Rafael Gonzales

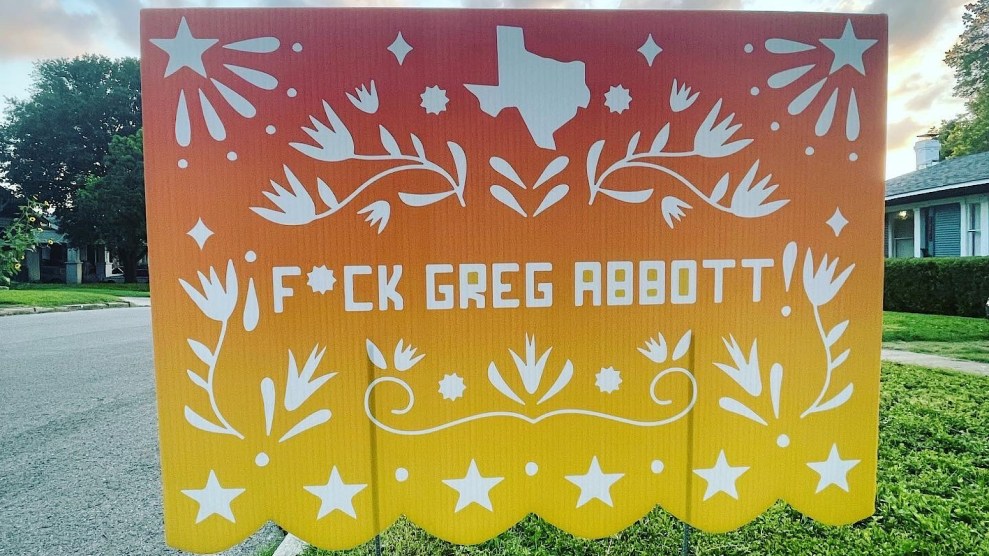

In May, after Texas passed a restrictive abortion law, San Antonio artist Rafael Gonzales Jr. decided to create papel picado. Typically, this means tissue paper banners that are placed on altars for Day of the Dead celebrations or hung as street decoration. Gonzales, instead, retrofitted the papel picado into yard signs and T-shirts with a message: “F*ck Greg Abbott.”

The phrase bashing the Texas governor has often been chanted at protests. It has trended according to Google twice in the past year. When Texas joined a wave of other Republican-led states passing abortion restrictions, it inspired Gonzales to put the phrase in his art, too. Texas’s abortion law concerned him. It allows private citizens to sue abortion providers employing a strategy some say is intended to fend off legal challenges from abortion providers. And the law is particularly restrictive. It bans abortions after six weeks.

The six week provision, Gonzales says, stirred “internal frustration” with Abbott. “It was jarring because my wife and I, a couple of years back, had a miscarriage. And we didn’t find out we were pregnant until the eighth week,” he said. “So that’s distressing because we would have, essentially, not even known that we were pregnant at that point.”

Aside from the papel picado, other pieces of Gonzales’ artwork criticize the Texas governor as he makes his pitch for a third term with split approval ratings. In an Instagram post from March, after Abbott announced the end of the state’s mask mandate while vaccinations were lagging, Gonzales added to his pandemic Loteria by releasing an image of Abbott with devil’s horns.

“It’s artwork that comes from experiences,” Gonzales says of his work. “Not so much focus on politics—although there’s an element there—but for me, it’s about what I’m living, what I see around me, and I think that’s what the largest motivation for some of my pieces are.”

These simple, cathartic expressions are what drew me to Gonzales’ artwork. His work skillfully addresses threats to Texans’ livelihoods and nods to cultural practices. And other prints—like a taco being revered as Our Lady of Guadalupe or a Valentine’s card depicting the staple meal of eggs and weenies—pull away from rage altogether and showcases Mexican American symbols with pride.

Gonzales is a 10th generation Texan. His great, great grandfather fought in the Alamo. When the state became a republic, his family was granted land in Pleasanton and donated what later became a Catholic Church. He calls himself a son of the Republic of Texas. This makes the nativist feedback—like when one person responded to his artwork by telling him to “go back to California”—particularly ironic.

“You can criticize my art all you want, but it is Texas-based. Just because Texas has this conservative, red-state type of reputation now, doesn’t mean that that’s what it is,” Gonzales said. “We have blue cities, and there’s a long history here in San Antonio of Tejanos making and being part of the culture of San Antonio, where Hispanics make up 60 percent of the population. So we’ve been here for forever.” Making resistance art doesn’t make his Texas roots any less true. In San Antonio and other major Texas cities, Gonzales actually fits right in.