This article was published in partnership with the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the US criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletters, and follow them on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

Eastern State Penitentiary, a former prison turned museum in Philadelphia, used to lure in visitors every Halloween with an event called “Terror Behind the Walls.” The haunted house, with evil doctors, a jailbreak, and zombie inmates jumping out to scare visitors, was one of the museum’s most lucrative fundraising events. But starting last year, the museum decided to drop the gore and emphasize the educational. Now the event is more optical illusions, eerie soundtracks, and live performances focused on the museum’s mission of highlighting issues of incarceration.

Museum curators debated the appropriateness of the haunted house over the years. Sean Kelley, Eastern State’s senior vice president and director of interpretation, said he had grown uncomfortable with the use of prison scenes in the haunted house. “I’m amazed at how numb many of us can be about these sites. The whole subject of incarceration is less a source of amusement than it was 10 years ago in America, but there’s still like a layer of people thinking that it’s funny,” he said. “But it’s not funny to us.”

Prison tourism often relies heavily on the spooky, the gruesome, and the salacious to attract visitors for a playful afternoon of ducking into cells and taking selfies in striped jumpsuits. But the entire industry, built largely on entertainment at the expense of incarcerated people’s dignity, is grappling with a growing criminal justice reform movement—and the business is being challenged by questions about exploitation and voyeurism.

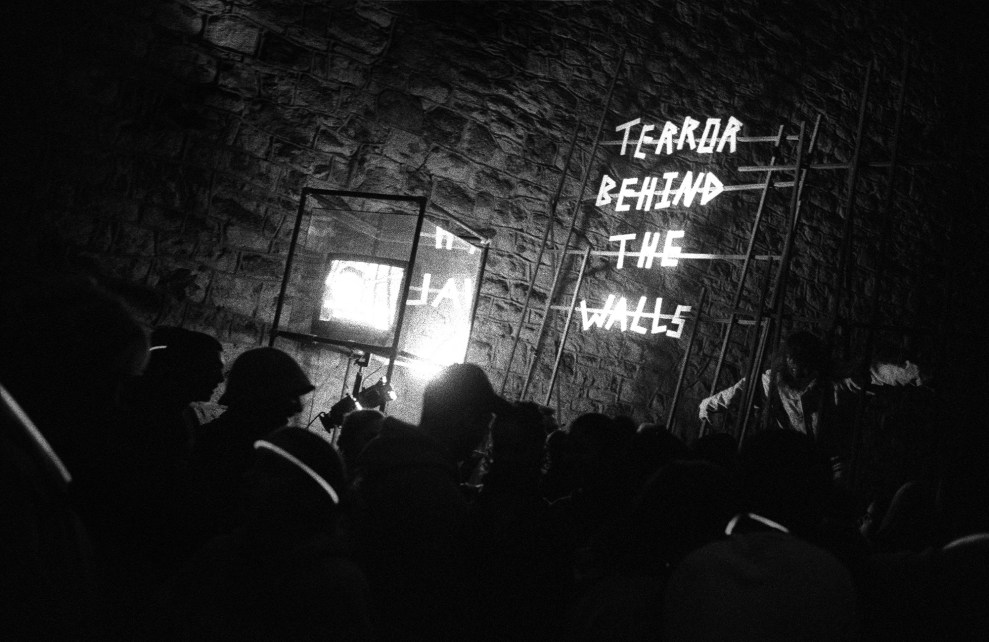

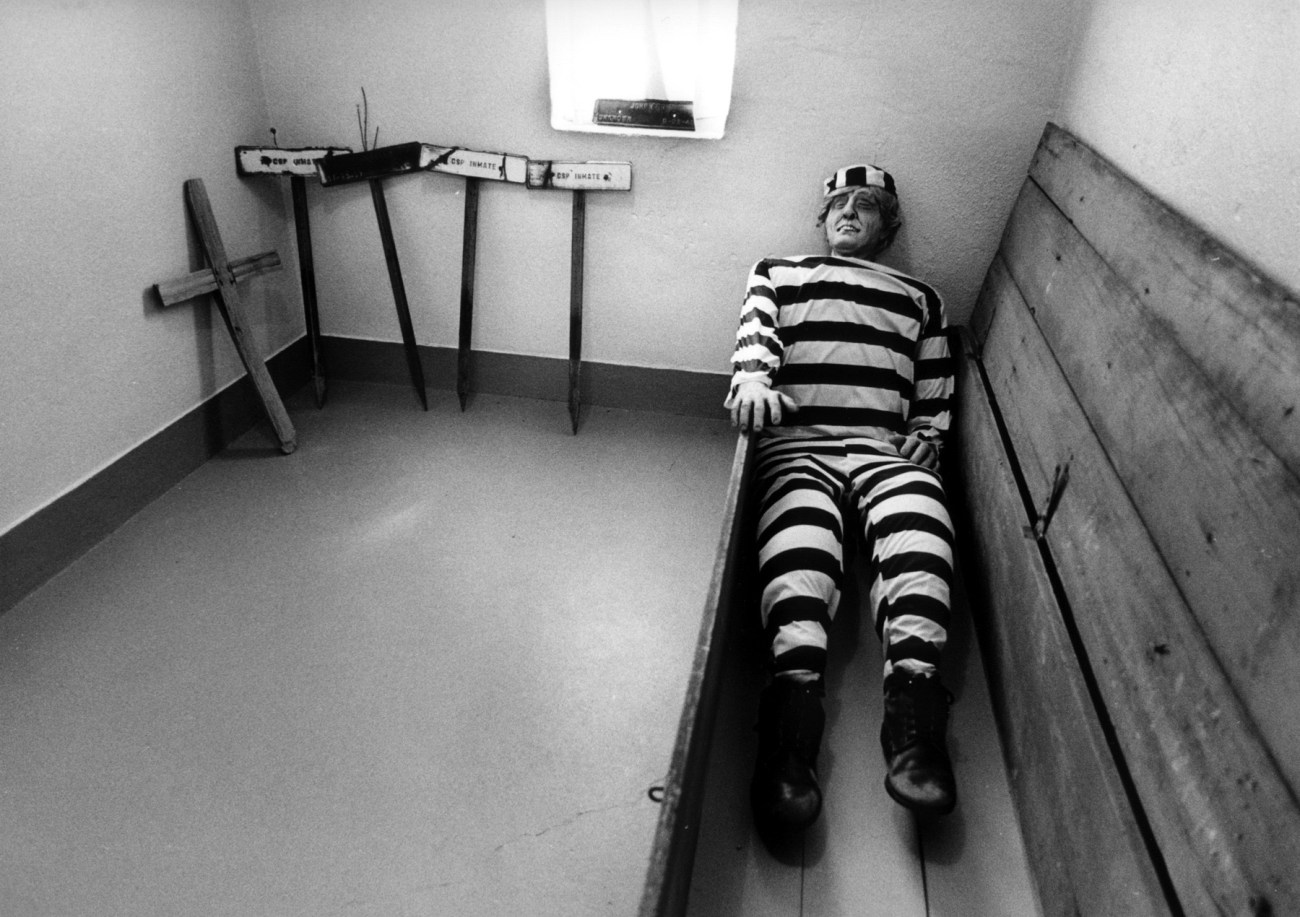

Terror Behind the Walls haunted house at Eastern State Penitentiary.

Terror Behind the Walls haunted house at Eastern State Penitentiary.

Some prison museums are less scholarly history than grotesque spectacle. At the West Virginia Penitentiary, visitors can sit in a defunct electric chair, and play “Escape the Pen,” an escape-room style game where players have a one-hour “stay of execution” granted by the governor to escape death. On the penitentiary’s TripAdvisor page, there are pictures of smiling children sitting in the electric chair. (Tom Stiles, the tour director, said that the West Virginia Penitentiary tour “does not try to disrespect an inmate or an inmate’s life. It does not try to disrespect the institution itself. We tell historical facts.”) The Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City encourages visitors to take photos in the facility’s old gas chamber used to execute 40 inmates, over half of whom were Black. The facility offers an eight-hour overnight ghost tour, asking attendees if they can survive the night on “the bloodiest 47 acres in America.” Texas Prison Museum, where the gift shop sells branded “Solitary ConfineMINTS,” displays nooses, images of a lethal injection execution, and a defunct “Old Sparky,” and lets visitors pose for pictures in a replica prison cell.

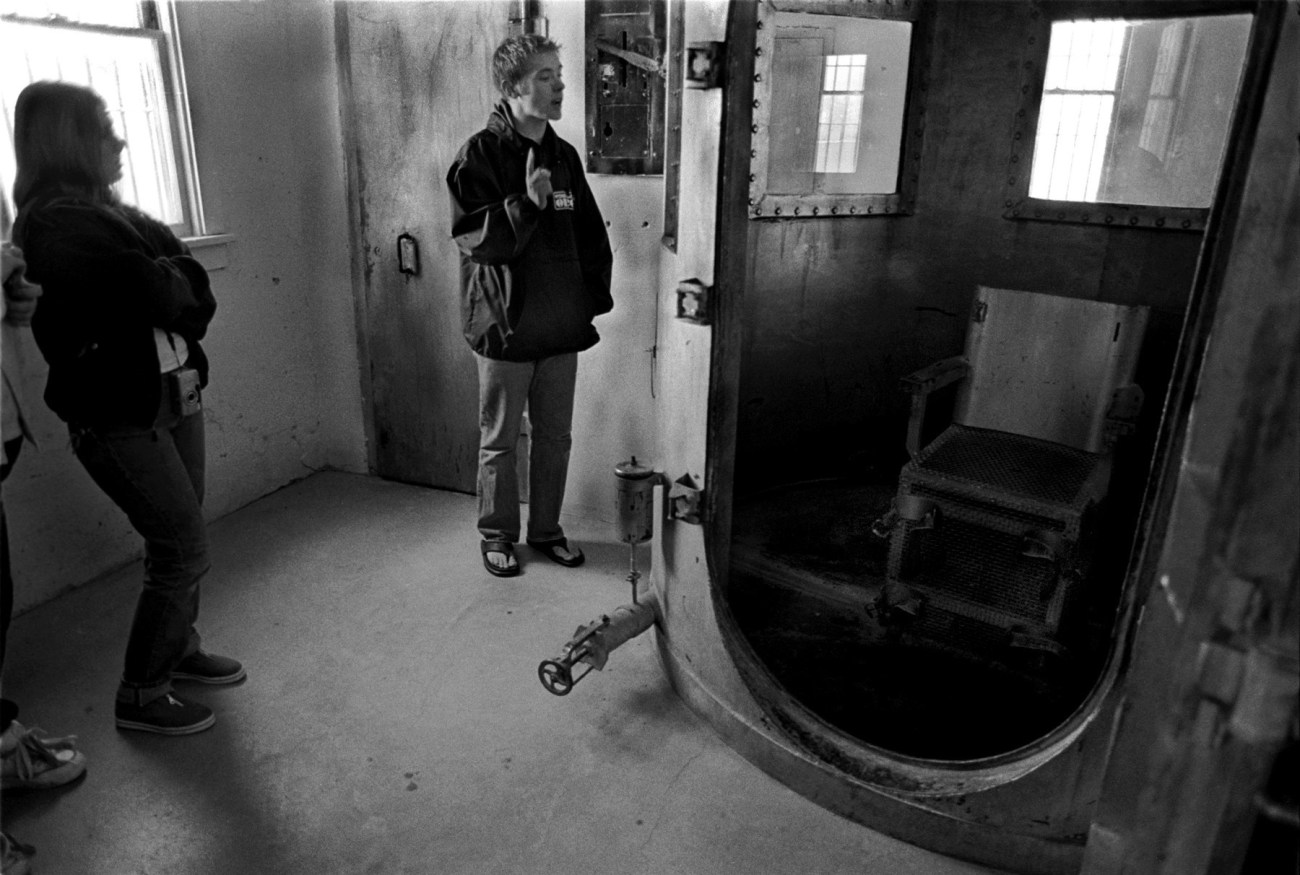

Gas chamber at Wyoming Frontier Prison.

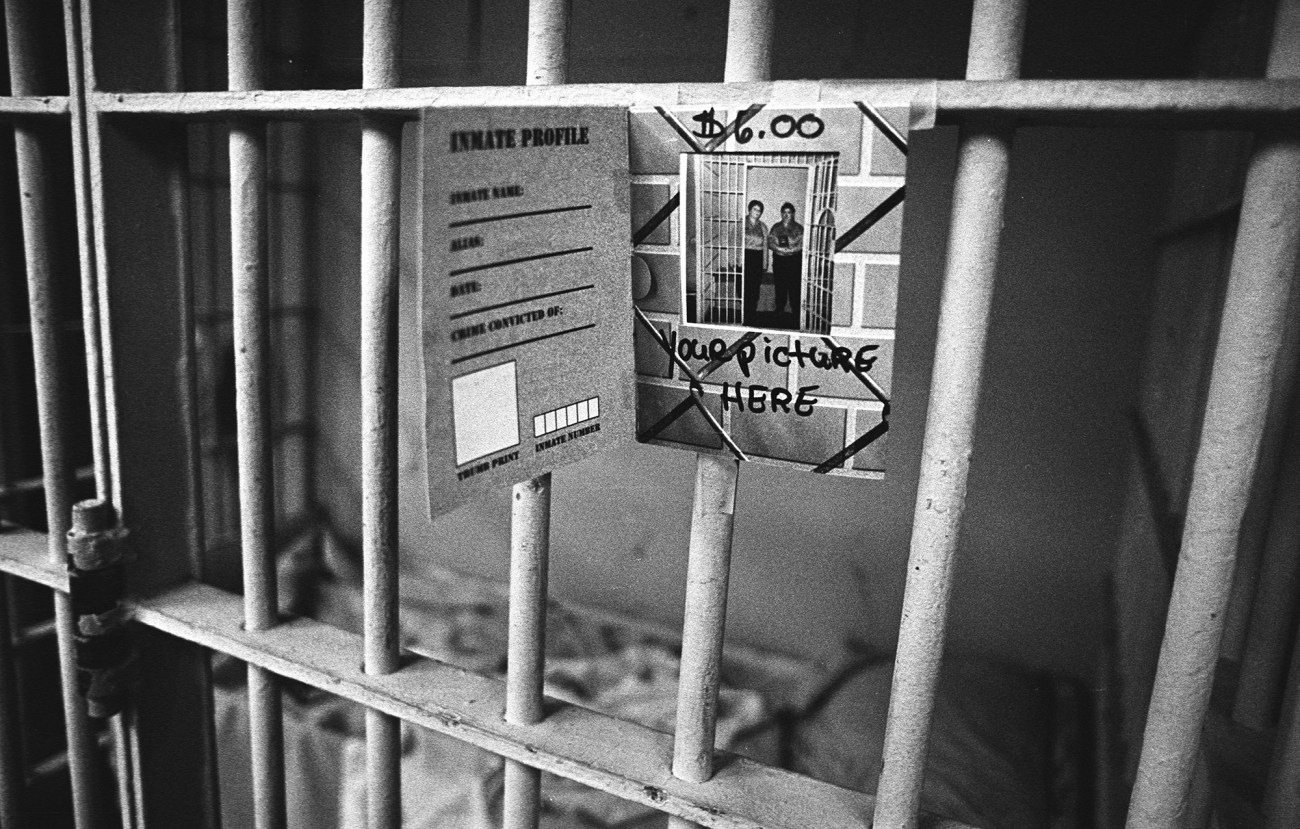

West Virginia Penitentiary

In historian Clint Smith’s book How the Word Is Passed, he recounts his visit to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, a prison built on a former slave plantation. Upon entering, he is greeted by a disturbing image of a white man on horseback overseeing a group of Black men working in a field. The photo hangs in a gift shop that sells Angola branded t-shirts, shot glasses, and koozies that say “Angola: A Gated Community.” Smith writes that he looked around the gift shop, wondering whom it was attempting to serve: “Who saw the largest maximum-security prison in the country as some sort of tourist destination?”

In addition to the prison tour and museum gift shop, Angola operates an annual prison rodeo, in which incarcerated men with no prior training compete for the entertainment of thousands of visitors. The most dangerous event is the Poker Game. Officials release a bull into an area where Incarcerated men are seated at a table; the last man seated at the table is awarded $500. The 2022 rodeo sold out in April. (An Angola spokesperson said the museum is a separate nonprofit from the prison or the Department of Corrections and “exists to provide a historical record of the prison’s past and present,” and that the voluntary prison rodeo “offers a unique opportunity for incarcerated persons to spend time with their friends and loved ones outside of regular visitation.”) Prison tourism extends to hospitality as well. In Boston, the Liberty Hotel occupies the site of the former Charles Street Jail, which once imprisoned suffragists and civil rights activists, including Malcolm X. In the 1970s, a judge found conditions in the jail so horrible that they were inhumane. Today, guests staying at the luxury hotel can receive a tour of the jail with a complimentary glass of champagne, and dine at the restaurant, Clink, and the bars, Alibi, and Catwalk, set on the former jail catwalk.

West Virginia Penitentiary

A child grabs a noose at the Wyoming Frontier Prison in Rawlins, Wyoming.

“The way the United States approaches prison tourism re-inscribes the kind of politics that support mass incarceration,” said Jill McCorkel, a professor of criminology at Villanova University. “It turns human suffering into a spectacle.” To her, the “gold standard” of prison tourism sites are Robben Island in South Africa, where Nelson Mandela was incarcerated, and Kilmainham Gaol, a former prison in Dublin, Ireland, for their thoughtful depiction of the sites’ history.

Over the past several decades, interest has surged in mass incarceration as a humanitarian cause, fueled by exploding prison populations and outbreaks of deadly violence—from the 1971 Attica prison uprising to the current chaos at New York’s overcrowded Rikers Island jail complex. In some ways, the changing tone of prison tourism sites reflects the shifting public perception of the stresses and inequities of the penal system. It is part of a broader rethinking of how we memorialize the past, from Civil War statuary and former slave plantations to lynching sites and concentration camps.

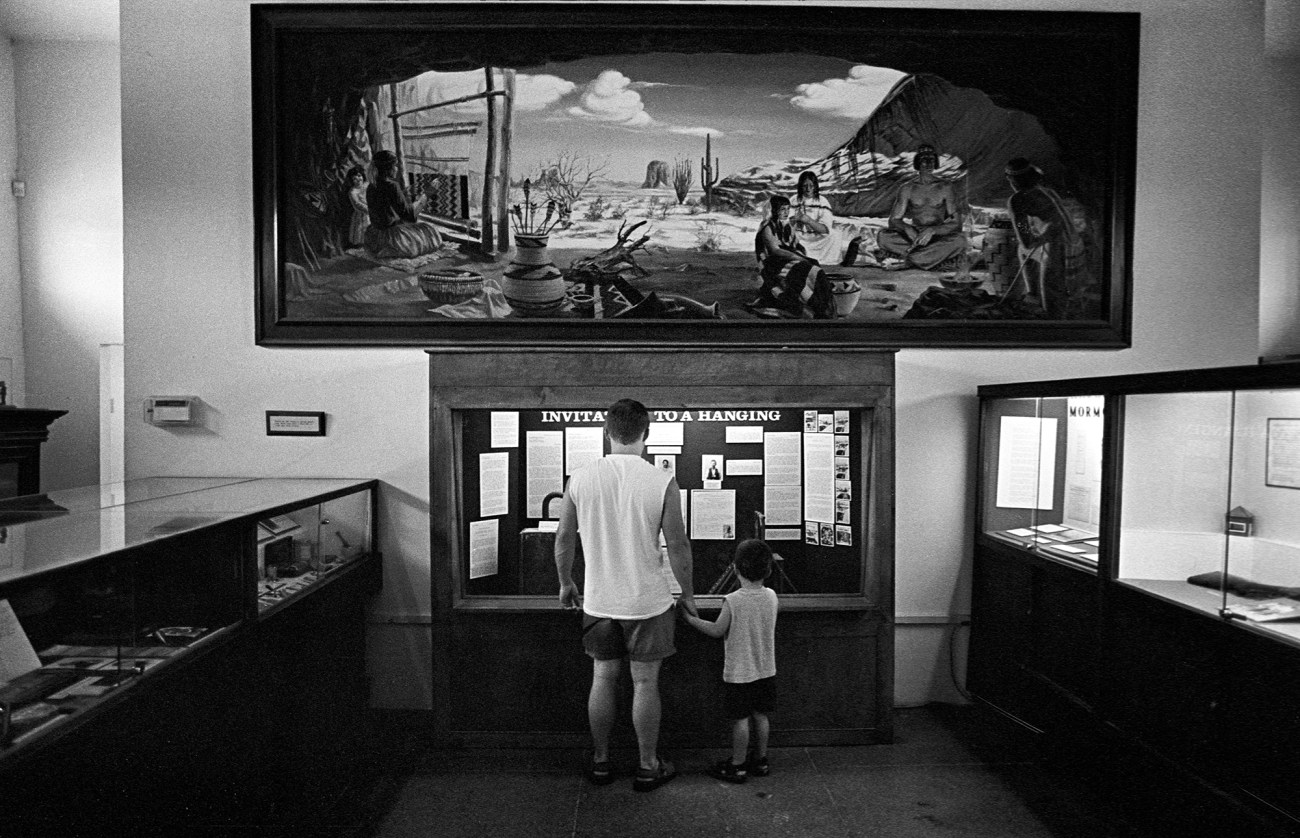

Colorado Prison Museum, Cañon City, Colorado

Prison burial exhibit, Colorado Prison Museum.

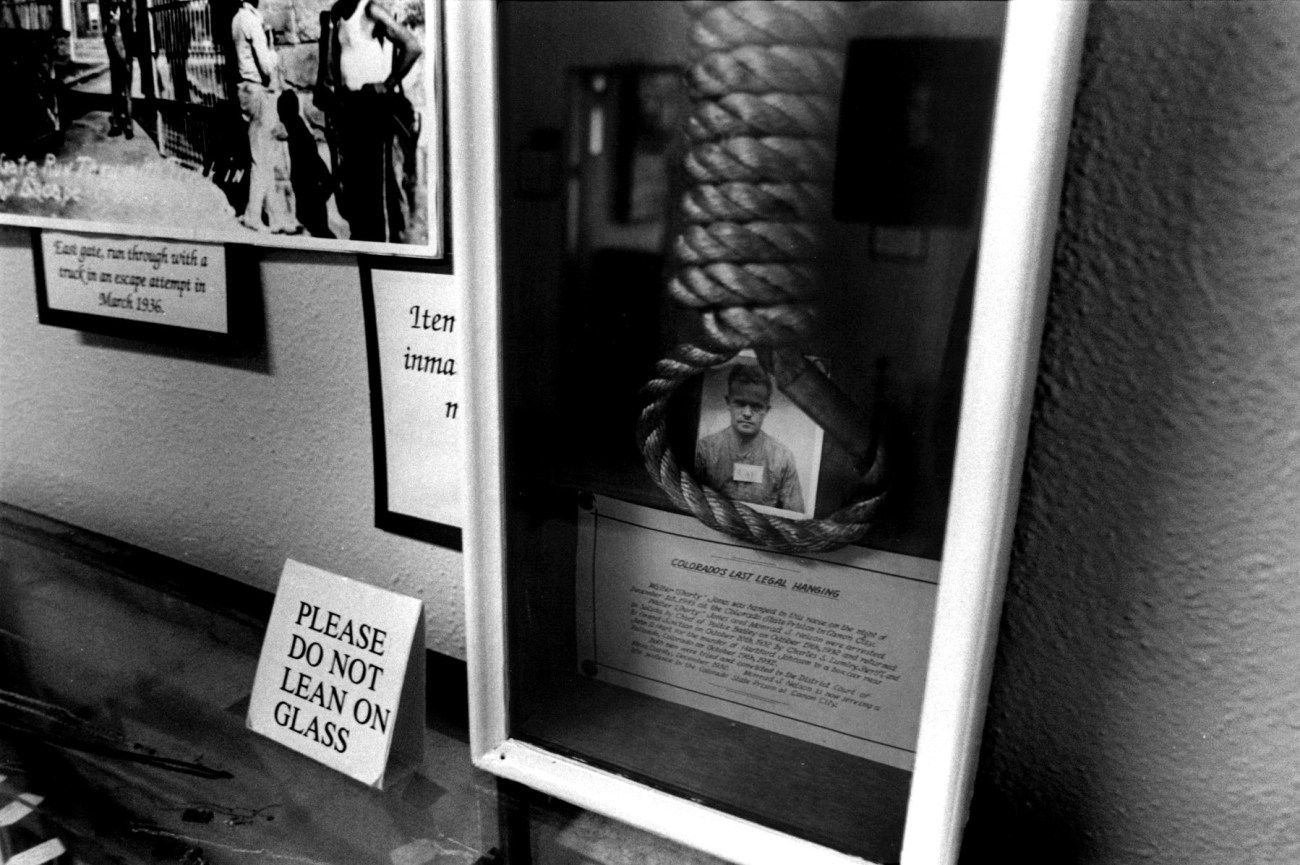

Last legal hanging, Colorado Prison Museum.

A new prison museum is in the works adjacent to the still-operational Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York. Brent Glass, the executive director of the forthcoming Sing Sing Prison Museum, says that Sing Sing’s history represents “every chapter in America’s criminal justice history.” Opened in 1826, Sing Sing is one of the best-known prisons in the country. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed there, the Yankees have played exhibition baseball games against incarcerated men, and Warner Brothers Studios has used the prison as a film locale.

The fact that Sing Sing still houses over 1,500 men complicates the ethics of building a museum designed to tell the prison’s history while thousands of incarcerated men and their families are still living that history. Glass says the museum has been designed in conjunction with formerly incarcerated people and their families, taking into account any sensitivities that might arise.

“We’re not at all interested in pandering to voyeurism. And we’re not interested in exploiting, as some museums do, the paranormal interest,” Glass said. “We think this story is compelling enough and interesting enough as a human story, a story of history, and a story of encouraging people to imagine a more equitable justice system.”

Last year, Alcatraz introduced an exhibit called The Big Lockup: Mass Incarceration in the United States, designed to “tell untold stories important to our nation’s history concerning the complex issue of incarceration.” The Fauquier History Museum at the Old Jail in Warrenton, Virginia, has a new exhibit that focuses on the runaway enslaved people who were held in the jail and how the jail was a barrier to freedom for many enslaved people in the 19th century. The museum director told The Washington Post that he wants to “eliminate some romanticism about old jails and prisons.”

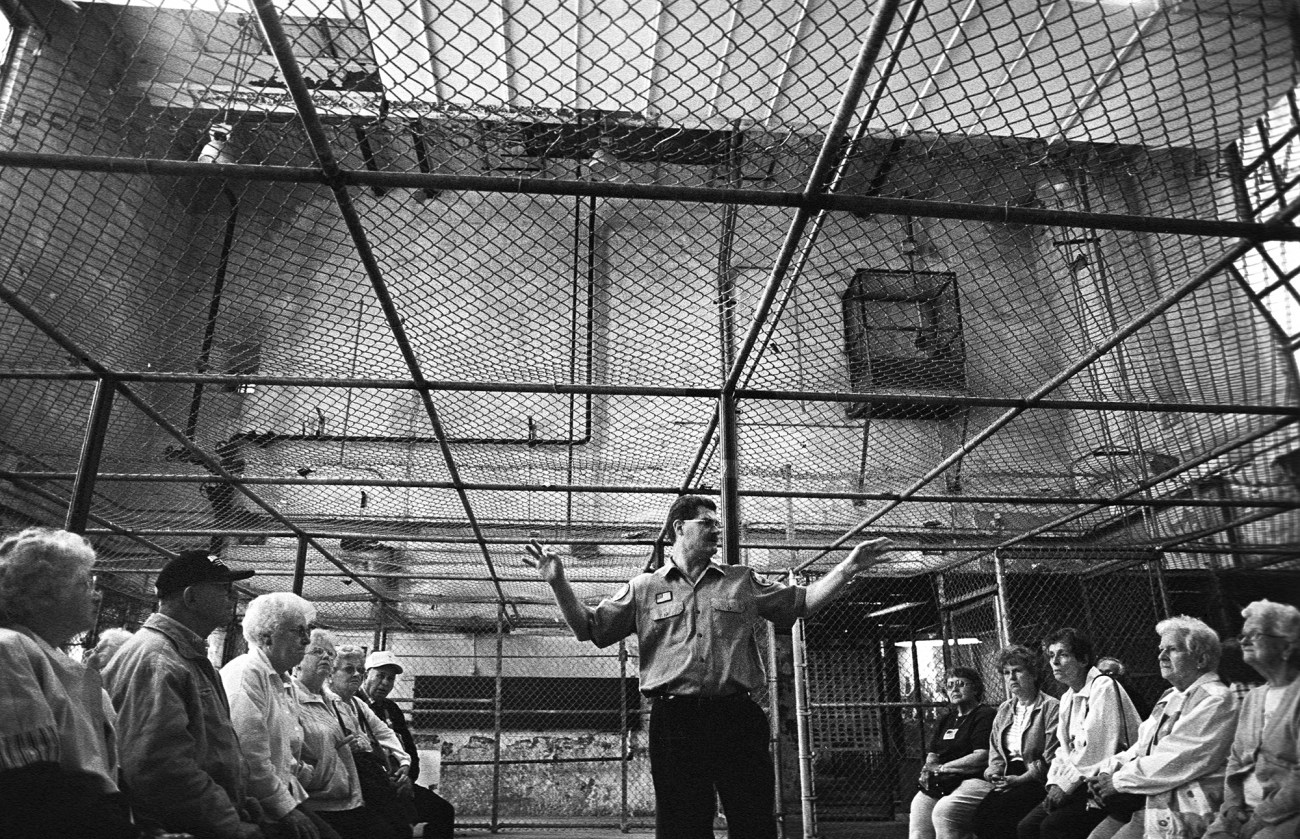

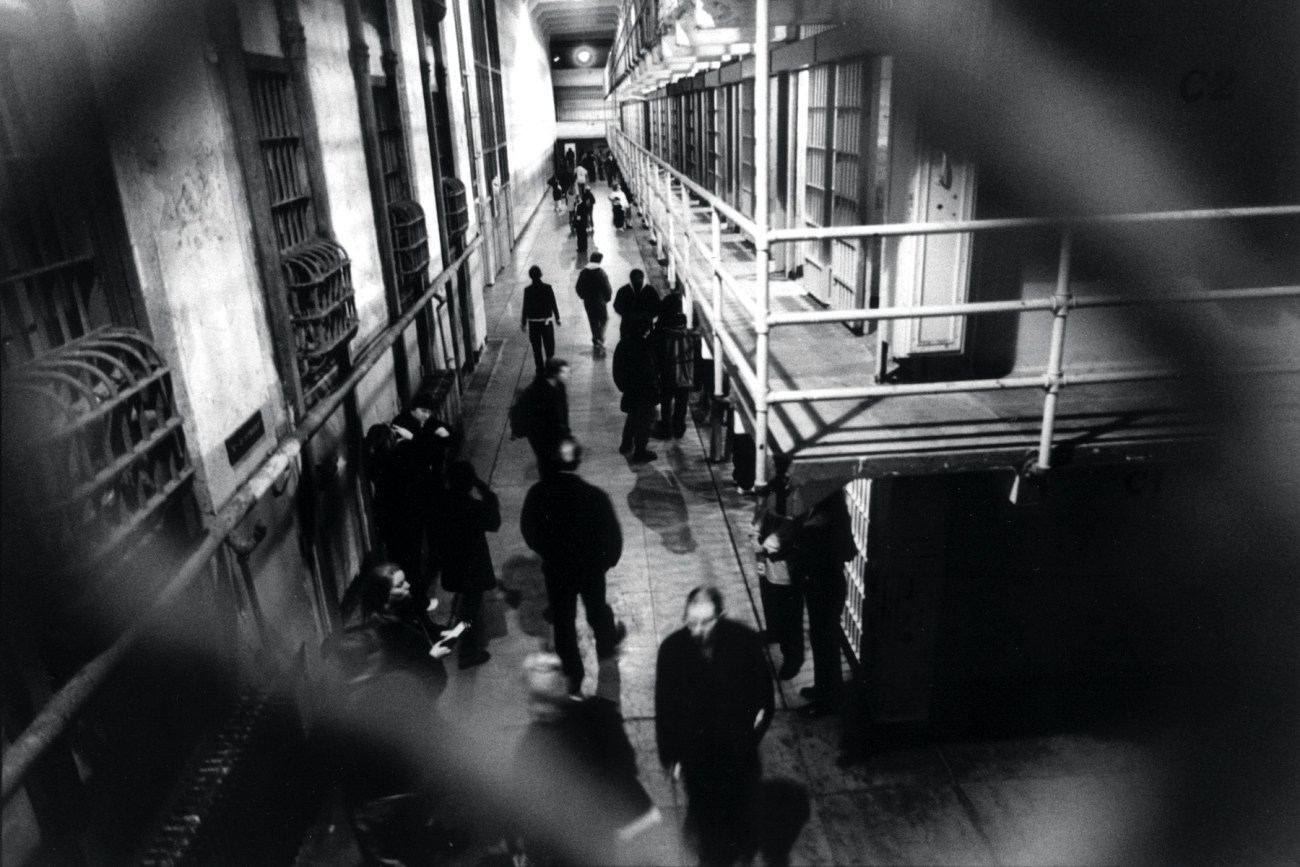

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary

Confiscated shanks, Eastern State Penitentiary.

The seriousness with which Eastern State Penitentiary handles the subject matter sets it apart from most prison tourism sites. A timely art installation engraved on the glass encasement of the prison’s greenhouse illustrates the case of Doris Jean Ostreicher, an heiress whose illegal abortion and death led to the imprisonment of the bartender who performed the abortion, Milton Schwartz. What once was the hospital ward now holds an exhibit on diseases in prison, from tuberculosis to AIDS to Covid-19. Photos and narration from both incarcerated people and correctional officers tell the story of the prison in the 20th century.

One thing a visitor learns on a two-hour self-guided audio tour of the Eastern State Penitentiary is that the United States prison system faces the same problems it did when the cells of the old prison were full: the spread of disease, gang violence, isolation, mental illness, and the disproportionate number of incarcerated Black and brown people. Many correctional facilities still don’t have air conditioning and heat. During the narration on the ESP audio tour, a formerly incarcerated man recounts being told by correctional staff upon his release that “they’ll see him in six months.” Last year, a formerly incarcerated man told me that correctional staff at his facility said upon his release that “they’ll leave the lights on for him.” What prison tourism can show us is how far we haven’t come.

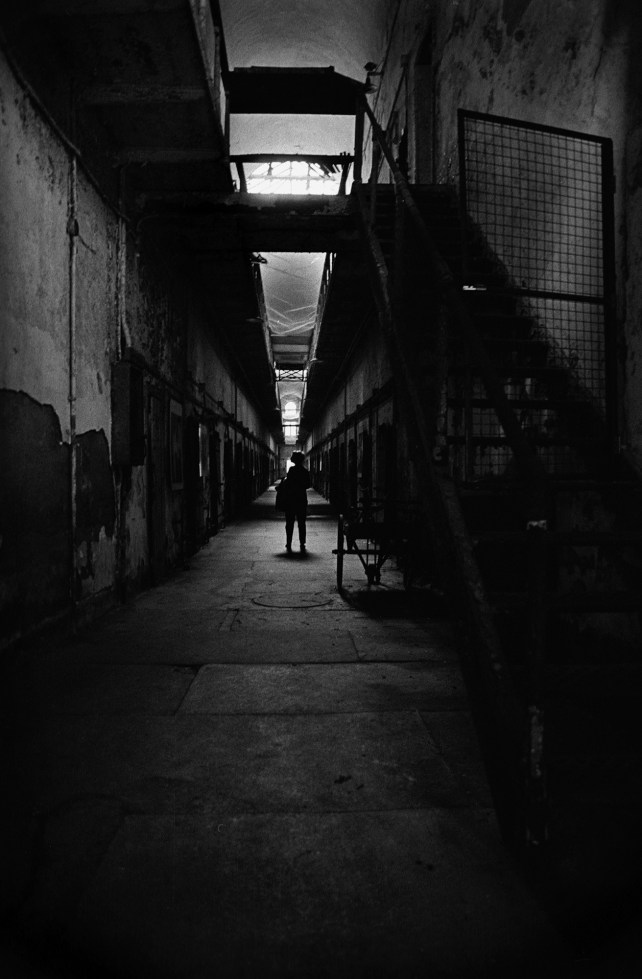

Eastern State Penitentiary

At the end of the audio tour at Eastern State Penitentiary, a 16-foot steel sculpture called “The Big Graph” offers a visual representation of mass incarceration in America. It illustrates the racial breakdown of prison populations since 1970 and charts other nations’ rates of incarceration compared to the United States. (The US sits far above the rest) The exhibit called “Prisons Today: Questions in the Age of Mass Incarceration” was added in 2016 in an effort to contextualize the impact of Eastern State Penitentiary and US prisons.

Eastern State’s Sean Kelley teaches a Zoom class to incarcerated men at SCI Chester in Pennsylvania and during one recorded class, the men shared their thoughts about prison museums. Robert S., an incarcerated man at SCI Chester, said he doesn’t have a problem with prison museums, but organizers should make sure that people have an understanding of the effect on the people who were housed there. “The museum is for amusement, but this was someone’s pain,” he said. “This was someone’s struggle. This was someone’s life. It wasn’t amusement to them.”

Yuma Territorial Prison