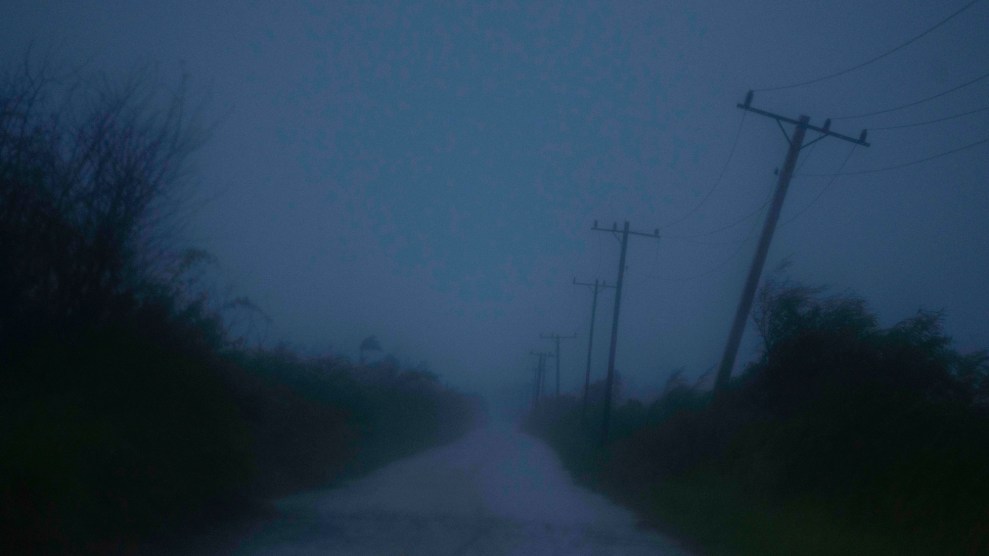

A utility pole bends from winds caused by Hurricane Ida on a road leading to Batabano, in the Mayabeque province, Cuba on Friday. Ramon Espinosa/AP

Hurricane Ida is projected to hit Louisiana on Sunday as a Category 4 storm, bringing winds as high as 140 miles an hour to the Gulf Coast 16 years to the day after Hurricane Katrina made landfall. Mandatory evacuation orders are in effect for some coastal parishes and parts of New Orleans (though evacuation is often an option that not all residents have), and the Saints have canceled their Sunday game at the Superdome. And all of this is coming as the state’s hospitals are already overwhelmed by a fourth wave of COVID-19.

Hurricanes are expected in hurricane season, but read the explanations of Ida and something else stands out: Ida is going to be a lot worse than it would have been, because the Gulf of Mexico is really warm right now.

Per Reuters:

“This storm has the potential for rapid increases in intensity before it comes ashore” because of extremely warm waters off Louisiana, said Jim Foerster, chief meteorologist at DTN, which provides weather advice to oil and transportation companies.

Per WWSB:

Ida looks to rapidly intensify…as it moves over the very warm Gulf of Mexico where water temperatures are into the upper 80′s.

At Sarasota Magazine, Bob Bunting offers a good explanation of what “extremely warm” means in this case, pointing to NOAA data (and handy maps) showing that “the Gulf is up to 8°F warmer than it should be this time of the year.” I won’t try to get into the mechanics of how hurricanes work, but suffice to say that hotter water temperatures correlate with more severe storms.

And that’s the ominous story underlying the immediate story here, because the Gulf of Mexico is getting warmer. A 2017 study of the potential impacts of warming water temperatures on Gulf storms found that the region might be due for fewer hurricanes overall, but the ones that did hit would be more damaging—specifically, “an increased proportion of category 3, 4, and 5 storms.”

Hurricanes, of course, are a longstanding thing, and the explanations for their prevalence or size are complicated. But Ida’s emergence, one year after the United States set a record with $22 billion weather events—as fires rage out west and flash floods wreak havoc in Tennessee and New York—is nonetheless an image of a future that’s already here. We are, and increasingly will be, confronted with the sorts of disasters that our existing infrastructure and routines were not set up to absorb.