Travis Scott performing at his Astroworld festival.Photo by Erika Goldring/Getty

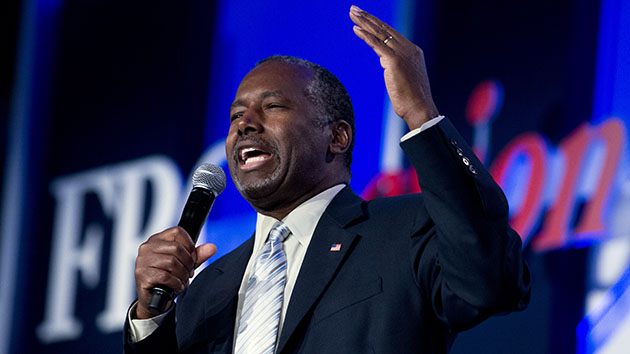

“Look what just happened at a Travis Scott concert!” yelled Greg Locke, a Pennsylvania pastor, as he paced on stage to appreciative murmurs from his congregation. “If you think that was an accident, you are not paying attention. If you look at the stage setup, if you listen to the lyrics, this was not a mishap in a field in Houston. This was a satanic ritual, 100 percent,” he continued to escalating applause and cheers.

You might already be aware of what Locke is pedaling. After hundreds of people were injured and eight died at Travis Scott’s seemingly severely mismanaged Astroworld music festival in Houston, conspiracy theories about how the deaths were somehow part of a sacrifice ritual abounded on social media. People on Twitter started posting QAnon-esque numerology about Scott. On Tik-Tok, where the Locke video received over 100,000 views, others kept calling Scott’s set-design a “portal to hell” and dredging up supposed Illuminati references in his lyrics.

Journalists and disinformation analysts, justifiably, lamented the vortex—a mini-redux of the 1980s Satanic Panic, blended with QAnon residue. But it also was reminiscent of something else: almost every other moment of major, or even middling, social and political upheaval and change in recent years.

The election, the January 6 Capitol riot, the coronavirus vaccine, the coronavirus generally, vaccines generally, fireworks being distributed in cities as a government plot, saving the children, etcetera, etcetera. Each, just like Scott’s concert, has inspired a conspiratorial response. Most of that is just from the past 12 months. If you want to think back just a tiny bit further, there are loony claims about laser beams starting fires in California, 5G technology, George Soros funding a migrant caravan, and false flag attacks.

Conspiratorial theories aren’t necessarily incited by a specific incident. Someone can just post something weird online and people will run with it, like the false accusation that Wayfair trafficked children in armoires. Many such theories have layered and bleed together in what Anna Merlan described in Vice as a “conspiracy singularity: the place where many conspiracy communities are suddenly meeting and merging, a melting pot of unimaginable density.” Merlan wrote those words to make sense of what was happening early on the in the pandemic, but since then the trend has both persisted and worsened.

The woman who shared the video of Pastor Locke on Tik-Tok also maintains an Instagram page, stuffed with posts about other conspiracies: QAnon-adjacent claims about missing children, chemtrails, flat-earth talk, and the like. While that might sound like behavior coming from the antisocial fringe, beyond a preoccupation with conservative politics, the rest of her recent feed shows a normal mix of kids, hobbies, and a life beyond the internet.

But if you scroll years back, you can see that at the outset of the pandemic she pretty much exclusively posted on her family and exercising and nutrition hobbies. It was more recent that she began to slide into posting more right-wing political—and often conspiratorial—claims.

That tracks with wider trends, as the coronavirus and its societal fallout not only helped rekindle QAnon, which had been briefly fading, but also served as an accelerant for conspiratorial thinking more broadly. This phenomenon was explained neatly by artist and internet researcher Josh Citarella in a recent episode of his podcast: “The pandemic was an incubation period for people who are already on the borderline stuff. And then content consumption goes way up. Social atomization goes was up. Economic precarity spikes…and well, people who are on the borderline are now radicalized.”

As conspiracy theories have become a lingua franca among certain sets, allowing them make order out of disorder–particularly the chaos and economic disruption of the pandemic, more and more conspiracists look like the woman who posted the video of Pastor Locke—relatively normal people moving through the world and then going online and posting surreal things. Conspiracy theories are just now the logic that many default to—and for the time being, the rest of us have to deal with it.

Pushing back won’t always make a difference. “They meant for those people to die and they ain’t the least bit sorry about it. I don’t care what they say on Twitter,” Locke said at the end of the video about Scott, perhaps anticipating criticism of his beliefs from that site’s younger, left-leaning users. The congregation applauded.