This story was published in partnership with the Delacorte Review.

Steven Tendo kept everything he owned under his bunk bed mattress. His pillow was a lump of letters, transcripts, and postcards—all that remained from a past he had fled and paper-thin promises of what life could become. Tucked among them were photographs of Montana’s sprawling flatlands and mountains set against a blue sky. Montana reminded him of Uganda and home. A plane ticket to a new beginning in Helena, Montana, awaited him.

But he had to manage to be released from Charlie 2, a dreary dormitory at Port Isabel Detention Center in the Texas town of Los Fresnos, about 15 miles north of the border with Mexico. Tendo had been incarcerated many times in his home country, but the six months in custody of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement had been his longest. He had been at Port Isabel since shortly after arriving in the United States in December 2018, seeking political asylum. The facility stood near the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge, a sanctuary for migratory birds. It had once been part of a military base, but now, surrounded by a 10-foot-tall chain-link fence with barbed wire, it looked unmistakably like a prison.

“You live in grief,” Tendo told me, “as long as you’re here.”

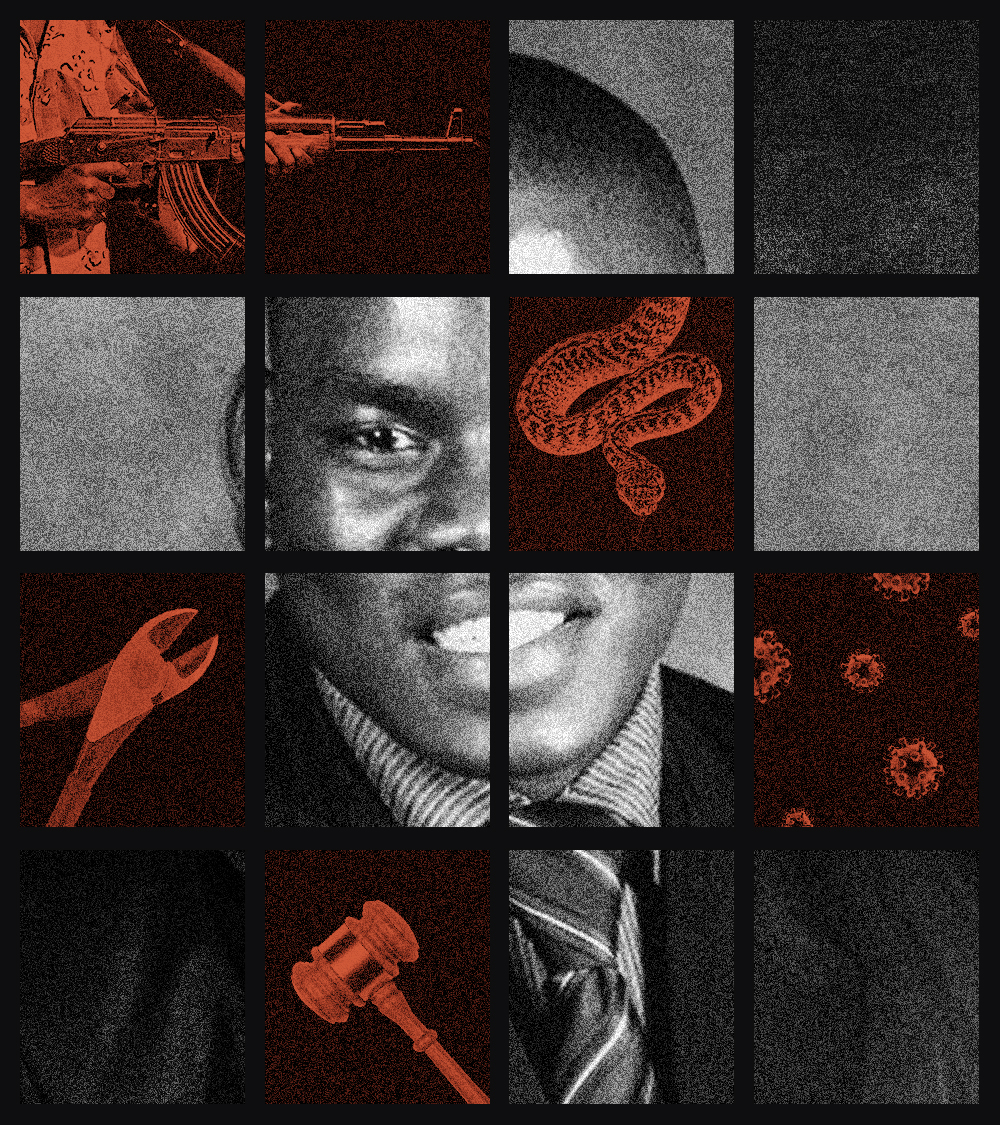

He hoped that time would soon be over. And so, on the June morning in 2019 of the fourth and final day of his asylum hearings, he prayed. At 34, Tendo was about 5 feet 8 inches, with a shaved head, piercing eyes, and a shy smile. He walked into the frigid courtroom wearing navy blue pants and a matching shirt with the detention center’s initials PIDC stenciled on the back. The room could accommodate only three wooden benches lined up on each side. The walls were so thin it was possible to hear the proceedings in the room next door.

The immigration judge was familiar with his case—how Tendo believed that his work as a human rights activist had made him a target of the Ugandan government, which had abducted and tortured him repeatedly. To tell his story Tendo had put to use all the English he had ever learned. He drew upon old memories blurred from the passage of time and others so fresh and haunting they stayed with him when he returned to his dormitory. Tendo had also shown the judge evidence he believed was indisputable proof of his story: he held up his left hand where there was a gap above the joints where the middle and ring fingers once had been.

Still, his lawyer, Thelma Garcia, who had been practicing immigration law for more than 40 years, knew that bruises, scars, and missing body parts alone might not be enough to convince a judge. She also knew asylum seekers could not be sure that their stories of persecution and victimization—so complex and unthinkable that they defied logic and common understanding of human behavior—would be believed. In fact, Garcia knew that given the way the system was set up, they likely wouldn’t be. For her clients to prevail and win asylum in the United States, everything came down not to a jury, or a hearing panel, but to a single person, a judge. Port Isabel had some of the toughest.

“If they don’t find you credible,” she said, “whatever you say, it’s not going to count toward anything.”

Steven Tendo’s case and fate had fallen to Judge Frank T. Pimentel, a former assistant United States attorney appointed to the immigration bench in 2017 by then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions. According to a review of decisions rendered by immigration judges between 2015 and 2020 by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University, Pimentel had denied almost 89 percent of 288 asylum cases. He worried Tendo. Pimentel, he said, “spoke softly but wasn’t a soft man.”

The odds were against Tendo. He had survived torture and traveled across continents to save his life. But now having reached his ultimate destination, he faced his biggest trial: to be believed by a system seemingly designed to doubt almost everyone—and punish them in the process.

Tendo was born into a world of plenty. His mother was a princess and his father a local chief in Buganda, once the most influential of Uganda’s traditional kingdoms. They had five children and an eight-bedroom house on the top of a hill. More than 2,000 cattle grazed the vast compound. The family had servants and hosted parties and luncheons most weekends with performances by local musicians. On Sundays, Tendo used to watch from a balcony as people came from afar and offered gifts such as bananas, rice, and meat to his parents.

This charmed life ended when Tendo was 13. Both parents, still in their early 40s, died of AIDS, which by the 1990s had infected almost 30 percent of the population in parts of the country. Relatives descended on the family home, making financial claims. In time and with nothing to call their own, the children were left to provide for themselves. Tendo took on odd jobs as a gardener and a cashier, and at a publishing company assembling newspaper pages. During the day, he studied.

Tendo’s parents were devout Christians—his name means “praise” in their native Luganda language—and he grew even closer to his faith in the years after their death. He eventually was ordained a minister and founded his own nonprofit organization, ELOI Ministries. He traveled to preach in neighboring countries like Rwanda, Kenya, and Tanzania. At home, Tendo became an advocate for the incarcerated, advising them on their rights to legal representation and also counseled young people about the dangers of drugs and crime.

In 2010, when he was 25 years old, Tendo entered into an agreement with the government’s Ministry of Gender, Labor, and Social Development to provide health and education services to children, women, and the elderly. In February 2011, Uganda held its presidential elections. Yoweri Museveni, a former guerrilla leader who first rose to power in 1986, was declared the winner in a process tarnished by accusations of corruption and fraud. Protests followed but they were swiftly crushed by Museveni’s National Resistance Movement. The fraught political moment led Tendo to shift some of the organization’s efforts towards civil education and access to justice programs. ELOI Ministries started encouraging young people, who make up almost 80 percent of the country’s population, to register to vote.

Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni attends the state funeral of Kenya’s former President Daniel Arap Moi in Nairobi, Kenya.

John Muchucha/AP

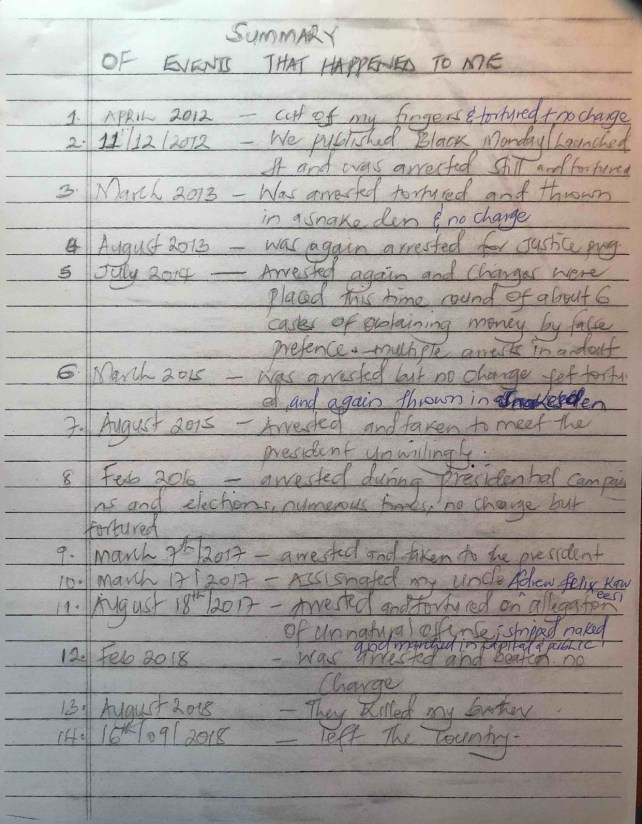

The government, he would later tell Judge Pimentel, regarded these initiatives as a dangerous opposition to its rule. Verbal threats followed. Then, one morning in April 2012, Tendo was on his way to work when he stopped at a gas station in the capital city, Kampala. Two men got out of a Toyota Mark II, and one opened his coat just enough to reveal a weapon. They forced Tendo into their car and ordered the gas station’s manager to keep Tendo’s vehicle. They covered Tendo’s head with a sack so he would not know where they were taking him.

The men drove for hours until finally at dusk they reached one of the city’s many hills. When his face covering was removed, Tendo could see what looked like military barracks. He had been taken to what was called a “safe house,” one of an unknown number of detention facilities where the Ugandan security forces were accused of torturing political prisoners, according to Human Rights Watch.

Inside, Tendo said, two armed officers slapped him on both cheeks. “Who’s sponsoring your organization? Which political figure is behind your activities?” they kept asking, as the blows intensified. Tendo’s nose bled and he cried for mercy, unable to give them the answer they wanted. One of the officers then approached him, and Tendo saw he held a wire cutter. Slowly, the man started cutting Tendo’s fingers piece by piece. The pain was so bad that he could no longer think. When it was over, he was transported to a military clinic where a doctor stitched up the wounds and staunched the blood.

On his first day of hearings on May 10, 2019, Tendo told Judge Pimentel, “I lost words,” as he held up his left hand to show him where the fingers were missing. “I lost words to tell them.”

He had been in their custody for three weeks when an officer arrived with new orders: Tendo was to receive what was called the “VIP” treatment, a euphemism for torture that left no visible marks. He was moved to an underground room with a single source of light. The space was empty except for what Tendo said was a python. The snake had a rope tied around it. It was too far from Tendo to bite him, but every time one of the jailers pulled the rope, the python whipped its tail against Tendo. The torture, he told the judge, lasted for four or maybe six hours—at some point he lost track of time.

He recognized the commanding officer as a leader of a government-sponsored, paramilitary anti-terrorism unit known as the Black Mamba. Its name comes from the deadly African snake.

Election officials count the ballots after polls closed in Kampala, Uganda, on January 14, 2021. Ugandans voted in a presidential election tainted by widespread violence that some feared could escalate as security forces tried to stop supporters of leading opposition challenger Bobi Wine from monitoring polling stations.

Jerome Delay/AP

Asylum cases are high-stakes tests in storytelling, in conveying a narrative judged to be plausible to an often-skeptical audience. Asylum seekers are asked to recount events most would hope to forget, and do so again and again, to asylum officers, lawyers, and finally, judges. This can go on for months, and all the while they are expected to tell their stories consistently, never overlooking details, or volunteering too much information, while still coming across as unassuming and inoffensive. Inconsistencies that can’t be accounted for can result in a denial and deportation.

Asylum seekers aren’t afforded the same protections as defendants in a criminal trial, who are considered innocent until proven guilty, nor is legal representation for them even guaranteed.

There is also no presumption of credibility. In May 2005, Congress passed the REAL ID Act, which raised the bar for asylum seekers across the board. In a stated effort to prevent terrorists from fraudulently slipping through the immigration system, the law encourages judges to attribute meaning to a person’s demeanor and candor. What that means in real life is that asylum seekers must attempt to anticipate not only every possible objection in matters of fact, but also objections to their presentation. The way someone sits or stands, how nervous they may appear, how responsive they are, or the pace of their speech can all be used against them. In effect, this has made it easier for immigration judges to deny cases based on credibility, with attorneys calling it nothing short of a tragedy for people with genuine claims.

When deciding the case of an asylum seeker from Togo, for instance, one immigration judge told the woman “passiveness and demureness” were not the order of the day. “If you’re really strong in your convictions you’ll express it in a strong manner,” the judge said. “If your answers are weak the Court may believe that you’re [sic] claim is also weak so conduct yourself accordingly.” Would a different judge have considered a “strong” assertion of her “convictions” excessive?

Researchers say immigration judges are especially susceptible to implicit bias when examining credibility issues. They might not be familiar with a specific country’s customs and circumstances and imperfect translation can lead to cultural misunderstandings. Appointed by the attorney general, many of them have spent their careers working as attorneys for the Department of Homeland Security or prosecutors with very little or no experience in immigration law.

Federal courts of appeals have long found a pattern of misconduct among immigration judges characterized by hostile, cruel, and abusive behavior. In fiscal year 2018, the department received complaints of misconduct against almost a quarter of the 321 immigration judges. The majority were related to due process and in-court conduct, and more than a third had to do with bias. Available data indicates that no judges were disciplined that year.

Immigration lawyers are increasingly turning to expert witnesses—legal historians or academics with relevant knowledge about the conditions of a certain country, or mental health specialists who can speak to behavior caused by trauma or gaps in testimony that might otherwise be misinterpreted in court. But not all asylum seekers can afford to hire an expert witness to fill contextual gaps. Judges inevitably bring to the bench their own assumptions and views of the world, typically Western ones.

“The only way to cut through all the complexity and inequalities of immigration courts is for expertise to be a requirement,” said legal historian and professor of African History at the University of Arizona Benjamin N. Lawrance. “Unless [judges] have the information in front of them, they’re making decisions based on their gut instincts or on cases they’ve heard before, which is contradictory to the whole promise of asylum that every case will be considered on its merits.”

Susan Dicklitch-Nelson, a professor of government at Franklin and Marshall College in Pennsylvania, has served as an expert witness in more than 100 political asylum cases from Cameroon and Uganda. She has witnessed firsthand how some asylum seekers’ stories can seem so implausible that they might be hard to believe. “It’s unfortunate when people who don’t have a credible claim say they do because it makes it harder for those who do have legitimate claims and are not trusted,” she said.

Inconsistencies, she added, signify our humanity. “If something is so candid and perfect it raises suspicion to me rather than if there are inconsistencies,” she says. “What most people don’t understand is that the entire future of your life is hanging on maybe a date or two. But how many of us remember the exact day we graduated from high school?”

After his initial day in court, Tendo went into the second hearing a month later feeling confident and optimistic. By then he had been in detention for six months. But on June 7, 2019 he encountered a skeptical Judge Pimentel. “When you went missing back in 2012, did your family report your absence to the police?” the judge asked him.

Tendo said his family had called an uncle in the Ugandan military who had heard rumors that he had been sent to one of the “safe houses.”

“No one,” the judge continued, “including your wife, including your relatives, went to the police and said, ‘our dear brother, our dear husband is missing, and we don’t know where he is?’”

“The trickiest thing, Your Honor,” Tendo said, “is that once the government is done behind something, they will do everything possible to make sure that they frustrate any efforts towards rescuing you from its hands.”

“So, wait a minute, Mr. Tendo,” said the judge. “Now, I’ve got to pause you there.”

“Yeah.”

“So, basically, what you’re telling me is, nobody goes to the police for anything in your country?”

“They called my—Your Honor, if it is not involved in government, or if it’s not the government trying to witch hunt you, but—”

“Well, how would your family know that?”

“They got rumors from the petrol station where I left the car, Your Honor—”

“Mr. Tendo, my point is, is that your family didn’t know you were abducted from a petrol station for quite some time. They couldn’t have known that.”

“No, they didn’t know, but my—”

“So, the excuse about the petrol station, you’ve got to try better, Mr. Tendo. You’ve got to do better than that.”

Tendo fell silent.

“Right? I mean, people go missing, people get frantic.”

“Your Honor,” Tendo replied, “even people are killed, and no reports are done at police, because even if you go to police and make a report, nothing is going to happen.”

“Well, that’s my question. So, you’re saying in your country, people just don’t go to the police when people go missing and disappear?”

“Unless if they—”

“I mean, if that’s your testimony, then—”

As Tendo told Pimentel, following his two-month detainment in 2012, he had been arrested and held more times than he could count and tortured in more ways than he could remember. On one occasion, he said, his interrogators threw cold water on him while threatening to cut his head off and feed it to alligators. On another, they burned him with candle wax and hot plastic. Tendo also told the judge that in May 2013, at another unidentified “safe house,” men from the Black Mamba tied a brick to his genitals and left him hanging for seven hours, until he started bleeding.

In 2014, Tendo attended a religious conference in the United States. When he returned to Uganda, he told the immigration judge that he was immediately taken into police custody and held for 12 days. After he was released a judge ordered him back to prison for 20 days, which turned into three months. What he did not know until later, he testified, was that his wife and the friend who had been the best man in his wedding were spying on him and sharing information with the government. Tendo also believed they were behind a scheme that led him to be charged with multiple counts of obtaining money by false pretenses, which were eventually dismissed, court documents show. (He and his wife are now separated.)

During one incarceration at the maximum-security Luzira Remand Prison in 2016, an examination documented in a letter from a medical superintendent at the hospital to which prisoners were referred revealed torture marks on Tendo’s head, chest, back, legs, buttocks, genitals, and hands.

By 2017, Tendo had gone into hiding, unable to stay in the same place for more than a week. He learned that his uncle, a senior police officer, had been shot to death outside his home. In August 2018, Tendo’s elder brother Yasin Kawuma was killed while driving an opposition leader to a political campaign gathering.

“I knew that I was the next target,” Tendo had told the judge in May 2019.

During the second and third hearings in June, Judge Pimentel questioned why Tendo’s school records indicated that he had been born in 1985 as opposed to 1984—his correct birth date as stated in passports and many other official documents—and pointed to discrepancies regarding travel dates and destinations in Tendo’s visa applications to attend religious conferences in the US from years before. He also noted that Tendo had failed to present evidence such as medical records attesting to his torture in 2012, nor was there corroboration that his deceased relatives were, indeed, his uncle and brother.

Garcia was concerned. She had taken note of the judge’s body language during the hearings and sensed that he was growing skeptical of Tendo. She had advised Tendo to “tone down,” fearing the judge might have found him arrogant or that he was “putting on airs.”

Looking back, Tendo remembers feeling as if his hearing had been turned into a criminal trial, where the judge was acting like a prosecutor and knew from the start he would deny the case. “Why would I doubt what I went through?” he told me. “I spoke with confidence because I knew there was nothing to lie about.”

In September 2018, Tendo left Uganda. He traveled through Ethiopia, Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Tendo said he was detained by Mexican authorities for more than a month in Reynosa, the Mexican city close to the border with McAllen, Texas. After being released, Tendo went to a shelter, where he met Jennifer Harbury, a well-known retired attorney who works with migrants in the Rio Grande Valley. Harbury advised Tendo and another Ugandan asylum seeker he had met in Mexico City to travel to Matamoros, where they would have an easier time crossing the international bridge to Brownsville on the US side.

He also connected with Valerie Hellerman, a former nurse and executive director of Hands on Global, a Montana-based nonprofit that leads medical teams to refugee camps in Greece and the US–Mexico border. Hellerman would later recall how Tendo and his fellow countryman huddled by themselves, conspicuous among the other migrants, who were mostly from Central America. “They seemed very desperate,” Hellerman told me. “I remember asking them what would happen if they went back home, and they said they’d be killed. That was clear in their minds.” Hellerman gave them money to get to Matamoros.

Cross-border commuters wait in line to enter Brownsville, Texas, via the Puerta Mexico international bridge.

Rebecca Blackwell/AP

Hellerman continued corresponding with Tendo and the other Ugandan asylum seeker after they crossed the border legally and were placed in a detention center in Texas. They complained to her about the conditions inside—how their bunk beds were right next to the one bathroom shared by dozens of people, and how they felt they were mistreated because they were Black. She offered to be their sponsor and house them once they were released. Tendo said she even bought him a plane ticket to Montana.

Both men would eventually have their cases heard by Judge Pimentel. The second man was granted asylum—the judge believed he had suffered retaliation for his political activity in Uganda—and upon his release was welcomed by Hellerman and her husband into their Montana home and church. He joined an international refugee resettlement program and found a job.

Tendo, meanwhile, remained in detention.

Closing arguments in Tendo’s asylum case took place on the afternoon of June 24, 2019. Tendo’s lawyer Thelma Garcia argued that her client had been credible and consistent, having given detailed and specific testimony. “The government has done everything in their power to break this man,” she concluded, emphasizing that he had suffered psychological and physical harm.

As part of Tendo’s asylum application, Garcia included more than a dozen reports and news stories documenting human rights violations and police brutality in Uganda. In 2018 and 2019, the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor reported that the Ugandan government was “reluctant to investigate, prosecute, or punish officials who committed human rights abuses.” Another study by Uganda’s Makerere University Law School’s Human Rights and Peace Centre found that the use of torture by security forces appeared to be “institutionalized and well planned.” The reports described treatment very much like what Tendo had testified he experienced.

Tendo and his lawyer also had submitted letters and affidavits from a neighbor and co-workers who witnessed his arrests over the years. One described how Tendo would cry for help when armed men picked him up and drove him away, leaving blood stains along the road. Sometimes it would be several weeks, sometimes months, before Tendo returned home, always with “horrible stories and scars on his body,” wrote the neighbor.

Protesters against police brutality in Uganda and the release of presidential candidate Bobi Wine stand in front of the UN Headquarters in New York City.

Luiz Rampelotto/EuropaNewswire/AP

One of those who wrote on Tendo’s behalf was a prison official—and distant cousin—who had seen how many times he’d been in and out of detention. In a signed declaration, the official said, “It is a foregone conclusion that in the event that Steven Tendo is deported back to Uganda, he will not survive the wrath of the security agents who wish to harm him.”

Still, the government’s attorney, Lily Dideban, focused on Tendo’s credibility, specifically asking the judge to evaluate his behavior.

“The respondent has not been candid nor forthcoming with the Court,” she said. “His claim is replete with implausible, inconsistent, and unbelievable claims.” Tendo’s demeanor, she continued, was rehearsed and his responses studied.

As he delivered his verdict it was clear that Judge Pimentel was sympathetic to the prosecution’s argument and had found it hard to believe in Tendo’s version of events.

“It is not more likely than not that the Ugandan government would acquiesce in or turn a blind eye toward any harm respondent might face,” he said. Steven Tendo, he ruled, was to be deported back to Uganda. When he heard the decision, shock rippled through Tendo’s body, a feeling he had only experienced once before: when his torturers severed his fingers. Back in the dorm he cried himself to sleep.

“The judge sentenced me to death that day,” he said. “If I knew what I know now I would have fought until my last breath.”

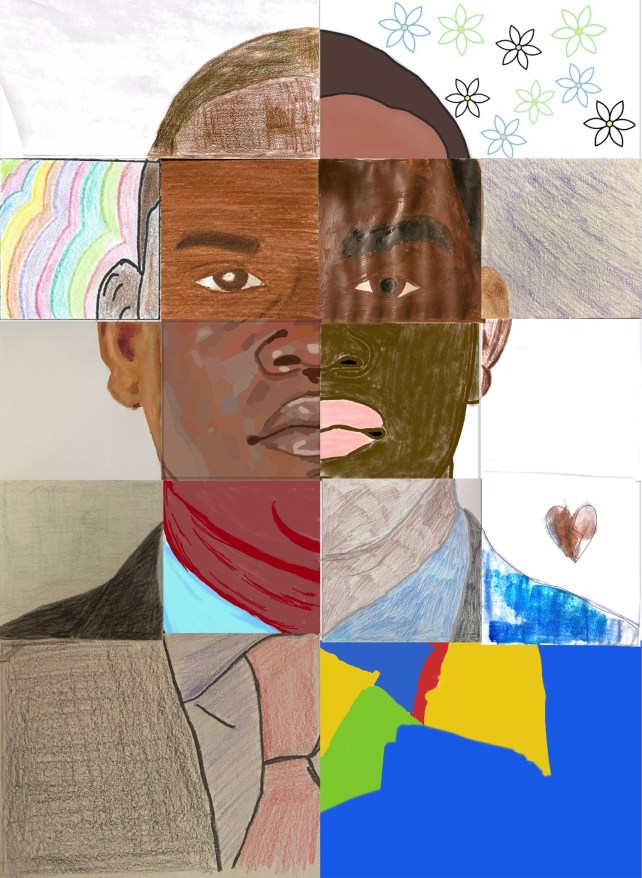

Students created a composite portrait of Steven Tendo.

Courtesy of the George School Amnesty International Club

Still, there remained options. Tendo appealed the decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals, an administrative body that has jurisdiction over the decisions of immigration judges. About three months later, on December 12, 2019, the Bbard denied Tendo’s appeal, citing inconsistencies raised by the judge and the argument of lack of evidence. The outlook of his case was looking grim, with ICE officials pushing to get his travel documents ready for deportation. But later that month, Jennifer Harbury, the retired attorney who would become Tendo’s sponsor, learned about new developments in Uganda.

In the early hours of Christmas Day 2019, seven heavily armed men broke into Tendo’s twin sister’s house, where she was alone with her three children. The men beat her with sticks on the head, back, hands, and legs, saying they had reason to believe that Tendo was back in Uganda and that she was hiding him. They threatened to kill her and dip her body in acid. There was no point in reporting anything to the police because they were untouchable, they told her.

“They asked me if my brother’s two fingers grew back because they wanted to cut off more,” she explained in an affidavit. Her right hand was so badly bruised that she couldn’t sign the declaration; instead, she had to use a thumbprint. In photos sent to Harbury via WhatsApp, she appeared lying in a hospital bed with bandages around the head, right arm, and knees. She later went into hiding.

Tendo’s appeals lawyer, Lisa Brodyaga, would try to show the new evidence, pushing to have the case reopened and either granted or returned to a different immigration judge. She also filed a stay of removal request to prevent Tendo from being deported in the meantime. The government attorney opposed it, questioning the authenticity and timing of the new evidence.

To supplement the testimony from Tendo’s sister, Harbury and Brodyaga received a declaration from the prison official familiar with Tendo’s torture. The official explained how once deportees arrive at the airport, they are treated as suspected terrorists and immediately handed over to the security forces.

“Running away from your tormentor is no work done,” the prison official told me from Uganda. “You’ll still end up in their hands.”

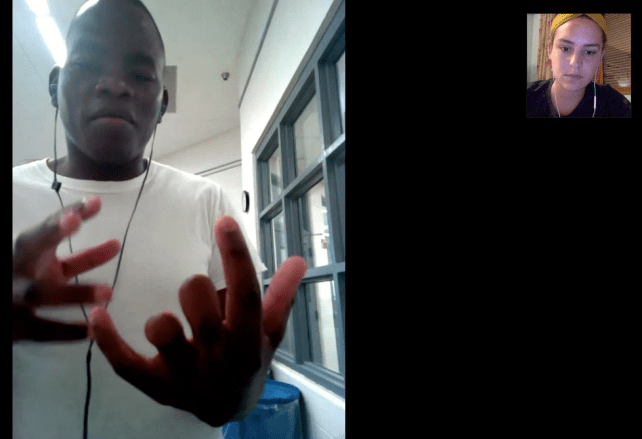

In late March 2020, a contract employee at Port Isabel Detention Center tested positive for the coronavirus, according to local news reports.

At this point, Tendo had been in detention for two years and suffered from high blood pressure, which subsequently led to the deterioration of his eyesight. He started feeling a sharp pain behind his right eye that spread to his entire face, and he was eventually diagnosed with cataracts. According to his medical records, he was at risk of going blind. During one of our many timed video calls, Tendo wore a white T-shirt and with his left hand, he scratched his right upper arm. He showed me bumps and rashes associated with diabetes and a skin infection. He was unable to maintain a balanced, low-sugar diet since meals often consisted of sandwiches, oatmeal, or rice. He often felt hungry and listless, sometimes dizzy with numbness in his limbs, but his multiple requests to change the diet or increase daily food portions went unheeded. He had lost almost 30 pounds.

After an outside doctor with the Migrant Clinicians Network evaluated his medical records, which amounted to 930 pages, he concluded that Tendo’s immune system had been compromised and any infection could kill him. In court filings opposing Tendo’s release, the government claimed to have prescribed him appropriate medication and diet since his arrival in detention. But Tendo’s lawyers said it took months for nurses to start checking his blood sugar levels twice a day, since he was not allowed to keep a finger-prick testing device. They also delayed providing snacks of fruits and milk, according to an August lawsuit seeking compensatory damages for ICE’s disregard for Tendo’s health.

In mid-April, Tendo sent Harbury a message that read: “I think they wanna kill me and deport a dead body. I am so frustrated, Jennifer, wondering if they have a personal grudge against me.” About a month later, he stopped eating for two days to protest his prolonged detention. In a letter shared with advocates and the press, Tendo wrote, “A dead body cannot be detained,” and closed with “In God I Trust.”

In late April, Cathy Potter, the attorney who filed the civil lawsuit on Tendo’s behalf, asked for a court order to immediately release him to “prevent potentially irreversible injury, up to and including death.” A district court judge denied it. By June, confirmed COVID-19 cases had spiked in the facility and more than 30 detainees reportedly tested positive. Around that time, Tendo started coughing, developed a fever, and had difficulty breathing. He could no longer smell his deodorant, another symptom of the coronavirus.

Over time, Tendo’s text messages to me grew increasingly desperate.

Tendo said his dorm had been placed under quarantine. A detainee who had tested positive was sleeping three beds away from him. “I don’t know what will happen to me if I get it again…I am just scared,” he wrote. “If this virus doesn’t kill me, nothing will.” Tendo told me he thought he was reinfected months later, but refused to get tested out of fear of being placed in segregation.

By the end of the month, Tendo was informed that he would be transferred the following day. He and his lawyers assumed that he was going to a different detention center in Laredo. He protested: His long-awaited cataract surgery was scheduled for the following week. The next morning, officers walked into the dorm and told him to pack his things. “You’re going,” they told him. According to Tendo’s account, he resisted and a group of officers grabbed him and knelt on his back to cuff his hands and legs. “They lifted me up like a coffin in the air,” Tendo told me in a video call.

But Tendo was not going to a different detention facility, he was going to the airport. Tendo saw another Ugandan waiting to be deported. “It’s a hoax and a lie,” the man told him. “They’re deporting you.”

Tendo’s destination was the Alexandria Staging Facility in Louisiana, often the last stop before a deportation flight. He was set to be deported on September 3, the same day his surgery had been scheduled. Meanwhile, Harbury and other volunteers were scrambling to locate Tendo and start a campaign to halt his deportation. In a letter to the Acting Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security Chad Wolf, 44 members of Congress wrote to express concern over Tendo’s imminent return to Uganda and asked the agency to release him on medical grounds while his federal appeal with the conservative Fifth Circuit was pending. Amnesty International and other human rights organizations also mobilized around his cause.

Tendo spent two nights in Alexandria before being moved to a detention center in Arizona, where he met at least ten other asylum seekers from Uganda, many of whom had also been victims of torture. At around midnight on September 7, Tendo learned that he wasn’t going to be deported after all. At least not yet. Still, he stayed and prayed with the others until 3 a.m. and watched as they cried and moved toward the plane.

“I will never forget that day,” Tendo said. “I was in so much fear.”

In November, back at Port Isabel, Tendo celebrated his 36th birthday, his second in detention. He received 21 letters and birthday cards—some from as close as Vermont, others from as far as Germany—which he was able to read after his successful cataract surgery in September. Tendo gathered 34 detainees in his dorm and bought soda from the commissary for each one of them. They made two cakes with crushed cookies they had mixed with milk and baked in a microwave, and beef tacos with chili and beans.

“My birthday was indeed a success,” he said. “Officers looked in amazement, one of them told me he had never seen anything like it in the last 18 years he has been working here. It’s a day I will never forget, maybe it represented a farewell for me as well from detention.”

Detainees at Port Isabel detention facility in Texas on December 17, 2008.

Jose Cabezas/AFP/Getty

That farewell finally came without a warning. On February 10, 2021, Tendo said ICE officers showed up at his dorm and told him he had 15 minutes to pack his belongings. For a brief moment, he still thought they might try to deport him, but as Tendo was heading out, he saw detainees in different dorms shouting and cheering him. After 26 months in detention, he was set free on parole.

“I looked back and thought about my friends who are still detained and I started hurting for them,” he said. “I used to feel so bad that people were leaving me there.”

His lawyers and advocates couldn’t explain the circumstances of his sudden release. It could have been the result of an order from a DHS official to create space for new arrivals. Perhaps it was a response by the new administration to negative publicity surrounding the deportations of migrants from Haiti and Cameroon.

After I heard he’d been released, I called his lawyer, Lisa Brodyaga, to ask what had happed. “Who knows, somebody might have woken up on the right side of the bed,” she said. “It gets pretty arbitrary.” She’s also “cautiously optimistic” about his asylum case moving forward. Last September, although the BIA rejected a motion to reopen the case, a judge dissented finding Tendo had overcome the negative credibility determination and the new evidence combined with the previous record in his case “likely independently establishes the respondent’s asylum claim.” That opinion could help sway the Fifth Circuit in Tendo’s favor, Brodyaga said.

Tendo was released just in time for the deadly winter storm that left millions of people without power and water. He stayed with another advocate for a few days before joining his sponsor, Harbury, in Weslaco, Texas. A future move to Montana is not out of the question.

On his first night as a relatively free man, Tendo still woke up at 5 a.m., imagining he had to get in line to be counted by the detention officers. When I called him a week later, he celebrated being able to talk on his own phone line, having space to run, and eating big pieces of chicken, fish, mango, and oranges for his meals. His sugar levels have already gone down. Tendo plans to get a work permit, go back to school to study law, and continue his advocacy work in the United States and Uganda, where the sitting president was once again reelected. Tendo still needs to wear an ankle monitor.

“It’s unbelievable that I’m free,” he said. “Sometimes I think to myself: Is this really happening? Yes, it’s happening.”