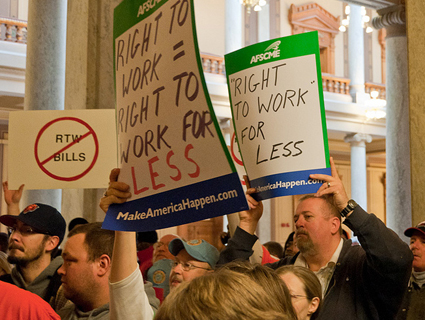

Michael Brochstein/AP

In the last decade, anti-union “right-to-work” laws have proliferated in Republican-led states. Late last week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) reintroduced a bill that would ban these types of laws, in an effort to bolster unions’ power to push for higher pay at a time when household incomes are struggling to keep up with record-high inflation.

“Republicans and their corporate interest backers have imposed state laws with only one goal: destroy unions and discourage workers from organizing for higher wages, fair benefits, and safer working conditions,” Warren said in a press release. “At a time when labor unions are growing in both size, popularity, and delivering real wins for workers, Democrats are making clear that we stand in solidarity with workers everywhere, from Starbucks baristas to Google cafeteria workers and everyone in between.”

Twenty-seven states have right-to-work laws on the books which prohibit unions and employers from requiring workers to pay fees to a union. In practice, this means that workers who reap the benefits of being represented by a union can still decline to support the union’s work financially. This deprives unions of the funds they need operate—weakening their power to bargain for better conditions on behalf of their members.

The Nationwide Right to Unionize Act would compel states to undo these provisions, paving the way for more robust union organizing. The bill is cosponsored by a slew of other democratic senators, and by Rep. Brad Sherman (D-Calif.), who is shepherding the House version of the bill. If passed, it is unclear if it could undo all right-to-work provisions, however, thanks in part to a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that created something akin to a right-to-work provision for the public sector—finding that government workers can’t be made to pay certain union fees even when benefiting from union representation.

Several studies have found that worker wages suffer in right-to-work states. A 2011 Economic Policy Institute (EPI) paper found that wages in these states were 3.1 percent lower, after controlling for outside economic factors, like higher cost of living in some states. A study from EPI five years later found that the decline in union power in the US was tied to a decrease in wages of up to 8 percent. A analysis from Rep. Sherman’s office found that in 2020, annual wages in right-to-work states were about $11,000 less on average than in states that don’t have this kind of union-weakening legislation.

Warren has tried twice before to pass versions of this bill, to no avail—first in 2017 and then in 2020. Across that same time period, the number of states with right-to-work laws has grown by almost a quarter: from 22 states in 2011 to 27 today. This same ban on right-to-work laws is also included in the Democrats’ broader bill aimed at labor law reform: the Protecting the Right to Organize Act.

Their federal legislative efforts may intersect with several ballot measures aimed at right-to-work measures in November’s midterm elections. Illinois’s ballot includes a measure that would amend the state’s constitution with a clause protecting collective bargaining and preempting future efforts to enact a right-to-work law. The opposite idea is on this year’s ballot in Tennessee: a measure that, if passed, would permanently enshrine the state’s right-to-work law by adding it to the state’s constitution.