Mother Jones Illustration; Getty

Billy Wooten has been running elections in Georgia’s Chatham County for about 25 years. First, as a poll worker; then as a trainer for other poll workers; and now as the county’s board of elections supervisor.

For the most part, his instructions for the 15 or so poll workers who showed up for an October 14 orientation weren’t that different from years past: He always explains how to work the technology, how to respond when a voter shows up at the incorrect polling location, and what to do with the bags of ballots at the end of election night. But increasingly, Wooten, 67, has had to supplement his training with tips on how to respond to election-integrity skeptics, and especially the ones who have signed up to become poll watchers.

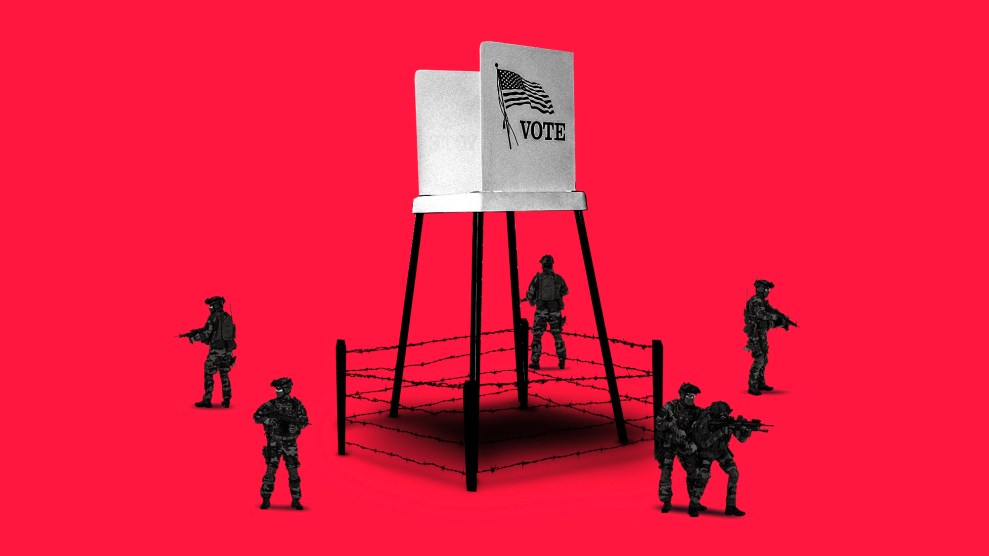

Political parties and candidates recruit official poll watchers, who have to follow state laws regulating their training and conduct at election facilities. There are also unofficial activists who take matters into their own hands, regulations aside. This year, far-right partisans have been particularly bold, setting up cameras to monitor ballot drop boxes and guarding them while donning tactical gear in various corners of the country.

“This is a contentious time in elections,” Wooten, in his deep southern accent, admits to his crew. “Some people might decide they’re gonna be trouble.”

The federal government is throwing resources at the problem. “We have been working year-round with state and local officials to share timely information and resources, conduct physical security assessments, and provide trainings on how to recognize and respond to potentially escalating situations,” Kim Wyman, senior election security adviser at the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, tells Mother Jones. The agency, housed under the Department of Homeland Security, held a national training on de-escalation techniques and released a companion video for those who couldn’t attend. Instead of pointing your finger, the video suggests keeping your hands “down, open, and visible at all times.” It warns that rapid breathing, clenched fists, and nervous laughter can be signs of imminent danger.

Not everyone is confident that’s enough. A March survey from the Brennan Center for Justice found that one-fifth of local election administrators were likely to leave their roles before 2024, many citing safety aspects. Meanwhile, an October survey from Reuters found that two-fifths of voters were worried about threats of violence or voter intimidation.

Wooten and his workers, therefore, would be forgiven if they had some pre-election jitters. They need only recall what happened after the 2020 vote, when Georgia’s secretary of state required a full manual tally of all votes cast in the presidential election. Wooten estimates some 150 people marched around the building they were working in, singing the hymn “Onward Christian Soldiers” while carrying Trump flags. “I kept thinking that the walls of the building would fall,” he says.

While the statewide audit ultimately showed no change in the outcome of the election, pro-Trump activists still attempted to badger Wooten’s workers.

Well, some of his workers.

As the team broke for lunch and headed for the parking lot where the election deniers were marching, “the white poll workers were told, ‘Enjoy your lunch,’” recalls Wooten, “and the Black workers were asked, ‘Were you still stealing votes?’”

It’s a tale as old as the nation itself. For over a century, agitators have attempted to interfere in fair elections, especially through attempted disenfranchisement of Black people.

While the United States ratified the 15th Amendment, enshrining Black mens’ right to vote, in 1870, it was far from a guarantee they could cast a ballot unscathed. In 1920, for example, a white mob repeatedly ordered Black men in Ocoee, Florida, to leave the voting precinct. When one Black man returned to the polls, a large group of white men—including members of the Ku Klux Klan—killed several Black men (historical accounts range somewhere between six and 60).

There was also the time in 1962, when poll watchers in Phoenix, Arizona—allegedly including one William Rehnquist, who later became a chief justice of the US Supreme Court—stood outside precincts asking Black voters to read an excerpt of the Constitution to prove their literacy, according to research cited in a 2021 report by the Texas Civil Rights Project.

In 1981, the Republican National Committee assembled an entity called the National Ballot Security Task Force in New Jersey. The group stationed armed, off-duty police officers and private security guards at predominantly Black polling locations and distributed literature that Democrats would later argue was voter intimidation. “WARNING,” read a poster created by the task force. “This area is being patrolled by the National Ballot Security Task Force. It is a crime to falsify a ballot.” As a result of these actions, the RNC signed a consent decree in 1982 requiring a federal court to review its future election security programs. That decree, however, was lifted by a judge in 2018.

Modern efforts to disenfranchise voters are sometimes less conspicuous. In Texas, for instance, a law passed in 2021 gives poll watchers “free movement” at precincts and makes it a criminal offense to obstruct their view. In Georgia, a new law allows any voter to challenge as many other voters’ registrations as they want.

“There’s more protections for covert racism within the polling place,” says Texas Civil Rights Project senior election protection attorney, Emily Eby. “This kind of sneaky, plausible-deniability intimidation is very much a way of the future.”

But independent groups have resorted to tactics far more reminiscent of the 1900s.

In Arizona’s Maricopa and Yavapai counties, voters have reported armed individuals guarding ballot drop boxes, and in some cases, photographing and threatening them. In Iowa, a man was recently arrested for allegedly threatening in voicemails to hang an Arizona election official.

And not unlike the 1980’s National Ballot Security Task Force, a group co-founded by former President Donald Trump’s national security adviser and avid election denier Michael Flynn is funding an organization attempting to recruit law enforcement officers and military veterans to become poll watchers, according to the Daily Beast.

“What we’re seeing is a far more organized and cohesive recruitment effort by election denier groups to gather poll watchers—official and unofficial—to monitor polls, and which results in intimidating voters,” says Jasleen Singh, counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice’s democracy program.

Users of far-right social media websites like Gab and Truth Social have also stated they plan to serve as official, party- or candidate-designated poll workers, according to a November 7 Politico report.

To be sure, official poll-watching, when done by the rules, can help protect trust in democracy by reassuring voters of election integrity. “There are plenty of poll watchers who stand peacefully in the polling place, observe the process, report any irregularities, and go about it without ever bothering any voters,” says Eby.

Actual harm done by these poll watchers to voters and poll workers at polling places is rare. “Generally speaking, the elections are going to run smoothly as they usually do,” says Singh. “The vast majority of voters in this country should be able to confidently go to the polls and cast their ballot.”

But when confrontations do happen, they can reveal just how entrenched election conspiracy theories have become.

Back in Chatham County, Wooten shares an example from Georgia’s May 2022 primaries. On the morning of the election, a poll worker turned on a touch screen voting machine and realized it had not been reset after accuracy testing was completed at the warehouse ahead of the election. In order to not risk accusations of malfeasance, the poll worker just boxed up the machine and planned to use the many other machines that were available. But a conservative poll watcher saw what happened, according to Wooten, and was “absolutely convinced” that the pre-election test votes on the machine were actually real votes that the election worker was trying to discard. “They raised hell,” says Chatham. “Nothing we said mattered.”

What the enraged poll watcher didn’t know was that the election worker they were so upset with was also a Republican.

“It wasn’t my business to say, ‘Look. He’s on your team’” Wooten says.