Content warning: This story contains descriptions of child sexual abuse.

The two girls at the sleepover huddled together on the bed, passing the cell phone around. They took turns glancing at the screen, fascinated and unsettled by what they saw but unable to look away. Their other friend wanted no part of what was going on.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Alauna, one of the girls on the bed, was intrigued. Olive-skinned, with blond hair and blue eyes, Alauna was slight for a 12-year-old. With the tap of a finger, she found herself video-chatting with a stranger. About a week later, it happened again at another sleepover, but this time, one of the other girls told her mom that her friends were “acting really weird” at the slumber party. She said Alauna stayed up all night talking to someone who “sounded like a man.”

After the first sleepover, Alauna became increasingly secretive and reclusive. She spent hours on her phone, disappearing into her room, and shielding her screen from her mother, Christal Martin. Finally, after hearing about the slumber party and the person who “sounded like a man,” Martin demanded to see her daughter’s phone. There were dozens of images and a video of her child, sometimes naked in provocative positions. Alauna had shared these images with up to 30 men, most of whom she’d met on a chat platform called Omegle.

The next morning, she put Alauna in the car and drove her to the police station in Green River, where they lived. Martin, now 37, was raised in this dusty, Wyoming, frontier town (population 12,000) with majestic buttes to the north and a Union Pacific railyard slicing through its middle.

The police took Martin’s report and Alauna’s phone. They asked Alauna a series of questions and opened an Internet Crimes Against Children investigation. Alauna was furious. She told her mother that she had sent photos to her friends, not to men. “She freaked out,” Martin says. “She was angry because I had taken away her phone, and how dare I take her away from her friends.”

That was in 2017. Looking back, Martin realizes that her anger at her daughter only exacerbated the problem. Alauna shut down. “She wouldn’t talk to me about anything,” Martin says. Never one to accept defeat, Alauna snuck into Martin’s bedroom, found an old cell phone, and got back on Omegle. After realizing this, “I just lost it,” Martin says. “You put your brothers in danger; you put this whole family in danger,” she screamed at Alauna. But Alauna had already warned one man that her mom had alerted the police and vowed to protect him. He was in his 30s or 40s; Alauna was still going through puberty. The man told her to call him “Master Daddy.”

Omegle is a website that pairs users at random for one-on-one video chats. “The internet is full of cool people,” the company boasts; “Omegle lets you meet them.” It was created by Leif K-Brooks in 2009 when he was 18 years old. (Chatroulette, a similar site based in Moscow, launched eight months later.)

But over the years, according to a lawsuit filed against Omegle, the “most regular and popular use” for the “cool people” on Omegle “is for live sexual activity, such as online masturbation.” For some men, semi-public masturbation is as far as it goes. Others use Omegle to persuade children to perform sex acts, expose them to porn, or even meet in real life, according to court documents. The men who use Omegle to sexually exploit children have been the subject of numerous federal investigations, and the company has been the target of a multimillion-dollar lawsuit, and a UN Special Rapporteur investigation.

Even so, many people over 30 have never heard of it; a lot of teens have, thanks in part to the pandemic. In January 2020, the site had 26 million monthly visits. Six months later, the New York Times ran a piece on Omegle’s popularity among teenagers stuck at home, and social media stars who started using the platform to keep a connection with their fans. The article also revealed the site’s dark side. “There’s the shock factor of it all,” an 18-year-old YouTuber named Nailea Devora told the Times. “There’s a lot of sexual porn stuff. We just film our reactions, like, ‘OMG I didn’t want to see that!’” By January 2021, according to the internet data firm Semrush, the site had 54 million monthly visits, due largely to Omegle users sharing videos of their more innocuous encounters to other apps. On TikTok alone, for example, videos tagged “Omegle” have racked up nearly 11 billion views.

There are two versions of Omegle. In the moderated version nudity and pornography are supposedly banned and the site periodically captures screenshots to scan for behavior that violates Omegle’s policies; the other version is unmoderated. Unlike Chatroulette, Omegle does not require users to provide any identifying information; it touts anonymity as an asset, to “help you stay safe.” And while its terms of service and community guidelines indicate that inappropriate behavior might be reported to the authorities, and Omegle does report many cases, the fine print is careful to indemnify Omegle. The TOS was updated on October 6 to declare the site is for adults only; until then, it welcomed kids 13 and up, provided they attested—by clicking on a button—that they had parental supervision.

Because it’s a private company, the true revenues are impossible to verify. Leif K-Brooks refused to answer my questions on how much money the company makes. According to a lawsuit against Omegle, the company’s revenue appears to come from selling user data and from ads, including for more overtly pornographic sites. A tab at the bottom of the screen of the unmoderated site, titled “Gay Cams,” redirects users to Chaturbate, while another, “Soft Moan,” leads to a webcam site called “Camegle,” offering categories like “Ass,” “Teen 18,” and “MILF.” It’s a synergistic relationship. On some adult streaming platforms, you can find videos depicting Omegle chats in splitscreen that show a man masturbating on one half of the screen while girls or young women watch in amusement, bewilderment, or horror on the other.

I first heard of Omegle one day last March, when I learned that the child of a close friend had gone on the site the previous summer, seeking respite from social isolation. That child, too, had met a man, “middle-aged at least,” who told them they were beautiful and sexy; then he asked them to do things for him—“sexual things.” They obliged, because if they didn’t, they said, they felt like they’d have been “stringing him along, abusing his kindness.” By December the child had attempted suicide, and in February they were placed in a psychiatric institution. Like Alauna, they were 12 years old.

They wanted to know if what happened to them counted as grooming and sexual abuse, and whether they should report it. They were still recovering emotionally from the ordeal, and said they were “doing bad, like really bad.” Their father and I affirmed that there was no question it was abuse, but we still didn’t fully grasp what Omegle was.

After speaking with the two of them, I went online to learn what I could about the site. I started by masking the camera on my laptop and going on the “moderated” version of Omegle, where I was immediately paired with a man masturbating beneath a blanket. I switched to the unmoderated version, where I clicked through five different chats and saw five erect penises. Because I could not see the users’ faces, it was impossible to know how old they were, but according to investigations of Omegle by the UN and the BBC, apparently prepubescent boys have been seen masturbating on the site.

I spent the next six months looking into the world of Omegle, a little-known company based far away from Silicon Valley and operated by a bit player you’ll probably never see giving testimony before the Senate. Because it operates in the shadows, Omegle is pernicious in different ways than the Big Tech companies we tend to associate with the spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories. But by acting as a conduit for child sexual exploitation, the damage it has enabled in individual lives is impossible to calculate. Nonetheless, if a couple dozen senators and a team of tenacious lawyers get their wish, Omegle and other sites like it could force the entire tech industry to change.

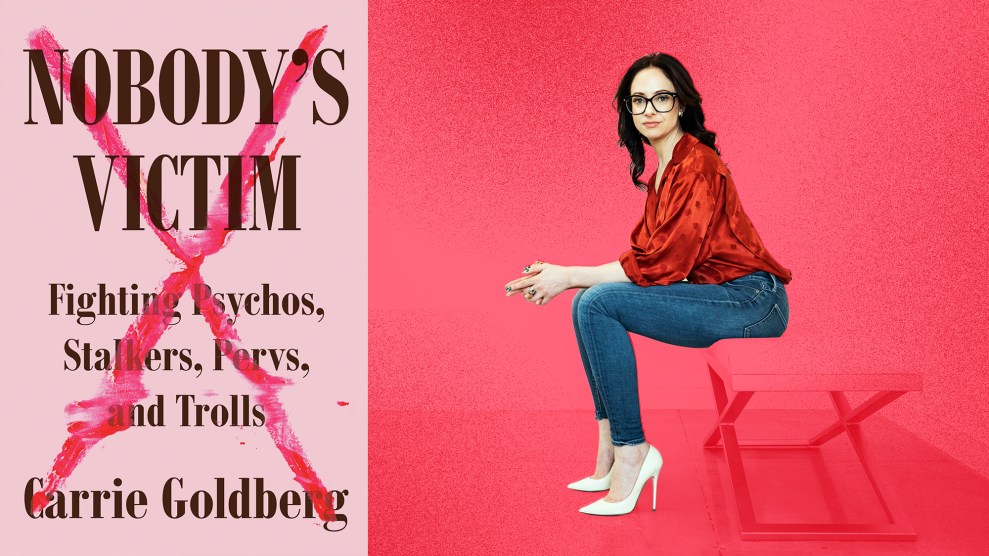

Predators who use the site have been prosecuted by law enforcement agencies the world over, but Omegle’s biggest foe may be Carrie Goldberg, a lawyer who, after being stalked and threatened with revenge porn, started her own firm in 2014 focused on representing targets of online abuse. In 2019, she published Nobody’s Victim: Fighting Psychos, Stalkers, Pervs, and Trolls, a book detailing her own experience as well as some of the more disturbing cases she’s worked on over the years. Raised in Aberdeen, Washington—home to Kurt Cobain—Goldberg was a rebellious teenager who, according to a 2016 New Yorker profile, made bras out of baby-doll heads and wrote erotica, which a teacher discovered one day after raiding her locker. Golberg was incensed that he’d invaded her privacy. A fellow Brooklyn Law School alum describes Goldberg as a “badass.”

In November 2021, Goldberg filed a $22 million lawsuit against Omegle on behalf of a 19-year-old woman from Michigan, identified as A.M., who was sexually exploited by a Canadian man she met on the site. According to court records, Ryan Scott Fordyce was randomly paired with A.M. on Omegle in 2014, when she was 11 and he was in his late 30s. Over a period of three years, Fordyce gradually coerced A.M. to take off her clothes and masturbate, recording whatever he demanded. He dispatched her to recruit other kids and threatened that if she told anyone, he would share her images publicly and she would get arrested.

In 2018, when investigators finally raided Fordyce’s home in Brandon, Manitoba, they found more than 3,000 files of sexually exploitive material featuring children on his devices—some involved bestiality and bondage—including 220 images and videos of A.M. Fordyce, who was married, claimed he thought his interactions with these children were consensual and didn’t know he was breaking the law. He’s now serving eight-and-a-half years in a Canadian prison, followed by 20 years of restricted release with no internet. A.M. eventually fled to New Zealand because, according to the lawsuit, “it was unbearable to be near the darkness of her adolescent and teen years.” She is triggered by the sound of a phone ringing because it reminds her of the day her parents received a phone call from the police after they’d found images of her on Fordyce’s devices. She no longer wears her hair to one side “because this was the Omegle Predator’s preference.”

Goldberg and her team spent the better part of three years building their case. For Goldberg, who speaks with breathless urgency, Omegle represents a broader problem with the tech industry: It’s an intrinsically flawed product that allows a small handful of people to profit off the exploitation of others while enjoying the full protection of the law. “This isn’t fucking free speech, you know, introducing strangers for the free exchange of ideas,” Goldberg says. “This is about criminal conduct.”

Goldberg says her firm isn’t interested in suing companies over specific content or even behavior conducted on their sites, but rather for creating products that enable sexual abuse by virtue of their design. For example, in 2017, Goldberg filed a lawsuit against the gay dating app Grindr for enabling a man to pose as his ex-boyfriend and solicit sex from strangers, who flocked to the ex’s home and workplace demanding sex. The lawsuit dragged on for more than two years and ultimately failed to hold Grindr accountable, but that only steeled Goldberg’s resolve. “We don’t give a shit about the content,” she says. “We’re not suing Omegle for anything A.M.’s abuser did or said to her. We’re suing them for the dangerous connecting [the platform] was doing, which is intrinsic to the product.”

This isn’t the first time Omegle has been sued. In 2020, the parents of an 11-year-old girl named C.H. sued the company for violating the federal Video Privacy Protection Act. In March 2021, the New Jersey judge hearing the suit ruled that “with deepest sympathy for the parents,” his court did not have jurisdiction over Omegle. The suit has since been transferred to a Florida court, where Omegle is based. Goldberg’s suit, meanwhile, is the first to take a product liability tack against Omegle, and she believes that if she wins, it will send a message to other tech companies that creating a product that facilitates sexual abuse can have significant financial consequences. But the best deterrent could be legislation that doesn’t allow another Omegle to crop up.

Even before Alauna became ensnared in Omegle, her short life had been marked by intergenerational trauma. Christal Martin and Alauna’s biological father, Don Fulkerson, separated when she was 2. Martin’s life had been tough. In 1993, when Martin was 8, her mother was abducted from the convenience store where she worked, raped repeatedly, and strangled to death. The police found her body 11 days later, buried in a snowdrift. Martin spent the rest of her childhood and teen years bouncing between institutions for troubled teens and foster homes. She eventually earned a GED, but still worked multiple jobs—waitress, bartender, office manager—to make ends meet.

In 2008, Martin met Wesley Brooks, who quickly became a second dad to Alauna, then 3 years old. In 2011, the new family moved to Midland, Texas, where Brooks had found work in the oil fields that surround the town. Alauna made friends easily in Midland, especially with a girl her age who lived on the same cul-de-sac. They played volleyball while their parents barbecued—a picture of middle-class stability. Then Wesley started working up to 110 hours a week and began using heroin and meth, which were rampant among oil workers. Martin tried to help him, but his addiction took over their lives. In October 2013, Martin took Alauna and her baby brother back to Wyoming.

The move was hard on Alauna. “For six years, this man was a constant presence,” Martin says, “somebody that she just absolutely adored.” Alauna and Brooks liked to sing together and go tubing in the lake. A year later, Brooks left a job site in Bowie, Texas, with his boss, Scott Allen Cambre. Cambre shot Brooks in the head and burned his body in a fire pit. Alauna overheard her mother talking about Brooks’ murder, learning all the grisly details. She was 9 years old.

Elizabeth Jeglic, Ph.D., an expert on grooming and child sexual abuse, says that trauma can put children at higher risk of sexual predation. “Oftentimes the reason kids are vulnerable is that they have some sort of psychological vulnerability,” Jeglic says. She says that children who identify as LGBTQ+ or marginalized ethnic groups, or who have disabilities, are statistically among the most at risk. Nonetheless, any child can be a victim. “It’s happening globally,” she says. “It’s across the board.”

Being back in Wyoming did bring Alauna closer to Fulkerson; she started dividing her time between her parents’ homes. But her life was fractured, and she missed Brooks. Around the time that Brooks was murdered, a younger kid introduced Alauna to online porn. By the time she discovered Omegle, in 2017, it provided the male attention she craved. It felt like love.

The trip to the police with her mother only emboldened Alauna. She continued her interactions with Master Daddy, who quickly moved their conversations off the site. He had configured his computer to change its IP address every few seconds, making him impossible to trace. He easily could have shared Alauna’s images on the dark web, or even the regular web. Even as Omegle has reported many instances of abuse, such strategies by predators make it nearly impossible to keep up. The Child Rescue Coalition reports that over 72 million IP addresses have shared or downloaded sexually explicit images and videos of children. Once such an image of a child is out there, it never goes away.

Wade Beardsley, an investigator with the Wisconsin Department of Justice, says that moving conversations off Omegle is standard procedure for sexual predators who use the platform to access children. “They’ll always try to switch them off [Omegle, etc.] and onto one where they know that they can communicate with the person in a much more reliable fashion,” he says.

Last year Beardsley helped to investigate a 35-year-old Wisconsin school teacher named McKenzie Johnson who, according to court records, used Omegle to contact a 13-year-old girl in Fontana, California. He soon moved their exchange of explicit material to email, which the girl’s mother intercepted and brought to the local authorities. They traced Johnson’s digital footprint to Wisconsin and a search warrant was issued. When Beardsley raided Johnson’s home, they found more than a thousand sexually exploitive images and recorded video streams, including one in which Johnson tells an 11-year-old girl to insert a Sharpie into her vagina and then instructs her on how to position her hand to give him a better view. In March, a judge sentenced Johnson to 20 years in federal prison followed by 20 years of supervised release.

Beardsley says that suspects are “always recording what the child is doing on the other end, and the suspect will hold that information over their heads.” Aware of this nefarious practice or not, other tech companies have stepped in to serve the market: A Google search for “Omegle video recording app” returns dozens of hits, some of which include easy how-to diagrams with screenshots of the Omegle interface. One of these apps, Bandicam, has been around almost as long as Omegle. (Bandicam says it has no direct affiliation with Omegle.)

Master Daddy was just one of the dozens of men Alauna met on Omegle, but he was notable for how aggressive he was. Martin says he’d yell at Alauna if she refused to call him Master Daddy. In contrast, the others seemed almost benign. Alauna, meanwhile, has largely blocked Master Daddy from memory. As Elizabeth Jeglic notes, “many of these [initial grooming] behaviors are similar to normal adult-child interactions.” This makes it hard for some moderation systems to catch until it’s too late. “Unless certain things are picked up, it doesn’t necessarily get flagged,” she says. “And [predators] are pretty smart, and they take these things offline pretty quickly. And once it’s offline, it’s very hard for whoever controls the server to detect it.”

Omegle has been able to exist for so long thanks to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. It essentially states that interactive computer services, like Facebook or Twitter, are not themselves publishers and are therefore not liable for what users post or do on those platforms. At the time it was drafted, Section 230 was heralded as a key feature protecting free speech when the rest of the CDA was considered by many to be a threat to open discourse online.

The CDA was written long before the age of social media, mass disinformation campaigns, social unrest fomented by lies of a stolen election, and of course, sites like Omegle. It’s now one of the most contentious issues in Congress, a lightning rod for debates over the boundaries of free speech. While Section 230 ostensibly excludes from protection any website that facilitates criminal conduct, Omegle claims it’s nothing more than a communications platform, as neutral as AT&T. “Omegle…operates against the backdrop of Section 230,” which “is widely recognized as playing a vital role in the free exchange of information and ideas on the internet,” declares Omegle’s fact sheet. For Carrie Goldberg, such a claim is laughable. “The difference [between Omegle and Facebook or Instagram] is that those platforms have some legitimate uses,” she says, echoing a claim she makes in her lawsuit. On Omegle, she continues, “a kid is, you know, going to be exposed to adult penises.”

In January, Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) sponsored a bill, titled the EARN IT Act of 2022, that would hold interactive internet platforms like Omegle—but also Facebook and even Gmail—liable for facilitating sex crimes against minors. With an almost equal number of Republican and Democratic co-sponsors, the EARN IT Act could rein in the entire tech industry—if it passes.

Not only would EARN IT limit the “liability protections of interactive service providers” with respect to child sexual exploitation, it would also require them “to report facts and circumstances sufficient to identify and locate” those involved in all reported claims, and increase “the amount of time that providers must preserve the contents of a report.”

Some prominent defenders of privacy and free speech, meanwhile, are fighting to stop the bill’s passage. An online petition warning that the EARN IT Act “threatens to destroy online encryption,” leading to “widespread censorship and crackdowns on marginalized communities,” has amassed more than 600,000 signatures. Joe Mullin, a policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that since 1990 has worked to protect privacy and innovation in the digital age, says the EARN IT Act is just a backdoor attempt to allow government agencies and private actors to scan our messages, photos, backups, and anything else we send or store online under the pretense of “protecting children.”

Mullin says that earlier rhetoric in Washington around overturning Section 230 focused on terrorism and, when that failed, politicians pivoted to child sexual abuse. Regardless of the stated mission, though, Mullin wrote in an EFF blog post, the act’s true goal is to create a “massive new surveillance system, run by private companies, that would roll back some of the most important privacy and security features in technology used by people around the globe.” He argues that criminals, and not the platforms they use, should be prosecuted for what they do on sites like Omegle, lest we all forfeit our right to privacy. “Having end-to-end encryption is not an invitation to criminals,” he told me. “It’s just a best practice for a private conversation.”

Prosecuting criminals, however, requires that we know a crime was committed, and the perpetrator’s identity. Omegle’s content moderation is spotty at best. “Omegle video chat is moderated but no moderation is perfect,” Omegle’s homepage states. “Users are solely responsible for their behavior while using Omegle.”

I told Mullin that having a law that protects Omegle seems tantamount to providing free masks to pedophiles who roam playgrounds for victims. He countered that he doesn’t see Section 230 as a loophole, but rather as something that aligns with “values that most people recognize—that if a harmful thing gets said in real life, then the responsibility should align with the individual who said it. We’re all responsible for our actions.”

Goldberg disagrees. She says that Section 230 was written with only third-party content, like text-based chat rooms, in mind, and not for “these complex, live video-chatting, sophisticated apps that have direct messaging and all this.” Goldberg also has little patience for the argument that Section 230 is necessary not so much to protect the Big Tech juggernauts like Facebook, but the “small babies” of the tech industry. “I’m like, fuck those small babies,” she says. “Omegle is a big, old, fat grandpa.”

In May, a district judge in Portland ruled that, in fact, Section 230 does not protect Omegle, allowing A.M.’s lawsuit to move forward. “What matters…is that the warnings or design of the product at issue led to the interaction between an eleven-year-old girl and a sexual predator in his late thirties,” the judge wrote. K-Brooks’ lawyers have filed another motion to dismiss the lawsuit, claiming that under Oregon’s product liability statute, Omegle is not, technically, a “product,” so the company can’t be sued for product liability. Goldberg’s team opposed the motion in September and is awaiting the court’s decision. Even if the court finds in favor of Omegle, Goldberg and her associate Naomi Leeds are not deterred. “We’ll say, fine, if you’re not a ‘product’ then whatever it is you’re designing, or manufacturing, is negligent—period,” Leeds says.

Alauna ran away from home when she was 14, two years after she first went on Omegle. For Martin and Alauna’s father, that was the last straw. They decided to send her to Meadowlark Academy, a facility for troubled adolescents in Cheyenne, 270 miles east. Alauna needed no convincing, telling her mother she wanted out of the house.

After six months, she was released on probationary status and enrolled in an alternative high school back home. In 2020, an 18-year-old boy blackmailed her into sending him nude selfies. When Alauna sought help from her guidance counselor, the counselor, per state requirements, called the police, who accused Alauna of distributing child pornography. Martin convinced them to leave Alauna alone because since she was only 15 she “cannot give consent.”

By the following year, Alauna was no longer on Omegle or sending nude selfies, but she was still struggling. She’d made some new friends, “kiddos that were, you know, a little jagged around the edges,” Martin says. She started inhaling air duster and tried overdosing on Benadryl. She dropped out of school and started interning at a spa. Martin sent her to live with her dad in Rock Springs for “a change of scenery.”

The internship gave Alauna a sense of direction: She’s now studying to be a massage therapist. She’ll be 18 in February, and “doing pretty good,” says Martin. The police report remains open, and if an image of Alauna surfaces during the investigation, the authorities potentially can prosecute the person who possesses it on her behalf. At this point, the likelihood of that happening is a matter of chance. Meanwhile, Martin has also confronted her own trauma. She’s embraced the restorative justice movement, meeting with, and forgiving, the men who killed her mother and Brooks. Alauna lives with her dad and calls her mom her best friend. She recognizes that she was a victim but isn’t going to let that define her life. “I got really lost into [Omegle]. I ended up forming a habit and hiding in my room and just being sort of locked off towards people,” Alauna told me. “But I’ve gotten better, that’s for sure.”

My friend’s child is also still grappling with what happened to them in the summer of 2021, on top of all the other challenges of being 13. Their father ultimately filed a police report, with their consent, and their case is now being investigated by the FBI. Both parents say that, in retrospect, their child’s depression began almost immediately after their encounter on Omegle. The child is glad I’m writing this article, though, and even read an early draft; they said it rings true with their experience and that they hope it will make a difference. Goldberg applauds anyone who comes forward, despite the shame and humiliation they might feel, “because really, they’re making this sacrifice to protect other people.”

Perhaps the most tragic part of this story is that none of it should be the least bit surprising. In April 2009, just one month after K-Brooks launched Omegle, the New York Times ran a short piece about the site, titled “Tired of Old Web Friends? A New Site Promises Strangers.” K-Brooks told the reporter, Douglas Quenqua, that he didn’t monitor the site at all. “As long as people are having fun, I’m happy,” he said. Meanwhile, Jason Tanz, a senior editor at Wired, told Quenqua that when he went on Omegle, the first person he was paired with suggested they have cybersex; the second was a 14-year-old boy in London. “It’s not hard to see how this is going to be a problem,” Tanz said.

A year after K-Brooks launched the site, his hometown newspaper, the Brattleboro Reformer, ran a feature about him titled “Whiz Kid.” In it K-Brooks, then 19, said that revenue from the site was helping put him through college. But even then, it wasn’t free of controversy. Just months after he’d launched Omegle, K-Brooks said, he’d gotten a call from the FBI about an Omegle user in Sweden who told another, in Finland, that they were planning to bring a gun to school on a particular date. The Finnish user contacted the Finnish authorities, who then contacted the authorities in Sweden, who contacted the FBI. K-Brooks said that he combed through logs for two weeks but found no red flags. “It took up a lot of my time,” he told the newspaper. He was focused on his computer science classes, he said, having built Omegle to be relatively self-sustaining and easy to use. “I don’t want to go around mucking it up and changing everything,” he said.

In 2016, he co-founded a new startup called Octane AI, which he has since left, that sells chatbots and data collection services to companies and celebrities, counting among its clients GoPro, Jason Derulo, Cardi B, and Aerosmith. In 2018, he was named to the Forbes 30 Under 30 list.

In 2021, following a BBC investigation into Omegle, human rights experts appointed by the United Nations issued an eight-page letter to Leif K-Brooks. In one two-hour period, the letter states, the networks’ investigators were connected at random with “12 men masturbating, eight naked males and seven porn adverts,” and that children were seen “engaging in sex acts.” The UN also shared this information with the governments of China, Mexico, India, the UK, and the US, and told K-Brooks that if he did not respond within 60 days the letter would be posted publicly and shared with the UN’s Human Rights Council. (The UN has not responded to Mother Jones’ inquiry about whether K-Brooks responded to the letter.)

When I first emailed K-Brooks, he replied that he’d be happy to get me whatever “additional information” I needed, but he wouldn’t agree to a phone interview. I asked him to comment on the fact that Omegle is being used by sexual predators to target and abuse children, but he demurred. “I, unfortunately, need to pass on this interview opportunity for now,” he wrote, “due to some open litigation matters.” In subsequent emails, K-Brooks sent me Omegle’s fact sheet, which emphasizes the safety of the site, but ignored many of my questions, particularly those regarding Omegle’s finances, its employees, and the substance of the UN’s letter—including whether he ever responded to it. And yet, he consistently thanked me “for reaching out” and concluded one of his more evasive responses with the line: “Please do not hesitate to be in touch if I can help with anything else.”

Goldberg says K-Brooks “probably didn’t set out to create a site where kids are being sexually exploited. But he did.” At one point, there was a warning on Omegle’s homepage that sexual predators have been known to use the platform to target their victims. Then the site took it down, and K-Brooks won’t say why. “If you create a product that facilitates child sexual abuse, then you immediately do everything you can to correct that,” Goldberg says. “If you can’t correct it, then you remove it from the market.”

Omegle has reported tens of thousands of incidents of online abuse to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and says it bans IP addresses flagged for illegal or inappropriate behavior, but the problem persists. In a sense, this just underscores the significance of Goldberg’s lawsuit and our collective willingness to simply look the other way. Caroline Knecht, a spokeswoman for Goldberg’s firm, likens A.M.’s case to what she calls “just one woman” syndrome: “A case may be heinous, but it’s viewed as a severe and isolated incident rather than the product of a machine built to facilitate it.” On Omegle, she adds, “abuse is not a bug, it’s a feature.” But this extends far beyond Omegle, opening up a whole new way of looking at the role tech platforms are playing in modern life, she says. “They are not some neutral receptacle.”

For now, Omegle still looks like it was built by an 18-year-old in 2009. Millions of people log onto the site every month. Master Daddy could still be among them, somewhere, looking for girls. Some will scream and giggle and close the site in fits of laughter. Others will stay and do whatever he says.