it—an impeachment conviction was necessary for Congress to subsequently prohibit Trump from running again for the presidency.) And Republicans were declaring that Congress should not and could not punish Trump to prevent a repeat of January 6. “This cannot be the future of America,” Raskin contended during the trial. The Republicans did not concur.

As they allowed Trump to get away with murder, these Republicans were chaining themselves and their party to a zombie ex-president. They were on trial as much as Trump. Could they finally break with him and Trumpism? No. Weeks ago, after Trump was impeached for a second time, pundits were discussing the possibility of a civil war within the GOP over whether to distance the party from Trump, but that moment passed quickly. One sign: House Republicans voted to support Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, the assassination-encouraging, Trump-loving Georgia Republican. And this acquittal further demonstrates that the Republican civil war has been settled. Actually, it was barely fought. As Greene said, “The party is his. It doesn’t belong to anybody else.” In short, the GOP is still a cult of personality. It’s not even party over principle; it’s one man over all else.

The second impeachment trial of Trump placed the GOP in the dock. “This trial in the final analysis is not about Donald Trump,” Raskin intoned in his closing statement. “The country and the world know who Mr. Trump is. This trial is about who we are.” Especially the Republicans. Would they, he asked, condone Trump’s actions that led to the attack? Moments later, they did. Their vote for acquittal was not only a vote for Trump; it was a vote for political violence, a vote to undermine constitutional governance. It revealed their calculation that the King of Mar-a-Lago holds the dark heart of the GOP and maintains a grip on its most ardent voters. Even though his January 6 misdeeds may render Trump unelectable, should he pursue a restoration in 2024, these Republicans cannot elude his gravitational pull. They cannot defy Trumpism. So they will march—or crawl—into the historical record as handmaids to an authoritarian thug who sought to sabotage the political system of the United States. Their vote of acquittal is proof of their own guilt.

Trump is gone. But the death and destruction of January 6 will not be erased. The second impeachment of Trump and the subsequent trial produced a stark account of Trump’s dangerous assault on American democracy. The House impeachment managers failed to achieve the near-impossible goal of winning over recalcitrant Republicans. But their harsh and damning indictment of Trump—endorsed by a bipartisan majority—will permanently define Trump’s legacy. And this acquittal will be a heavy burden for GOP. With this vote, the Republicans will forever be part of Trump’s mob.