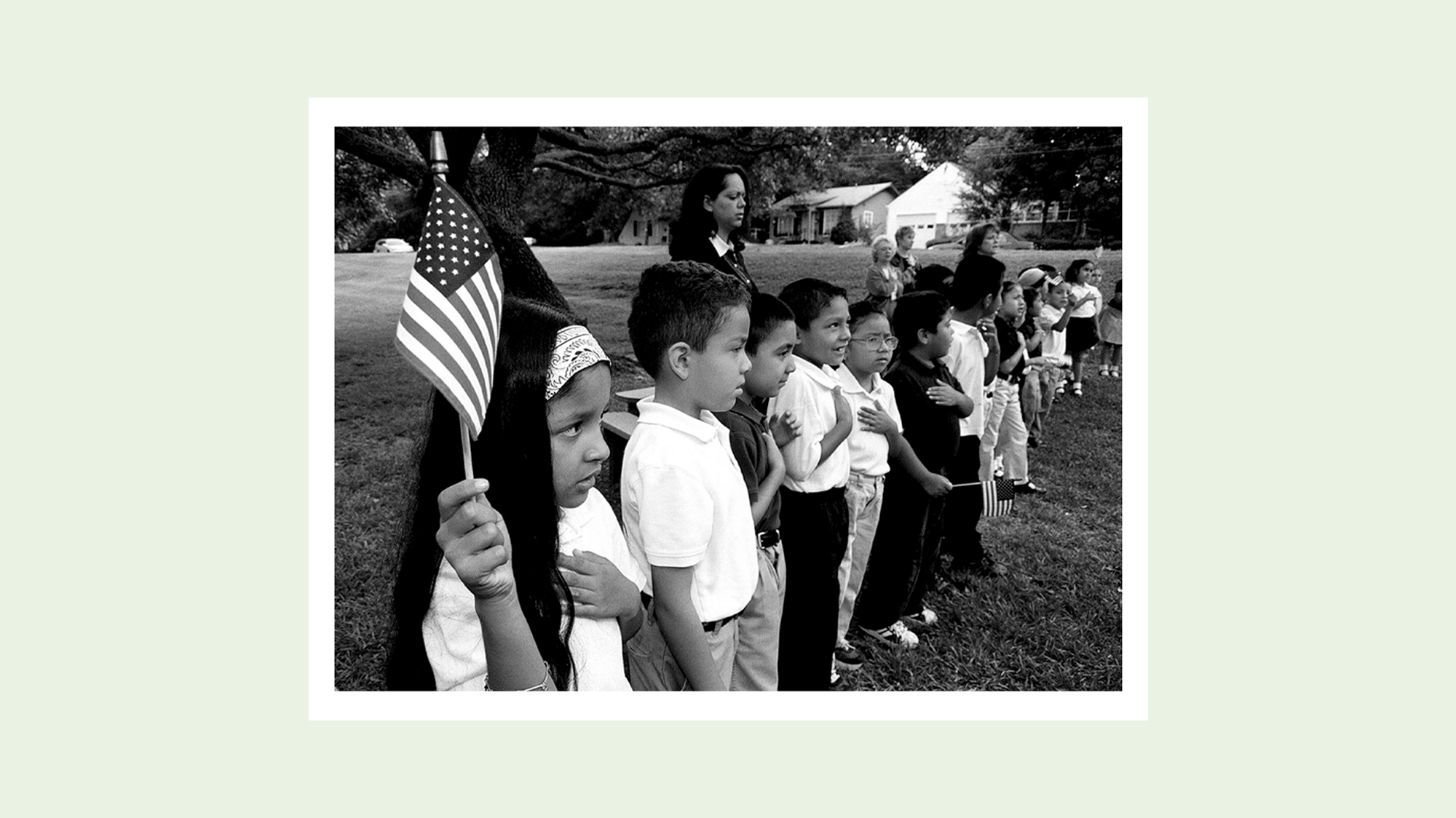

On August 31, 1977, Rosario Robles walked her five children to Bonner Elementary School in Tyler, Texas. Rosario and her husband, Jose, had immigrated to the United States from Mexico five years earlier and settled in the “rose city” southeast of Dallas, where Jose found work at a local pipe factory and the family bought a house. But never before on the first day of school had Rosario been asked to present proof of legal residency for their children—American passports, for instance, or birth certificates issued by US hospitals. When she couldn’t, the school’s principal denied the children admission, even driving them home in his own car.

Also in Tyler, Humberto Alvarez, a Mexican-born father of four children enrolled in Douglas Elementary School, was told that the Tyler Independent School District would charge undocumented students an annual tuition fee of $1,000 per student, or the equivalent of roughly $5,000 today. Alvarez, who had left his home country in 1974 and started working at a meatpacking plant in Tyler, couldn’t afford the fee, so the requirement effectively excluded his children from the school system. Basically, the statute allowed for different school districts and schools to implement different policies.

These new policies came in the wake of the Texas legislature voting to amend the Education Code with a section, known as 21.031, that withheld state funds from public school districts for the education of children who had not been “legally admitted” into the country. The statute allowed districts to deny enrollment to foreign-born children without legal status, or to charge them tuition. Other school districts in Texas, including the state’s largest district of Houston, implemented similar practices. In Tyler, the school district board of trustees justified the policy as a way to “prevent the potential drain on local educational funds should Tyler become a haven for illegal aliens.” Jim Plyler, the superintendent of Tyler schools at the time, referred to the children as a “burden,” even though only about 60 of the 16,000 enrolled students lacked legal status.

In September 1977, the Robles, the Alvarez, and two other families filed a class-action lawsuit against Plyler arguing the Texas statute violated their constitutional rights. The plaintiffs had been living in Tyler for anywhere between three and 13 years in mixed-status households, where their US-born children who were citizens weren’t barred from school, unlike their Mexican-born siblings. The families were represented by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), a national Latino legal civil rights organization. As University of Houston Law professor Michael A. Olivas (who died in April 2022) wrote in his 2012 book, No Undocumented Child Left Behind: Plyler v. Doe and the Education of Undocumented Schoolchildren, MALDEF’s national director of education litigation, Peter Roos, and the group’s president, Vilma Martinez, considered the case to be the “Mexican American Brown v. Board of Education.”

The group of plaintiffs inspired sympathy: Undocumented children who weren’t responsible for their parents’ decision to migrate, with parents who worked. They also had an ally in William Wayne Justice, a federal judge who was both revered and reviled in rural Texas for his liberal views and for having ordered desegregation in Tyler schools in 1970. On September 14, 1978, Judge Justice ruled that the state’s reasoning that the statute would relieve the school district from a financial burden and regulate immigration was irrational and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

By 1980, most districts in the state had implemented practices excluding undocumented immigrants. In July 1980, a federal judge in Houston deciding on the combined cases arrived at a similar conclusion as Judge Justice. The two parallel lawsuits moved separately through the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the lower court’s rulings, before being consolidated as Plyler v. Doe, which the Supreme Court heard on December 1, 1981.

On June 15, 1982, in a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the students and established that all children without reference to their immigration status have the constitutional right to a public K–12 education. “By denying these children a basic education, we deny them the ability to live within the structure of our civic institutions, and foreclose any realistic possibility that they will contribute in even the smallest way to the progress of our nation,” Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote in the majority opinion. “It is difficult to understand precisely what the state hopes to achieve by promoting the creation and perpetuation of a subclass of illiterates within our boundaries, surely adding to the problems and costs of unemployment, welfare, and crime. It is thus clear that whatever savings might be achieved by denying these children an education, they are wholly insubstantial in light of the costs involved to these children, the state, and the nation.”

Peter Schey, the president and executive director of the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law Foundation in Los Angeles, had been the lead counsel in the consolidated statewide class-action lawsuit and went on to argue the case before the Supreme Court, sharing time with MALDEF’s Peter Roos. When news about the 1982 Supreme Court decision broke, he was on a trip to Nicaragua to document human rights abuses committed by the Contras, a US-backed rebel group opposing the Sandinista socialist government. Listening to BBC News on the radio with his delegation as they sat around a campfire when the broadcaster announced the historic decision by the Supreme Court, Schey jumped up screaming, “We won! We won!”

In building his case before the lower courts, Schey brought in expert witnesses such as child psychiatrists who could testify about the harmful impact of school exclusion on the learning progress and development of the students, and criminal justice scholars who warned of a potential increase in juvenile crime if kids were pushed out of the classroom. Two young girls who had been affected by such policies also described their experiences to Judge Woodrow Seals of the Southern District of Texas in Houston, who heard the case. After 24 days, Judge Seals decided in favor of the children, writing, “It is possible to perceive the impact of the creation of a permanent underclass of persons who will live their lives in this country without being able to participate in our society.”

The ruling represented a victory in what had been an uphill battle for Schey and his team, since they were fighting on behalf of 100,000 or more children—a much larger number than had been covered by the earlier Tyler case. “The fact that one could win a case in a very small school district where the impact of enrolling children would be relatively minimal would not answer the question of whether the law was irrational on a statewide level,” Schey says.

The two favorable rulings, which the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld, were promising, but the fact remained that while the appeals from Texas were pending, the children kept missing out on school. Schey filed an emergency request with the Supreme Court to vacate a stay blocking the immediate enrollment of the children, which the court granted. “It was one of the most important cases I had handled in terms of the impact on thousands and thousands of innocent children,” says Schey. “We were just very lucky. All Texas needed was one more vote and over 100,000 children would have had their lives destroyed.”

Despite the split decision, even those who voted in the Supreme Court justices agreed that the Texas statute constituted bad public policy. “Were it our business to set the nation’s social policy, I would agree without hesitation that it is senseless for an enlightened society to deprive any children—including illegal aliens—of an elementary education,” Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote in his dissenting opinion. “However, the Constitution does not constitute us as ‘Platonic Guardians’ nor does it vest in this Court the authority to strike down laws because they do not meet our standards of desirable social policy, ‘wisdom’ or ‘common sense.'”

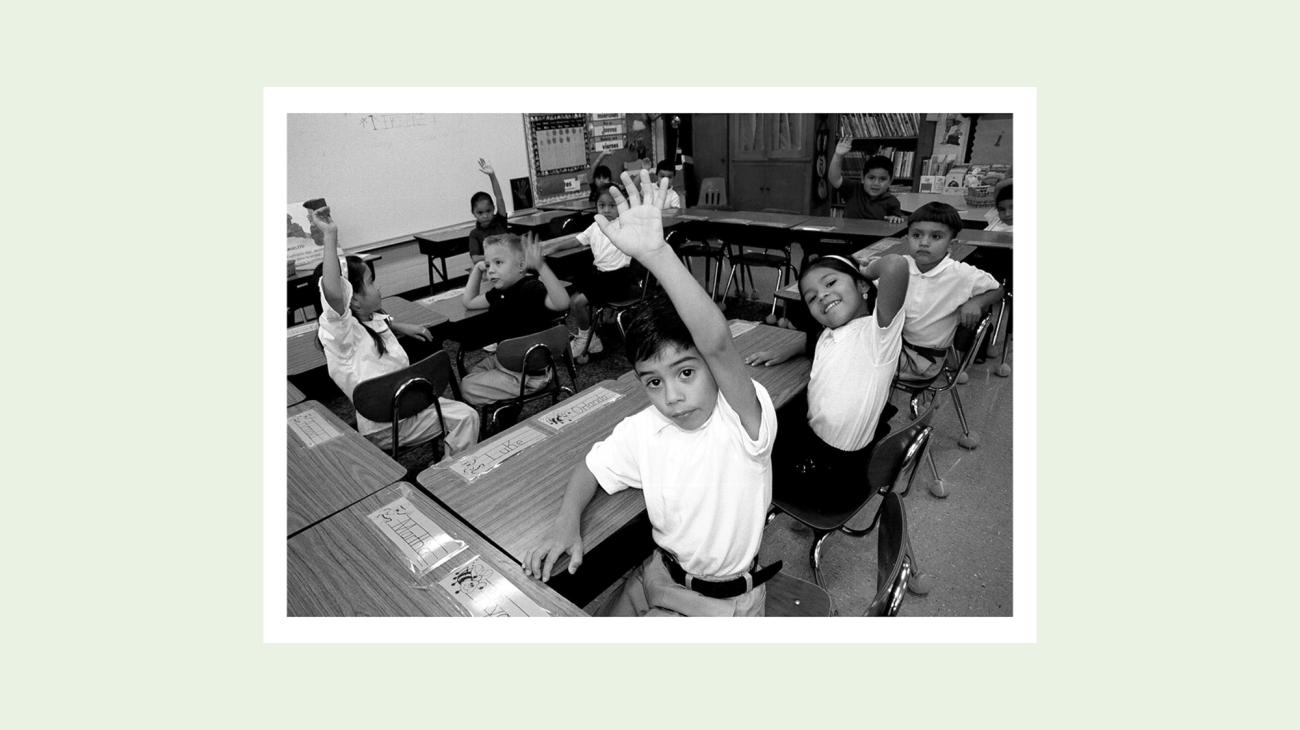

Monolingual Hispanic students raise their hands to answer a question during a class taught in Spanish at Birdwell Elementary School in September 2003 in Tyler, Texas.

Mario Villafuerte/Getty

During the 40 years since the Plyler decision, there have been direct and indirect attempts to undermine it, most recently by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas, where it all began. In a May interview with the conservative radio program The Joe Pags Show, Abbott said, “Texas already long ago sued the federal government about having to incur the costs of the education program, in a case called Plyler v. Doe and the Supreme Court ruled against us on the issue. I think we will resurrect that case and challenge this issue again, because the expenses are extraordinary. And the times are different than when Plyler v. Doe was issued many decades ago.”

Immigrant activists and educators immediately repudiated Abbott’s statement, some characterizing it as nothing more than an empty threat aimed at scoring points with voters. “He was throwing out a political dog whistle to appeal to the extreme right who might believe he would really attempt to implement the policy,” says Thomas Saenz, MALDEF’s president and general counsel. “I don’t really believe that Governor Abbott would ever follow through on his threat to attempt to reverse Plyler. No governor really wants thousands of kids on the street, instead of in school, and any politician who precipitates that occurring is doing so at tremendous risk to their political future.”

The governor may have felt emboldened by the impending overturn of Roe v. Wade by the current Supreme Court conservative supermajority. But unlike the landmark 1974 case that guaranteed the constitutional right to have an abortion, Saenz says, Plyer has actually been codified into federal law by Congress in 1996. “Before you even get to whether the Plyler precedent was correct or not, you have a federal statute that is, in effect, a congressional endorsement of Plyler,” he says. “So they would first have to explain why that statute doesn’t prevent them from violating Plyler even before you get to the Plyler decision behind it. It’s a double barrier that wasn’t present in 1982 and that doesn’t exist in Roe v. Wade.”

Attempts to challenge Plyler abounded over the years but haven’t survived legal challenges. One of the most egregious attempts took place in California in 1994, when then–Republican Gov. Pete Wilson campaigned for reelection on the infamous anti-immigrant Proposition 187, also known as the “Save Our State” initiative (which some political analysts credit with helping turn California blue). Prop. 187 would have barred undocumented immigrants from attending public schools and accessing non-emergency health care. Voters approved the ballot measure by almost 60 percent, but the courts blocked the implementation of most of it largely based on the Plyler precedent.

Two years later, Republican Rep. Elton Gallegly of California introduced an amendment to a series of immigration laws known as the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which would allow states to deny public education to undocumented students or charge them tuition—a direct attempt to overturn Plyler v. Doe. The Gallegly amendment passed the House, but President Bill Clinton vowed to veto the bill over its inclusion, and the amendment ultimately was withdrawn.

In 2011, Alabama enacted legislation requiring schools to collect information about the legal status of students and report it to the state. The provision was struck down in court, but it was part of a larger strategy to undermine the right of undocumented children to access public education. As one of its authors, Michael Hethmon, an attorney with the Immigration Reform Law Institute, a legal arm of the anti-immigration Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), later admitted to the New Yorker Times, the goal was to force litigation in the hopes of sending the Plyler case back to the Supreme Court so it would be overturned. That same year, Arizona’s Senate President Russell Pearce proposed an unsuccessful measure requiring proof of citizenship for children to enroll in schools and banning undocumented students from attending state universities and community colleges. Pearce, who had been one the architect of some of the country’s toughest anti-immigration laws, was recalled from office in 2011 in large part over his crackdown on immigrants.

During Donald Trump’s presidency, Stephen Miller, his senior adviser and the mastermind behind the president’s draconian anti-immigrant policies, sought to circumvent the 1982 ruling. Miller reportedly pushed White House officials to consider issuing a guidance memo giving states the option to deny undocumented students enrollment in K–12 schools. At the time, a spokesperson for the Department of Education said “the memo wasn’t issued because the Secretary would never consider it.”

As recently as late 2021, Bruce Griffey, the Republican state lawmaker in Tennessee who recently called pro-vaccine legislators “medical Nazis” and sponsored a “Don’t Say Gay” bill, introduced legislation to withdraw state funds from public schools for students who are “unlawfully present” in the United States. Saenz estimates his organization receives calls every year about school clerks asking for social security numbers to enroll kids, a clear violation of Plyler. “The fact still is,” he says, “that excluding these kids from school is much more costly to society and to the government than the cost of providing education.”

In the years since, scholars and legal analysts have disagreed on the merits of Plyler and the significance of its legacy. In 1983, Chief Justice John Roberts, then a lawyer for the Reagan administration, strongly criticized the decision, suggesting the Department of Justice should have filed a brief siding with the state of Texas and against the children. When asked about it years later in his 2015 Supreme Court nomination hearing, Chief Justice Roberts evaded questions about whether he had come to agree with the decision and if he considered it to be settled law. “I haven’t looked at the decision in the Plyler v. Doe in 23 years,” he said.

Law professors have argued that because no state other than Texas had a law in the books at the time excluding undocumented students, the decision merely impacted an “outlier statute.” But it’s easy to imagine that had it not it been for this precedent, several other states might have followed Texas’ lead. “The pressure was tremendous,” Roos told NBC News recently. “I was confident in our case, but there was a sense that if we lost, other states would pass laws like Texas. So the outcome could affect millions of kids, and that was a heavy weight on my shoulders.” In his book The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind, Yale law professor Justin Driver writes, “It is difficult to identify many opinions in the Supreme Court’s entire history that have more profound consequences in more vital arenas than Plyler v. Doe’s guarantee that the schoolhouse door cannot be closed to one of modern society’s most marginalized, most vilified groups.”

Olivas, author of No Undocumented Child Left Behind, agreed, writing, “The opinion has single-handedly enabled innumerable children to use education to expand both their minds and their horizons.” Plyer “may be the high-water mark of immigrant rights in the United States and is likely among the most important educational and immigration cases decided in Texas.”

In determining that undocumented children could not be punished for their parents’ actions, the Supreme Court decision also created the legal foundation for President Barack Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—a program enacted exactly 30 years after the Plyler decision that has granted relief from deportation and work authorization for hundreds of thousands of undocumented young people who came to the United States as children. As Olivas observes, it is a simple causality: “If there were no Plyler, there could be no undocumented college students.”

By holding that undocumented immigrants can assert a claim to equal protection under the 14th Amendment, the Supreme Court also created a precedent that has been cited, for instance, in challenges to Trump’s failed attempt to exclude immigrants from the Census. Schey says the case also provides “future protection to vulnerable populations who are discriminated against by a state or the federal government when that population has no responsibility for the status that is the basis for their discrimination.” In 2007, Jim Plyler, the Tyler school district superintendent, told Education Week he was “glad we lost the Hispanic [court case] so that those kids could get educated.”

The Los Angeles Times tracked down the “children of Plyler” for a story in 1994. Most of them had finished high school in the Tyler Independent School District. Years later, they became legal residents or citizens as a result of the 1986 immigration reform legislation that conferred status to millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States. Laura Alvarez, who hadn’t known she had played a role in the case until the newspaper contacted her, worked for years as a teacher’s aide for the same Tyler district that had excluded her years earlier.

“As a result of that decision there’s no question several million children later became permanent residents and then citizens of the United States, have received an education,” says Schey, “and have gone on to become productive members of their communities.”

An alternative scenario in which that wasn’t the case would look more like what Carola Suárez-Orozco, a Harvard Graduate School of Education professor in residence and immigration expert, described a hypothetical trajectory of two siblings, one who was born in Honduras and the other in the United States. One would have no education while the other “would be entitled to attend school as a citizen. The siblings would experience the consequences of a Solomonic decision,” she says, “played out in countless iterations, for a situation they had no role in creating.”