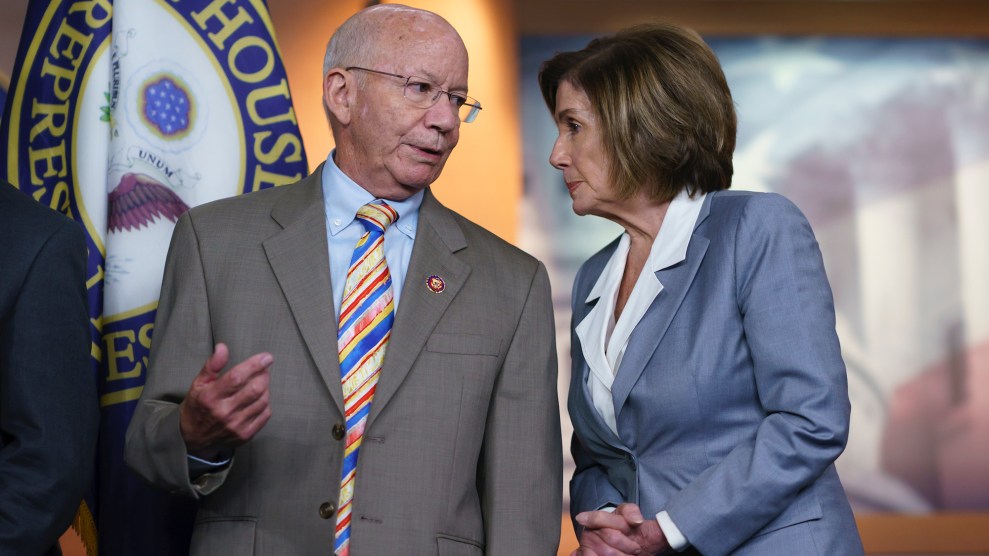

House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chair Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) in Washington on June 30, 2021.J. Scott Applewhite/AP

Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) escaped the room where the Congressional Progressive Caucus met Tuesday afternoon to declare into her cellphone: “It’s all bad news.”

This was the longtime Chicago-area lawmaker’s synopsis of where things stood on negotiations over Joe Biden’s proposed jobs and infrastructure package. For the time being, the details have been getting hashed out in the Senate, and it was Schakowsky’s colleagues down the hallway of the Capitol that caused her dismay. “Some of the numbers we’re hearing are not great,” she told me when I asked her about her phone call. The process seemed designed to “reduce the leverage of the House.”

Those concerns had been the hot topic during the meeting of Congress’ left-leaning lawmakers. Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.) described “frustrations” among her caucus members over the Senate’s process and what’s been “left out of what they’re doing so far.” Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, offered a similar synopsis. “We don’t want our Senate colleagues to forget that there’s a House of Representatives that has to also agree on all of these pieces,” Jayapal warned as we spoke after the meeting.

Many of Jayapal’s colleagues have been even more pointed in their criticisms. House Transportation and Infrastructure Chair Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) said on a private call this week that the “whole thing falling apart is probably the best thing” that could happen to the Senate’s work, Politico reported. Rep. Salud Carbajal (D-Calif.) bluntly described the Senate’s efforts as “bullshit” on that same call.

There’s long been a rivalry between Congress’s upper and lower chambers over which should take the lead on drafting bills. But at this moment, the angst is particularly acute. Congress is rushing to deliver on Biden’s ambitious economic agenda. And in the House, lawmakers are starting to worry that the Senate’s moderating effects will limit the ambition of what might be their one shot at a lasting, progressive legacy.

Some of these dynamics are by design. Late last month, a small, bipartisan group of moderate senators struck a deal with the White House on $579 billion in infrastructure spending. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) welcomed the announcement with one of her own: The House would not take up the bipartisan deal unless it arrived in her chamber alongside a budget bill, a legislative vehicle for more sweeping spending that can pass with only Democratic votes. That volleyed work back to the Senate, where a “mod squad” of bipartisan senators have been hashing what, exactly, is in that $579 billion deal, while Democrats on the Senate budget committee flesh out a $3.5 trillion reconciliation package.

The details on what’s actually in either of these deals have been scant. “I haven’t seen the bipartisan deal, other than I’ve heard it talked about,” Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) told me Tuesday. Jayapal complained that she’s “still trying to assess what’s in the climate piece, because it’s just not clear.”

What they have heard, they don’t particularly like. Much of the bipartisan infrastructure bill is being built upon legislation that passed out of various Senate committees earlier this year—ignoring the infrastructure bill the House already passed. Those bills include provisions that irk progressives, such as rollbacks to what’s called the “Magna Carta” of American environmental laws at a time when most in the party want to see even stricter rules on the books. “That really shocked me,” Chu said of those measures. “We don’t want an infrastructure bill that is worse for the environment.”

One source close to the Senate negotiations dismissed the House lawmakers’ complaints as crocodile tears. The negotiations were always going to favor the Senate, this source explained: Biden was hankering to cut a deal with GOP lawmakers, and that could only happen in the evenly split Senate. DeFazio, whose committee is overseeing the House’s infrastructure bill, was asked to join Senate negotiations earlier this spring, the source says. DeFazio—then in the process of bringing the House’s infrastructure bill to a vote—declined, saying he wanted to sort out the differences between the chambers in conference once the Senate determined its own deal. (A spokesperson for DeFazio explains the House chair was never invited to sit down with Senate Republicans, but instead encouraged to work with Senate leadership on an infrastructure package distinct from what the House was already working on.)

That House infrastructure legislation included more than $5.6 billion in funding for “member projects,” known colloquially as “earmarks,” which Democrats brought back during this session of Congress. These earmarks amount to pork for districts back home: Money for local projects that would otherwise go unfunded. And that may be what irritates House members most of all. As the Senate crafts its iteration, it threatens to leave those earmarks behind—and “defeats the purpose” of the work House members put into crafting their own package, Chu explains.

That Senate deal now teeters on the brink of collapse as lawmakers continue to quarrel over how to pay for it all. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) has scheduled a procedural vote on the bipartisan measure for Wednesday, an effort to encourage lawmakers to resolve their differences with a deadline. (The vote is expected to fail, and lawmakers are expected to continue negotiations into the weekend—but not much beyond that.)

If the deal survives and passes out of the Senate, all eyes will be on the House to see if these complaints translate into action. While most of the national focus has been on the Democrats’ razor-thin margin in the Senate, things aren’t much better in Pelosi’s caucus, where the nine-member Democratic majority could easily crumble if a handful of Democrats decide to vote against the bill. Moderate House Democrats are urging Pelosi to immediately hold a vote for the bipartisan package as soon as it passes the Senate, while progressives aim to hold the speaker to her earlier promise that it only gets a vote once the Senate passes the budget reconciliation bill.

So far, progressives have not stood in the way of legislation they disagree with, but Jayapal didn’t take that off the table. “If Republicans start taking the bipartisan bill and…put bad things in there—in order to get more Republicans—then we will lose Democrats,” Jayapal said.