Chris Piasick

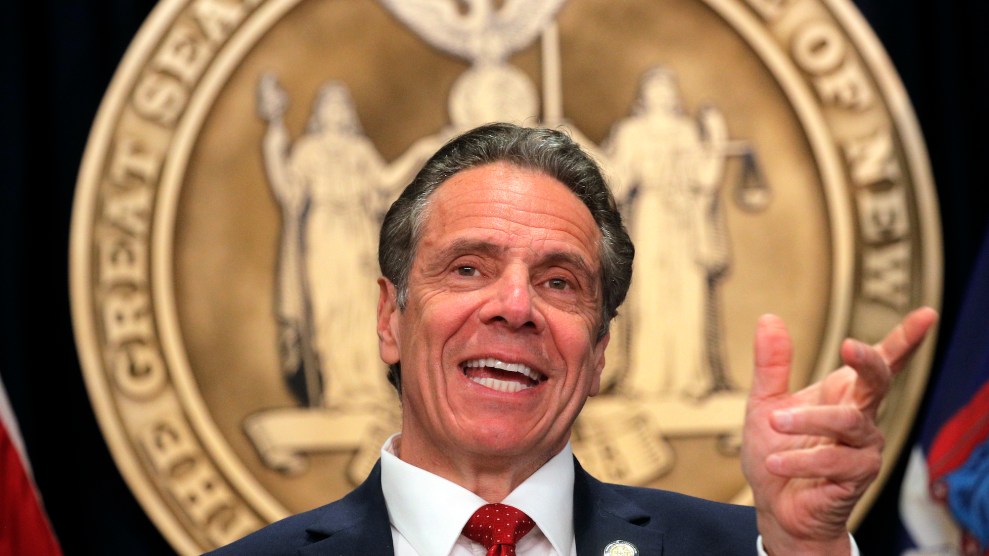

It would be hard to deny today that the male chauvinist pig is still alive and kicking, running amok in his own filth. The election of Donald Trump and his “grab ’em by the pussy” regime mixed misogyny, mockery, and race privilege with delight. Andrew Cuomo’s domineering behavior in politics echoed his sexually belittling actions in private. Both were proud of being jerks, personally and professionally, and both got called “male chauvinist pigs.”

Calling someone a male chauvinist pig offers sweet revenge, a chance to dehumanize those who dehumanized you. But the insult contains more than a laugh. The three jabs in quick succession—male, chauvinist, pig—are part of feminist attempts to place men’s sexism within a broader American political milieu. The phrase is also a prime example of how men respond to being called sexist: They think it’s funny.

Named after the (probably apocryphal) French soldier Nicolas Chauvin, who kept trumpeting Napoleon’s greatness no matter the ill treatment doled out to him, the term stands for jingoism coded as false honor.

Within the American Communist Party in the early 20th century, chauvinism was a common insult. It called out a tribal attachment—to one’s race, gender, or nationality—that distracted from class solidarity. Questions of how identity intersected with class played out among chauvinisms. Purges to rid the party of racists were discussed as ending “white chauvinism.” In complaining about sexism to Vivian Gornick in her book on American communism, one woman wondered how “not one goddamned Communist was ever thrown out for male chauvinism.” In the 1960s, as feminists—many of them red-diaper babies—created their own networks, they adopted the language to name patriarchy.

Pig was an obvious addition, an old insult for those holding corrupt power. Its historical links to racialized policing perhaps led to “pig” as a moniker for white police terror. In the post-Reconstruction South, Black Codes in some states included “pig laws,” which attempted to turn former slaves into captive laborers by penalizing minor infractions—like stealing a $3 pig—with long terms of incarceration. But Huey Newton of the Black Panther Party said it was simpler: “Pig” was chosen to show “grotesque qualities” and create a “detestable” picture “that takes away the image of omnipotence” of the white power structure.

The male chauvinist pig thus captured feminist fury as intertwined with other movements on the left: against nationalism, against racism, against capitalism, and against cops. As activist Robin Morgan explained in the underground newspaper Rat in 1968, women wanted to target “all the good old American values.” The insult did just that.

Still, there were limits to such a moniker. As feminists “quickly adopted slogans and symbols of the Black liberation movement like ‘Right On!’ and the clenched fist,” wrote Helen H. King in Ebony magazine at the time, “pig” was another battle cry that felt like appropriation. And rather than shy away from it, men began to embrace the MCP epithet as a badge of honor. Wasn’t it funny they were such assholes?

This joke’s-on-you position could be private. “You know, you’re a male chauvinist pig,” President Richard Nixon joked to his attorney general, John Mitchell, in 1971, in a secret tape, as discussions of how to nominate a woman to the Supreme Court drifted into casual sexism. Or it could be public. Like the buffoonery of tennis champ Bobby Riggs, whose iconic battle of the sexes with Billie Jean King pitted a fun-loving playboy against the all-too-serious feminist: “I don’t mind being called a male chauvinist pig,” Riggs said, “as long as I’m the No. 1 male chauvinist pig.” This embrace of what was meant to be derogatory rendered the real complaints of women unserious. By the 1990s, Rush Limbaugh proudly called himself a pig. He could take a joke; why couldn’t the women he called “feminazis”?

Cuomo similarly dismissed his female accusers as humorless, allowing him to frame his own actions as benign. Cuomo’s political demise may indicate that this tactic no longer works, that the chauvinist pig has been put in his place. But then again, they say Trump could run in 2024.

Julie Willett is a professor of history at Texas Tech University and author of The Male Chauvinist Pig: A History.