Former president Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva during the closing rally of his presidential campaign in São Paulo. Allison Sales/AP

During a vacation earlier this year, a stranger, who later said he was a real estate agent, approached me on a beach in an upscale section of Rio de Janeiro. “What did you think of Joe Biden?” he asked in polished English. I demurred. My interlocutor then went on to tell me that the people of Brazil would never allow Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the former president better known as Lula, to return to office. He appeared to be drawing a distinction between the inhabitants of Brazil and the “people of Brazil”; the “people” were whiter, property owners, and, like their current president Jair Bolsonaro, deeply nostalgic for the days of right-wing military dictators.

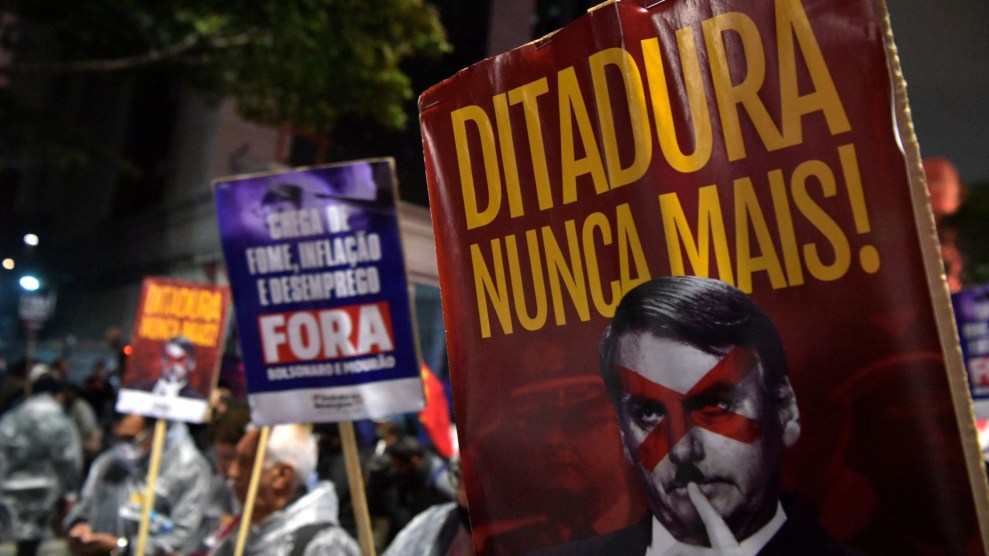

On Sunday, Brazilians all over the world are voting in the first round of a presidential election that pits Lula against Bolsonaro. Lula is the favorite, a status he’s maintained throughout the race. It’s possible that he will win outright in the first round. If not he will almost certainly face Bolsonaro in an October 30 runoff. But like his ally Donald Trump, Bolsonaro has falsely claimed that the country’s electronic voting machines are plagued by fraud and has suggested he won’t accept defeat.

Polls signal a commanding lead for former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Sunday’s election in Brazil, which may signal the return of the world’s fourth-largest democracy to a leftist government after four years of far-right politics led by incumbent Jair Bolsonaro. pic.twitter.com/gJoRuXM5vI

— The Associated Press (@AP) September 30, 2022

Lula represents the citizens of Brazil who have long been excluded from power. He is the seventh child of illiterate farmers from the country’s more impoverished northeast. As a child, he and his family migrated south, where he worked as a street vendor and shoe shiner, according to an official biography summarized by CNN. He then became a metalworker and a union leader.

After the end of the country’s military dictatorship, which lasted from 1965 to 1984, Lula mounted three unsuccessful runs for president before finally winning in 2002. He went on to take a more pragmatic approach than fellow Latin American leftists like Hugo Chávez. Through a combination of smart policymaking and good timing, the country’s economy thrived. Twenty million people left poverty and three times more Afro-Brazilians began attending university, the Los Angeles Times noted. By the end of his presidency, the Economist had Rio’s Christ the Redeemer statue rocketing skyward under the headline “Brazil takes off.” Barack Obama dubbed Lula “the most popular politician on Earth”

In 2016, five years after leaving office, Lula was charged as part of a corruption scandal that he argued was politically motivated. In 2018, he was ordered to begin serving a 12-year sentence. The following year, the country’s Supreme Court ordered that he be released after it was revealed that Sergio Moro, the conservative judge in his case, had collaborated with prosecutors. (Moro had become Bols0naro’s minister of justice before resigning and mounting a failed presidential bid against his old boss.)

“They did not imprison a man. They tried to kill an idea,” Lula declared after his release. “Brazil did not improve, Brazil got worse. The people are going hungry. The people are unemployed. The people do not have formal jobs. People are working for Uber—they’re riding bikes to deliver pizzas.” After the Court annulled his convictions last year, he became eligible to run for president again.

Before his presidency, Bolsonaro, a retired military officer, served in the lower house of Brazil’s Congress. In 2016, he voted to impeach Lula’s successor Dilma Rousseff. He devoted his vote to “the memory of Colonel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, the terror of Dilma Rousseff.” Rousseff had been imprisoned and tortured during the military dictatorship; Ustra was a convicted torturer who led an infamous Army intelligence unit during the period.

As president, Bolsnaro sped up deforestation in the Amazon, was widely criticized for his handling of the pandemic, and made clear that his fascistic tendencies remain unreconstructed. In doing so, he attracted the support of far-right leaders across the world.

More recently, Bolsonaro has tried to convince his supporters that the election could be rigged against him and has used the military to support his claim that the voting process is susceptible to fraud. His rhetoric is particularly dangerous in light of Brazil’s recent history. A recent New York Times headline put it: “The Question Menacing Brazil’s Elections: Coup or No Coup?” As my colleague Isabela Dias reported on Friday, there has already been violence:

The upcoming presidential elections in my home country are the most fraught and hate-filled in recent memory. In July, one of the president’s followers fatally shot a local Worker’s Party treasurer at his Lula-themed birthday party. Even before the official kick-off of the campaign in August, pro-Lula protesters were bombarded with feces and urine. On September 7, the day Brazil commemorated 200 years of independence, in the midst of a political discussion, a Bolsonaro supporter killed a Lula supporter, stabbing him 70 times and attacking him with an axe. This month, a researcher with Datafolha, one of the main polling institutes in Brazil, was assaulted. In a Rio de Janeiro bar, a 19-year-old woman was struck in the head after a Bolsonaro fan threatened to hit her sister when she criticized the president. Almost 70 percent of Brazilians surveyed in a September poll said they fear being victims of politically motivated violence.

“One thing is certain about this election: President Bolsonaro will only accept one result: victory,” Camilo Caldas, a constitutional law professor at St. Jude University in Sao Paulo, told Reuters. “Any other result will be contested.” We’ll soon see how far Bolsonaro and those who consider themselves to be the real “people of Brazil” are willing to go.